Hands are bait when grabbing giant catfish

June 20, 2002 — Forget about forethought — or any other type of thought, really — when you stick your hand in front of a 40-pound catfish, hoping that the monster mistakes your fingers for food. Thinking can only cause problems. It’s best to do such things with your brain on blank.

June 20, 2002 — Forget about forethought — or any other type of thought, really — when you stick your hand in front of a 40-pound catfish, hoping that the monster mistakes your fingers for food. Thinking can only cause problems. It’s best to do such things with your brain on blank.

So, when I first reached my hand into a wooden box occupied by a big, bad blue catfish, the only thing weighing on my mind was the muddy water of the Big Black River — and the words of Mississippi handgrabber Ricky Liles.

“You’ve got to get your hand in the fish’s mouth,” he said. “Because that’s the onlyest way you’re going to catch him.”

The folks I met the following day along the banks of the Ross Barnett Reservoir spillway outside of Jackson, Miss., would beg to differ. They were fishing for catfish the regular way, with rods and reels.

I told them about handgrabbing, and that I had tried it. When they were done eyeing me as if I was an escapee from the Mississippi State Insane Asylum, they offered their opinions:

• “Man, I’m not sticking my hand up in nothing in no water,” Cortez Green, 33, said. “I don’t care if there’s tons of fish in there.”

• “That’s why they made these,” said Kevin Primus, 35, pointing to his pole.

• “I know the Big Black. Alligators. Snakes,” said Ruth Usry, 56, shaking her head. “There’s alligators all in the Big Black. And water moccasins.”

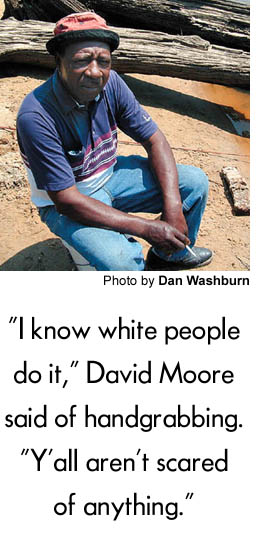

• “I know white people do it,” David Moore, 63, said. “Y’all aren’t scared of anything.”

• “I know white people do it,” David Moore, 63, said. “Y’all aren’t scared of anything.”

Handgrabbing is not for everybody. It’s an activity practiced by men many believe to be either half drunk or half crazy. But it’s also an activity that has been around for hundreds of years.

In 1775, trader-historian James Adair first documented “a surprising method of fishing under the edges of rocks” performed by American Indians in the South. Today, the idea is still the same. Handgrabbers have just perfected the process a bit.

Wooden boxes, dozens of them, lie on the bottoms of the Big Black River and Ross Barnett Reservoir. A large number of these custom-made catfish cabins come courtesy of Liles, Keith Lane, Gerald Moore and Mike Willoughby — the guys from mississippihandgrabbing.com.

The boxes, often made of durable cypress wood, are the size of coffins. They are placed flat on the river and reservoir floors. An opening, big enough for a giant catfish to fit through, is cut into the end of the box that faces downstream.

During spawning season, male and female catfish seek the shelter of the boxes — in pairs, of course. Once the female lays the eggs, the male chases her off and guards the eggs viciously until his fingerlings are hatched … or until some redneck reaches in the box and puts a halt to the whole process.

Many states, in fact, have banned handgrabbing, saying it’s not a sporting way to catch fish.

“I think the ones who say that,” said Liles, 43, of Canton, Miss., “is the ones, really honestly, who don’t have the nerve to do it.”

Liles and his crew contend that they raise far more catfish than they catch, saying that they purposefully leave several of their boxes untouched each season.

I asked Ron Garavelli, Mississippi’s chief of fisheries, for his thoughts on the matter. He’s been on the job for 27 years, and handgrabbing has been legal for all of them.

“Let’s just say I don’t think the catfish population is hurting because of handgrabbing,” said Garavelli, whose response to my next question — Are you a handgrabber? — came rather quickly. “No,” he said. “I’m not the type of person that puts my hands in places that I can’t see.”

Not many people are. If any species is at risk of endangerment, Garavelli said, it is the handgrabber.

“It’s a dying art,” Garavelli said. “I don’t think there will be a whole bunch left after this generation. You don’t see many young handgrabbers out there.”

When 56-year-old Gerald Moore was a “young ‘un” in Smith County, Miss., he handgrabbed on the Leaf River.

“Back then, we didn’t know about no damn box,” Moore said. “We’d find an old cypress log underwater. We done it for the food.”

And still today, Moore and his cadre of catfish wranglers do it as much for the food as for the fun. But, Moore will tell you emphatically, they “ain’t after the damn blue cat.”

And still today, Moore and his cadre of catfish wranglers do it as much for the food as for the fun. But, Moore will tell you emphatically, they “ain’t after the damn blue cat.”

“We’re after the flathead,” said Moore, who estimates that each season his group catches more than 3,000 pounds of flatheads, yielding more than 1,000 pounds of meat. “Because, as far as we’re concerned, the flathead is the best fish you can put in a frying pan. We don’t even keep the blues.”

Blue cats are harder to skin, and often even harder to swallow. Unlike the flathead, which prefers its meals to be on the move, blue cats often dine on the dead … or anything else that floats in front of its mouth.

“Your blue cat has got probably twice stronger jaws than a flathead, kindly like an alligator,” Liles said. “When they bite down on something, they can hold that grip.”

So, when you are submerged in several feet of water and a blue cat swallows your entire hand, you don’t have long to meditate on your next move. You’d be surprised how expendable extremities become when your only other option is drowning.

In one such situation, Liles — who, by the way, can’t even swim — remembers sitting at the bottom of the river, running out of air. His right arm was stuck halfway inside a blue cat in a box.

In desperation, Liles placed his feet on either side of the box’s opening, and with one powerful push, forced his hand out of the fish’s mouth — through the vise-like jaw and thousands of tiny teeth. Imagine running your knuckles against a cheese grater.

“You’re going to lose some skin,” Liles said. “But, hey, you’ve got to breathe.”

Using Lane’s mental map as our guide, we made our way back downstream and checked the sunken boxes in our path. The 55-year-old Lane — handgrabbing for 30 years — would wade, sometimes neck deep, through the swift water, holding a silver pole like a scepter. When he’d arrive at a box, he’d stick his feet and the pole into the opening.

Using Lane’s mental map as our guide, we made our way back downstream and checked the sunken boxes in our path. The 55-year-old Lane — handgrabbing for 30 years — would wade, sometimes neck deep, through the swift water, holding a silver pole like a scepter. When he’d arrive at a box, he’d stick his feet and the pole into the opening.

Sometimes the boxes were clean and empty, a sign that the catfish, in Moore’s words, had already “done spawned and gone.”

If a box is occupied, it’s often easy to tell. The catfish go crazy. They make their surroundings shake like a subway car.

“You can hear it underwater,” Liles said. “It sounds like thunder.”

At that point, the checker becomes the blocker and seals the opening with his feet until the grabber can get his gloves on.

Grabbing can be grueling. It is an often time-consuming task performed primarily underwater. And my companions were already short of breath from smoking cigarettes.

The grabber wedges his arm past the blocker’s legs and into the opening. (It’s best to stick your arm in up to the shoulder, so the fish trapped inside have no room to make a run for it.) Then, it’s a matter of poking around until you find something that feels like a fish head. Often, the fish head finds you.

Ideally, the fish bites down on your fingers and leaves your thumb alone. That way, you can grab on tightly to the cat’s lower lip. That’s when you’ve got him. Although, to be honest, it often felt like the fish had me.

It’s an odd feeling when a known predator puts its mouth on you. It’s a sensation that’s hard to put into sentences.

“Well, it’s … it’s, uh … well, I really don’t know how to describe it,” said Lane, of Waynesboro, Miss. “It’s just something biting you.”

If it’s a small fish — and in the world of handgrabbing, that means about 30 pounds or less — the grabber will pull it out of the box and come to the surface with the fish in a headlock.

For the big ones, the ones that would likely fight their way out of a simple wrestling hold, grabbers carry a brass spike attached to a long piece of rope. The spike goes through the fish’s lower lip and out its mouth. With the rope looped around the lip and wrapped around the grabber’s hand, escape is almost impossible.

“This is the golden rule,” warned nationally known outdoorsman and novice handgrabber Preston Pittman, who came along on our adventure to film footage for a new outdoors television show. “It’s a long walk home, if you let one get away.”

“This is the golden rule,” warned nationally known outdoorsman and novice handgrabber Preston Pittman, who came along on our adventure to film footage for a new outdoors television show. “It’s a long walk home, if you let one get away.”

The first nine boxes we checked that morning furnished us with four flatheads, including the 53-pounder Willoughby pulled out on our first stop of the day. Box No. 10, I would soon find out, had my name on it.

“Just stick your arm in there and see if you can feel him,” Lane said.

I took the plunge, but the cupboard was bare. Mr. Catfish was holed up in the far end of the box. That’s when Lane’s pole came into play. A couple pokes, and the catfish had changed its position.

“He’s up there now, over my foot,” Lane shouted. “He’s over my right foot right now.”

I went under again and felt the fish’s head right away. It was kind of like coming across a ripe melon at the grocery store. At that moment, I was thankful that the water was so muddy. I had no desire to stare into the mouth of whatever was now attached to my arm.

I was in relatively shallow water, so I could bring my head up for air. “I’ve got it,” I gasped.

Liles stuck his hand down to feel the fish. He paused, and then announced to the group gravely, “It’s a blue.”

Willoughby looked concerned, which didn’t help me much: This blue was biting my hand.

“Don’t have him string it if it’s a blue,” Willoughby said. “Just let him come out with it.”

I went under again, prepared to do my best Sergeant Slaughter impression and put the damn blue cat in a “death grip” like Moore told me to.

“Are you sure it’s a blue?” Lane asked Liles. There was so much worry in his voice, I likely would have polluted the river had I not been underwater when he said it.

“Are you sure it’s a blue?” Lane asked Liles. There was so much worry in his voice, I likely would have polluted the river had I not been underwater when he said it.

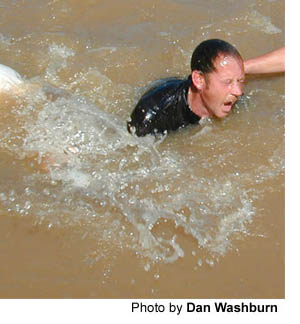

After a short underwater struggle, I shot out of the Big Black with a big blue in tow, my left arm wrapped tight around its repugnant mug.

Soon, I was laughing. And so was everyone else. I was accepted. I was part of the group. My rite of passage weighed 25 pounds and was still trying to eat my right hand.

“My man!” Willoughby exclaimed. “Got him a blue!”

Later on, another box had my name on it. It housed two flatheads, a male and a female who weren’t happy that I interrupted their party. The second, and larger one, bit me hard. I uttered some words that Pittman will have to edit out of his TV show.

Near the end of the afternoon, a man yelled to us from the only other boat we passed that day.

“How did y’all do?” he asked.

Moore remained poker-faced. We sat on coolers that contained 14 fish, a catch that weighed close to 350 pounds.

“Just some small ones,” Moore said. “Nothing big.”

As we drove off, Moore turned to me and cracked a sly smile. With the slime of a 30-pound flathead still glistening on my T-shirt, I smiled back.

I was finally in on the joke.