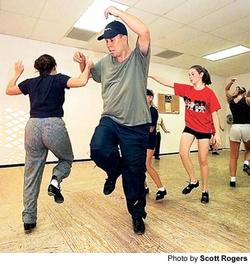

April 25, 2002 — Keith Brady’s feet went off like firecrackers. His knees were loose hinges — swinging back and forth, up and around. Everything below was a blur.

April 25, 2002 — Keith Brady’s feet went off like firecrackers. His knees were loose hinges — swinging back and forth, up and around. Everything below was a blur.

Perhaps Brady was a marionette, I thought. Perhaps someone, or something, was pulling at the strings from up above.

He made the unnatural appear natural. He made music with his feet. And then it was my turn.

“The good thing about clogging,” said Brady, 35, instructor at the Storm Dancers studio in Oakwood, “there’s no wrong step.”

Brady, obviously, hadn’t seen my steps yet.

Let’s get one thing straight. Clogging has nothing to do with wooden shoes or windmills. It’s a down-home dance, uniquely American.

But like most things born in Appalachia, clogging’s roots reach back across the Atlantic. A little Irish. A little Scottish. Throw in some English. Some German, too.

It was the 1700s, and all the different folk dances fused into one. Unchoreographed. Free-flowing. Much like the lives of the South’s early settlers.

“Clogging basically started as buck dancing,” Brady explained.

“Buck dancing?” I responded.

“Buck dancing is,” Brady began, “you go to a bar and see a bunch of guys that are, um, well lit. It has no structure to it. Just whatever they can stomp out.”

Clogging eventually found its way to the flatlands, where it met with other influences, Native American and African-American dance among them.

Clogging continues to evolve today.

“People are making up new steps all the time,” Brady said. “They take like half of an Irish step, half of a tap step and half of a Canadian step, put the three together and come up with something totally new.”

“People are making up new steps all the time,” Brady said. “They take like half of an Irish step, half of a tap step and half of a Canadian step, put the three together and come up with something totally new.”

Several years ago, Brady himself helped invent a step during a particularly productive early morning at a bar in Pigeon Forge, Tenn.

It’s called a “double-double.” It sounds like a musical machine gun. And, I quickly realized, there was no way I was going to come close to accomplishing it.

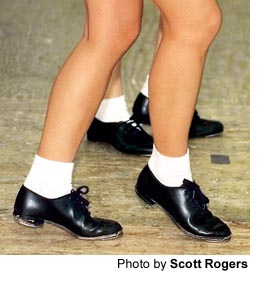

Clogging draws its name from the Gaelic word for “time.” And the clog dancer, wearing shoes very similar to those worn in tap, is supposed to hit the floor on the downbeat.

I was just plain offbeat.

Brady and I were trying to boogie to the Doobie Brothers’ “Steamer Lane Breakdown,” and I stopped in mid-song. It just didn’t feel right.

“That’s one good thing about him,” Brady said to the growing crowd at the studio (the presence of which likely played a factor in my faulty footwork). “He knows when he’s not on beat.”

Brady hasn’t had that problem in some time. A Hall County native, Brady’s family moved to Arcade when he was a young boy. When Brady was 12, he attended a clogging class at the town hall. He hasn’t stopped stomping since.

“It was the thing to do,” Brady said — and for anyone who has ever driven through Arcade on the way to Athens, that statement is easy to believe. “It was the only thing you had to do in a little town.”

By the mid-1980s, Brady, who performed locally with a group known as the Foot Stompin’ Heel Clickers, was the best clogger in the world. Five years straight, he beat out 1,500 competitors to win the “Hee Haw” world championship at the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville, Tenn.

Now he spends his time teaching. At Storm Dancers, he has around 70 students from age 4 to 60. And they clog to anything from bluegrass to country to rock to hip-hop and pop.

“We do routines to all of it,” said Brady, a land surveyor when he’s not clogging. “When you start clogging to Britney Spears, that’s when all the little girls come running saying, ‘I want to dance like that.'”

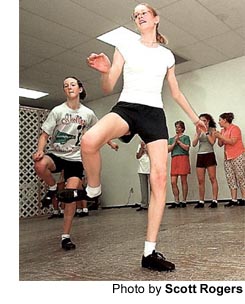

Thirteen-year-old clogger Taylor Soucie, an eighth-grader at West Hall Middle, remembers catching her first glimpse of clogging at the age of 5.

Thirteen-year-old clogger Taylor Soucie, an eighth-grader at West Hall Middle, remembers catching her first glimpse of clogging at the age of 5.

“It was fast,” Soucie said. “I thought it was cool.”

Kristi Pirkle, 16, who like Soucie is on Brady’s performance squad, has been clogging for nearly two-thirds of her life.

“I don’t play sports,” the West Hall High junior said, “but I thought this was interesting. And it’s good exercise.”

Brady claims that 15 minutes of clogging is equal to seven miles of running. And if I had been able to last 15 minutes, I’d be able to tell you if he’s telling the truth. You’ll have to take Brady’s word on this one.

I started out strong. I ended up shaky. The more steps Brady taught me, the less I felt I learned.

“I’m thinking too much,” I said after realizing I had been sticking out my tongue in contemplation for the lesson’s duration.

“Yep,” Brady said. “You’ve got to relax and go with it. You can’t think about it a lot.”

I watched Brady’s top class practice. I watched them relax and release. With the most experienced cloggers, it’s as if the beat moves the body, not the other way around.

I liked it best when the music was off and the sound of shoes filled the room like a symphonic factory. Everyone was in step.

The worn wooden floor sagged with each collective stomp.