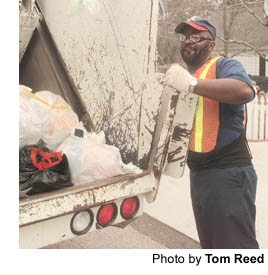

April 21, 2002 — When Gainesville solid waste superintendent Adrian Niles explained it, the job description seemed simple enough. Get garbage out of can. Put lid back on can. Carry garbage to truck and throw it in the back.

April 21, 2002 — When Gainesville solid waste superintendent Adrian Niles explained it, the job description seemed simple enough. Get garbage out of can. Put lid back on can. Carry garbage to truck and throw it in the back.

Repeat, again and again.

So that’s what I did. For one day, I was a Gainesville garbage collector. And, you know, it wasn’t as bad as you might think.

Sure, it smelled a bit, and I soiled a pair of slacks. But at the end of the day, I knew my body had been through a day’s work. Real work. Sweat work.

We white collar types tend to forget what that feels like.

“It’s a good, honest paycheck,” 50-year-old Frank Hood, a garbage collector for two decades, said to me as we sat in the lounge of the public works building on Alta Vista Road in the minutes leading up to the 7:30 a.m. start of our work day.

Hood reminded me to wear my gloves — it’s easy to get stuck by syringes or broken glass — and recommended that I carry along eye protection, too. He closed with a statement that took me by surprise: “It’s fun. It really is.”

Hood continued, “You meet a lot of different people out there. People who stay in a lot, they miss it all. When you’re out there, you know what’s going on.”

Want to learn a little about your neighborhood? Ask your garbage collectors. You can learn a lot about people by carrying their trash.

Just judging by the size — and the smell — of the load you can determine someone’s age, someone’s eating habits. Garbage men know when new babies arrive (dirty diapers are a dead giveaway) and when children head off to college (the load becomes a lot lighter).

Just judging by the size — and the smell — of the load you can determine someone’s age, someone’s eating habits. Garbage men know when new babies arrive (dirty diapers are a dead giveaway) and when children head off to college (the load becomes a lot lighter).

Garbage men know when families move away and when others move in. And they take special notice of any new dogs in the neighborhood. You see, dogs don’t differentiate much between the people who pick up the trash and the people who deliver the mail. They don’t like either one.

Gainesville is a city that doesn’t appear to have been laid out in any particular pattern. Streets criss and cross at odd angles. A single road can be known by several different names.

But it all makes sense in the minds of the garbage men. They drive these streets every day.

It’s not just the streets, either. If you live in Gainesville, Richard Trammell, the driver of the truck that I worked on, likely knows where you hide your trash.

“I know where all the hot spots are,” Trammell, 45, said with a chuckle.

Gainesville residents aren’t asked to bring their trash to the curb. They aren’t even asked to bring it to the front of the house. Garbage collectors are expected to collect the garbage from wherever it is kept.

And that could be behind a big tree in the backyard or behind a fence next to the garage.

The level of service shocked Dick Young when he moved to Gainesville from Dekalb County last year. He made a point to say hello to Trammell and my truck’s other “toter” Darrell Carter when we pulled up next to his house.

“These guys are great,” Young, 67, said. “They are so helpful, too. I never heard them complain, and that’s unusual. I wouldn’t mind having to bring the trash up myself. I would do it if it came to that. But for them to go around back and pull it out, I think that’s terrific.”

It’s a nice service. I agree. But after eight hours of tramping up driveways and through backyards in search of trash, my aching legs had a different opinion.

The average Gainesville garbage collector — of whom there are 20, responsible for nearly 5,000 city residences — walks six miles a day.

“It’s just go, go, go,” Niles said. “It keeps 20 busy. It’s stop and go. It’s uphill and downhill. It’s hopping off the truck and hopping back on.”

Some guys don’t even make it through the first day. It’s too hard, too smelly, too messy. They radio back to the office and ask to be picked up by the side of the road.

“Even with a garbage toter, it takes a special kind of person that wants to do this work,” Niles said. “You would think anybody could do it, but it does take a special kind of person.”

Riding on the back of a garbage truck is strangely liberating. Lean back a bit and the wind hits you in your face. It makes you feel like you’re flying — and neutralizes some of the truck’s odor.

I also found pleasure in operating “the blade,” the mechanical door that sweeps the trash inside the truck. In a matter of minutes, an overflowing load vanishes. All that is left is a foul soup — milk, grease, blood and other liquids and juices whose expiration dates have come and gone. The vile brew drips down the blade and settles in a big black puddle.

I also found pleasure in operating “the blade,” the mechanical door that sweeps the trash inside the truck. In a matter of minutes, an overflowing load vanishes. All that is left is a foul soup — milk, grease, blood and other liquids and juices whose expiration dates have come and gone. The vile brew drips down the blade and settles in a big black puddle.

Oh, and then there’s the smell. There’s always the smell.

Trammell, Carter and I eventually settled into a rhythm.

“We’ve got to go get it,” said Carter, 34, toting for a little more than a year. “No matter what, rain or snow, we got to go get it. It’s our job. That’s how we look at it. We work as a team to get this thing done.”

When Trammell would stop the truck, I’d look to his face in the side-view mirror. A nod meant it was my turn.

“Go to that white house,” Trammell said on one of our early stops. “It’s going to be around back. He’s got some white bags on his patio.”

Sure enough, Trammell was right. And the old man who keeps white bags of trash on his patio was smoking an early-morning cigarette on his screened-in back porch.

“You’re a new guy, ain’t you?” he said to me.

“Yep,” I responded. “It’s my first day.”

“Well, hang in there. You can retire in about 80 years.” The old man laughed.

True, the job of garbage collector is not one people usually plan for themselves. It just kind of happens.

Garbage toters in Gainesville start out at $7.69 an hour. But there’s room for advancement. Trammell has been doing it for 21 years, and he’s moved from the back of the truck to the driver’s seat.

“You would think that out of all the other jobs I had, that they would have been better for me than doing this here,” Trammell said. “It’s one of the worst jobs in the world, I guess, and I done stuck with it this long. It does have good benefits, though. That’s one thing that kept me here this long. And the hours are really good.”

We took our only break of the day at mid-morning. By that time, the gloves I wore were no longer white. We sat on the curb at a gas station and ate a snack. The break didn’t last long.

Streets and houses ran together as the day wore on. It all started to look the same to me.

Streets and houses ran together as the day wore on. It all started to look the same to me.

Get garbage out of can. Put lid back on can. Carry garbage to truck and throw it in the back. Repeat, again and again.

Sometimes the monotony is broken. Perhaps you come upon a dead dog covered in maggots — yep, some people throw those out with the trash — or an appliance that is still in working condition.

Trammell remembers one time when a homeless man emerged from a Dumpster that was about to be emptied into the truck.

“We almost killed him,” Trammell said.

Garbage men are blue-collar magicians. They make things disappear. We often bag up our trash, put it outside and then forget about it. It goes away twice a week. We take it for granted.

“Sometimes a customer will tell me I’m doing a good job,” Carter said. “And I take that and say to myself, ‘It’s going to be all right.'”

I was worried that I might slow Trammell and Carter down, but we made good time. We finished our route and made it back to “the house” with minutes to spare.

“You’re garbage man material,” Carter said to me with a wide smile. “If you can hang for the day, you’re garbage man material.”

I took it as a compliment.