July 31, 2001 — Tallulah Gorge sucked me in. It swallowed me whole.

Inside this 1,000-foot crack in the Earth, I discovered a world far removed from the four-lane federal highway that hums along the canyon’s rim.

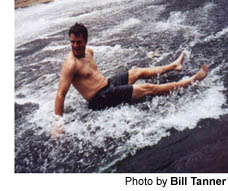

It’s a world where water flows freely — sometimes with the force of a giant fire hose — and falls frequently — often several dozen feet at a time. It’s a world where rock climbers cling to gorge walls like spiders on a web, where children (young and old) slide down Bridal Veil Falls like visitors at an amusement park.

It’s a world shared by snakes, salamanders and, yes, sports writers. We slither, scurry and skip along the same river of rocks. To onlookers up above, we’re all just specks on a slab of stone.

It’s a world shared by snakes, salamanders and, yes, sports writers. We slither, scurry and skip along the same river of rocks. To onlookers up above, we’re all just specks on a slab of stone.

A hike along the gorge floor provides perspective. Down there, all living creatures are equal. The raging water and walls of rock rule all.

“I actually have a healthy fear of heights,” Bill Tanner admitted as we peered down toward the Tallulah River from one of several overlooks positioned around the chasm.

Such a fear could be considered rather unhealthy, actually. Especially for a man in Tanner’s hiking boots. He is the park manager at Tallulah Gorge State Park, which houses one of the deepest gorges east of the Mississippi River.

We didn’t stand on the edge of the gorge for long. Soon we were descending the 595-step staircase that leads to Hurricane Falls, the 96-foot wall of whitewater that served as starting point for our five hours on the floor.

“Are your shoes sticking good?” Tanner, 41, asked me as we stood on dry rocks, the river rushing around us. “If your boots stick on the rocks, you’ll have a great day.”

Tanner speaks from experience. He is the only park manager Tallulah Gorge has known since it became a state park in 1993. The 3,000 acres that include the 2-mile canyon are a public/private partnership between the Georgia Department of Natural Resources and the Georgia Power Co., which operates the hydroelectric dam on the west end of the gorge.

The dam, constructed in 1912, created the 63-acre Tallulah Lake and drastically decreased Tallulah River’s water flow. Reduced to whatever water managed to leak over the dam, the river gurgled through the gorge at less than 15 cubic feet per second (cfs) — which isn’t much at all.

Now, thanks to the DNR/Georgia Power partnership, water flows normally at about 50 cfs. During several days of the year, the park features aesthetic water releases of 200 cfs. And for five weekends each year — the first two in April and the first three in November — the gods of whitewater paddling smile on Tallulah Gorge.

The gorge gushes on those days. Water is released at 500 and 700 cfs.

Crack kayakers and canoeists from across the country apply in writing for a shot at shooting the gorge. There is a waiting list. Only 120 paddling permits are granted each release weekend.

“You used to be able to hike the gorge floor and not get wet,” Tanner said. “That’s not true now.”

There are no trails inside Tallulah Gorge. Just rocks and a sliver of shoreline. Hikers find their way by trial and error.

We hiked from the stairs at Hurricane Falls to the trail at Bridal Veil Falls, more commonly known as Sliding Rock. Not sure what mileage we covered, but distances don’t matter down where we were. Let’s just say it was a three-waterfall walk.

This is a route Tanner has hiked often over the years, probably 1,000 times or more. It’s called “gorge patrol.” So I listened to what he said, and mimicked his every move.

“You can imagine being a little boy again, hopping from rock to rock,” Tanner said. “It’s tough, but folks love it. I love being paid to be down here.”

The gorge houses six endangered species of plants and animals (one flower, the Persistent Trillium, is found nowhere else in the world). It also houses at least one dangerous species. Tanner knew right where to look.

“Oh yeah, he’s there,” Tanner said, down on all fours, peering under a narrow rock ledge within earshot of Hurricane Falls. He stood up rather quickly.

I hunkered down for a look. A copperhead snake was coiled in the shade. It was small, but it was still poisonous. We spotted a couple of other snakes during the day. Poisonous? Not sure.

There are two main ways to tell a venomous snake from a non-venomous one. Pupils and pits. Poisonous snakes have elliptical pupils, not round ones. They also have an indentation, or pit, located just behind the nostrils.

But either way, Tanner said, if you’re in a position to examine these features on a snake in the wild, “You’re too dadgum close.” We continued downstream.

Occasionally, I’d have to step around a big old bolt screwed into the stone. They were rusty reminders of Karl Wallenda’s 1970 high-wire walk across the gorge. The 65-year-old circus acrobat became the second person to accomplish the feat (tightrope walker Professor Leon did it in 1886) and nearly 300 journalists and 35,000 spectators were there to watch.

Occasionally, I’d have to step around a big old bolt screwed into the stone. They were rusty reminders of Karl Wallenda’s 1970 high-wire walk across the gorge. The 65-year-old circus acrobat became the second person to accomplish the feat (tightrope walker Professor Leon did it in 1886) and nearly 300 journalists and 35,000 spectators were there to watch.

Then in 1971, scenes from the movie “Deliverance” — including actor Jon Voight’s famous ascent up a cliff wall — were filmed in Tallulah Gorge.

That was the most national attention the area had received since the early 1900s, when the town of Tallulah Falls was one of the most popular resorts this side of the Mason-Dixon line. It even earned the moniker “Niagara of the South.”

Grainy black-and-white photos from these bygone days are displayed at the park’s 16,000-square-foot Jane Hurt Yarn Interpretive Center. I saw them after I sweated my way out of the gorge, up the steep and stony Sliding Rock Trail. And I stared at them in disbelief.

Regular folks, dozens of them, stand on the gorge floor. The men wear suits, the women large hoop dresses and high heels. No one has hiking boots on. How did they get down there? I scanned the photo’s caption for an explanation. Nothing.

Even Tanner didn’t have the answer.

“I’ve asked that very question many times,” he said.

By the beginning of the Great Depression, those well-dressed vacationers were gone. The expansion of the Tallulah Falls Railway, the damming of the Tallulah River and a devastating fire that burned the town down in 1921 all contributed to the end of the region’s grand Victorian era.

But now a new heyday is here. I heard it just around the bend.

Tanner turned to me and said with a smile: “The sounds of Sliding Rock.”

The clamor could just as well have come from Lake Lanier Islands. And, in many ways, that’s what Sliding Rock is. It’s got the water. It’s got the ride — a gradual slope of slippery stone. And plenty of people eager for a thrill.

Most of the danger involved actually comes before and after the slide. It’s darn near impossible to walk on wet rock — or dry rock with wet feet — without looking like an idiot or, worse yet, falling.

Such slips, in one way or another, are responsible for most of the mishaps inside the gorge. And Tanner rattled off recollections of gorge accidents like old war stories. Falls, drownings and deaths. Fractures, traumas and lots of injuries.

In the park’s first 18 months, there were six fatalities and at least 50 “really bad” accidents. But in the seven years since the permit system was established — only 100 people are allowed inside the gorge per day — there have been no deaths, and the injury rate has dropped dramatically, so much that Tanner fears he may be a bit rusty in his rescue training.

The key to the drop in injuries? Cracking down on the two main causes: “Booze and dope.” Tanner said the phrase again and again. He said it quickly, often tying the words together. Booze-and-dope. Boozandope. Sounds like the name of a summer concert festival.

Before I took my turn on Sliding Rock (several turns, actually), Tanner and I hiked just around the corner to Horseshoe Bend, a colossal curve of quartz that is sometimes called “the amphitheater.”

Before I took my turn on Sliding Rock (several turns, actually), Tanner and I hiked just around the corner to Horseshoe Bend, a colossal curve of quartz that is sometimes called “the amphitheater.”

“This is just a bizarre geographic feature,” Tanner mused.

If not for the rumble of rapids through the turn, we likely would have heard the highway hum of U.S. 441.

“That’s the neat part about it,” Tanner said. “You’re down here feeling that you’re really away from everything. And I guess you are, in a way.”

Back at Sliding Rock, Oakwood resident Mary Mills and her daughter Julie were slip-sliding away.

Fifty-one-year-old Mary had never been inside the gorge, even though she’s spent most of her life in Hall County, less than an hour’s drive from the park. It’s a simple, straight shot up I-985/Ga. 365/U.S. 23/U.S. 441 … whatever you want to call it.

Mary and 18-year-old Julie, a recent North Hall High graduate, slid down the falls again and again.

“It’s wonderful,” said Mary, a teacher at Flowery Branch Elementary. “I called my husband from down there just to tell him how neat it was.”

Added Julie, “It’s cool. Just to look up and see nothing but rock walls on both sides. You’re really down in it.”

After I slid my share, had my fill of fun, it was time to get back to “work.”

“Where are the best spots to take photographs?” I asked.

Tanner chuckled and scanned our surroundings.

“Anywhere.”

Tallulah Gorge State Park

• Getting there: From Gainesville, take I-985/Ga. 365 north to U.S. 441 north into Tallulah Falls. Follow signs to Jane Hurt Yarn Interpretive Center.

• Hours: 8 a.m.-dark (park office 8 a.m.-5 p.m.)

• Fees: Parking, $2-4 per day or $25 per year (Wednesday is free); Camping, $12 for tent, $14 for trailer/RV

• Highlights: 3,000-acre state park was created through a partnership between the Georgia Department of Natural Resources and Georgia Power Co. The gorge, one of the deepest in the eastern U.S., is 2 miles long and drops nearly 1,000 feet.

• Facilities: More than 20 miles of trails; 50 tent/trailer/RV sites; two lighted tennis courts; 63-acre lake with beach; picnic area and shelter; 16,000-square-foot interpretive center

• Activities: Hiking, camping, swimming, tennis, picnicking, hunting, fishing, mountain biking, rock climbing, whitewater paddling (restricted to first two April weekends and first three November weekends)

• Permits: Required for gorge floor access, rock climbing, whitewater paddling and certain hiking, biking and backcountry camping trails. Call park office for details. Notice: permits are limited and go quickly.

• Contacts: Park office, (706) 754-7970; Reservations, (706) 754-7979; Web site, www.gastateparks.org; E-mail, tallulah@alltel.net