July 17, 2001 — Betty Jakes felt she was going to be sick. I know this because she said so, probably not knowing that my tape recorder — recording away — was sitting right beside her.

I was out of earshot, perilously perched on the back of Jake’s horse, the Duchess of York. Fergie and I had just come very close to running over a nice lady holding a camera. This was before we had even thought about attempting any jumps.

The display was enough to make someone sick. Especially the owner of the horse.

“Is everything OK?” asked Peter Atkins, instructor for this lesson in “eventing” — perhaps the most dangerous, and easily one of the more obscure Olympic sports around. “You might want to go read that sign now.”

I gradually guided Fergie over to the other side of the barn, where we came upon a white sign posted on a wooden fence. It looked something like this:

Five minutes later, Fergie sent me flying. I’ll get to that eventually.

Some liken eventing to an equestrian triathlon. Developed from drills used to test cavalry horses in Europe, the three-day event includes the riding disciplines of dressage and show jumping. But it is the cross-country, or endurance, phase that attracts athletes and spectators alike. It is spectacular. It is severe.

Each team, horse and rider, must negotiate an intricate course several miles long that features dozens of immovable, and seemingly implausible, obstacles — all the while maintaining a pace of better than 20 mph.

I got my first taste of eventing back in May at the Foxhall Cup in Douglasville. Jefferson resident Cindy Phillips, chief steward of the cross-country obstacles, carted me around from jump to jump during the competition. And I was blown away.

Few sports are more beautiful. Few sports are more bewildering.

The obstacles are ingenious: Rube Goldberg-like creations, with steep rises and sharp falls, water hazards and trenches. The jumps are solid objects, often made of stone or wood, with little or no give. They can stand several feet tall. At Foxhall, one of the obstacles was a brand new Bentley automobile.

The horses approached each jump like muscle-bound steam locomotives. Breaths billowed out of large flared nostrils. Hooves hammered turf: ba da dum! ba da dum! The noises built to a crescendo that made me cringe.

The horses approached each jump like muscle-bound steam locomotives. Breaths billowed out of large flared nostrils. Hooves hammered turf: ba da dum! ba da dum! The noises built to a crescendo that made me cringe.

The prospect of these 1,000-pound creatures clearing such encumbrances was preposterous to me. But they would — most of the time — and all I could do was smile, and shake my head in astonishment. There were times, however, when jumps went unjumped, and horse and rider came crashing to the ground.

Sometimes they don’t get up.

Atkins and his top horse could have easily died in a fall earlier this year. But the 36-year-old was lucky to walk away with just a dislocated shoulder — the first major injury of his career — and his horse escaped with minor bumps and bruises. Eventing’s inherent hazards, Atkins said, are always on his mind heading into a jump.

“You’re worried. You’re scared,” the native of Tasmania, Australia, told me during a break in his clinic Saturday at Starlight Farm in Dacula. “If you’re not, like any dangerous sport, you are stupid. But it’s exhilarating. The speed and the power that’s underneath you. It’s like driving a really high-powered sports car.”

Eventing can be dangerous, to be sure. Just ask Christopher Reeve. Just ask anyone who competes in the sport.

“I’ve lost five really good friends in the last four years,” said Atkins, who competes throughout the world. “But it’s what you love.”

During the cross-country phase, riders must wear flak jackets, helmets and medical arm bands. The sport is often said to be as dangerous as stock-car racing, perhaps even more so. Atkins often made the analogy. He spoke with admiration of the late Dale Earnhardt who, Atkins said, died doing what he loved.

“When I die,” Atkins added, “I’d like to die off a horse.”

Not sure if Atkins’ students feel quiet as strongly about the subject as he does — I know at least one who doesn’t — but they all have two things in common. They love horses. And they are just a little bit crazy.

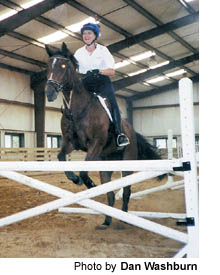

Phillips was on hand Saturday, as well. And the 35-year-old smiled and giggled after she and her horse completed each jump. As Atkins raised the jumps higher and higher, Phillips’ smile got bigger and bigger.

Phillips was on hand Saturday, as well. And the 35-year-old smiled and giggled after she and her horse completed each jump. As Atkins raised the jumps higher and higher, Phillips’ smile got bigger and bigger.

“It’s just a huge high,” said Phillips, eventing for seven years now. “It’s kind of like flying, in a way.”

Jakes got chills when I asked her to describe the highest jump of her life.

“It was like a Six Flags ride,” the 53-year-old Oxford resident said. “It was the most exciting, exhilarating thing I’ve done in my life. It scared me to death.”

So too, I believe, did the sight of me on the back of her horse, Fergie. Good thing for Jakes I didn’t stay there for long.

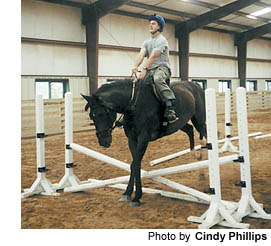

The jumps Fergie and I went through were short. Very short. Maybe a foot tall. Likely less.

But that didn’t matter. They still made my body freeze in fear. They still made me hold onto Fergie for dear life once her hooves returned to earth.

Having such a mass of muscle beneath you is daunting. The power is unmistakable. I was never in control.

Having such a mass of muscle beneath you is daunting. The power is unmistakable. I was never in control.

At no time was that more apparent than after my third — and final — jump. That’s when Fergie sent me flying. I somehow managed to land on my feet.

“Nice flying dismount!” someone offered from the crowd.

“Yeah, but it’s horse riding,” Atkins added. “This isn’t a rodeo.”

“Have you had enough?” Phillips asked me.

I’m pretty sure Fergie had enough. And I’m certain Jakes had more than enough.

“I think I’ll quit while I’m only a little bit behind,” I replied.

“Behind?” Atkins interjected. “You’re ahead.

“You don’t have any broken legs yet.”