| Michael Crowder of Gainesville, Ga. scales a cliff in Tallulah Gorge State Park, the only state park in Georgia to allow rock climbing. |

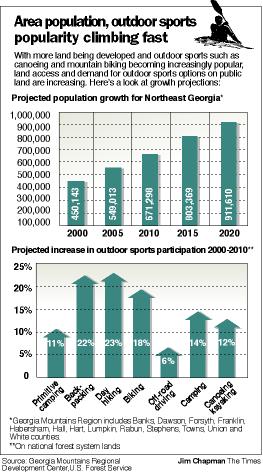

| Access denied: Owners, users spar over land | By Dan Washburn The Times Rivers. Mountains. Lakes. North Georgia's wide open spaces are attracting more outdoors enthusiasts each year. But those wide open spaces — and the public's access to them — are quickly fading away. Development and demand are seeing to that. The Georgia Mountains Regional Development Center projects the population of its 13 counties — 450,143 in 1999 — to more than double to 911,610 by 2020. Couple that with the 64 percent increase nationally in outdoor recreation the U.S. Forest Service expects over the next 45 years, a trend mirrored in this region, and the conflict becomes clear. More people. Less open land.

Two intrinsically American values — the inalienable rights of private

landowners and the natural rights of people to recreate on public land — are clashing. "It's a huge issue now and it will grow," said Risa Shimoda Callaway, a director of American Whitewater, a national nonprofit organization dedicated to conservation and access issues. "As people become more mobile, as people have more resources to travel, as people are more aware of enjoying natural resources that are out of urban and suburban areas, and as contractors, developers and private citizens continue to purchase and develop land, access becomes an issue." The conflict in North Georgia is a confusing amalgam of the old and the new, of state and federal laws, of mountains and streams. Its cast of characters includes landowners and land managers, bureaucrats and businessmen, environmentalists and adventure seekers — and lawyers, plenty of lawyers. And much of it involves a splitting of legal and philosophical hairs that would make Mother Nature and Uncle Sam cringe. Nowhere has this tug-of-war played out more dramatically than on Georgia's rivers and streams, where the dispute over what is public and what is private is as murky as the Chattahoochee River after a hard rain.

The answer depends on whom you ask. Fred Lovell doesn't allow people to paddle or float down the two-mile stretch of the Soquee River that flows through his land in Habersham County. "I don't claim I own the water," Lovell said. "But if I didn't own the bottom of the river, the water wouldn't run through it. God Almighty I'd say probably may own the water. But while it's on me, I feel like it's mine." Georgia law says the owner of land on both sides of a "non-navigable stream" also owns the stream. Now, the definition of what is navigable is where the water begins to muddy. In 1997, a state court interpreted Georgia's 1863 navigability law to define a navigable waterway as one that can handle heavy barge traffic. "Nobody even heard of recreation, much less recreational canoeing, back in 1863," said Dan MacIntyre, an Atlanta business lawyer and paddler who began doing free legal work for paddler rights 10 years ago. For MacIntyre, the 1997 reading was "the ultimate horrific extension of where we are and the ultimate worst-case scenario. ... One person that owns an inch of land on either side of the river is all it takes. And they can close any river in the state that's not navigable by heavy barge traffic." The Georgia definition of

navigability is more restrictive than federal law. Thus, Georgia paddlers

and anglers typically fare better when their river passage cases are

heard in federal court, which is where the state's only ongoing river

passage case — the much-publicized dispute on the West Fork of

the Chattooga River in Rabun County — has been for the past two

years. "I think the Georgia courts are primed to hold that the federal definition preempts the state definition, certainly the federal courts have held that," said Atlanta attorney Michael Terry, a longtime advocate for the right of public passage. A settlement in the West Fork case — where owners of private land surrounded by the 750,000-acre Chattahoochee National Forest attempted to prohibit the public from floating the river — may be near. On April 6, the 230-acre tract was purchased by someone who may be friendly to the paddlers' cause. The new owner, Robert Reid, is president and co-owner of WaterMark, an Atlanta-based company that owns Perception Inc. and Dagger Canoe Co., two of the leading manufacturers in the paddle sports industry.

Reid has said he believes the public should have the right to float and fish the West Fork and that he has no plans to develop the land. Landowners stress cleanliness, stream careOnly a handful of Georgia landowners have closed rivers, either by posting signs, stringing cables across the water or guarding the banks themselves. The fact that more could do the same angers many paddlers."How could somebody feel like they own a river?" asked Gainesville kayaker Gary Gaines. "They shouldn't be able to stop people from recreational use of the Chattahoochee or any other river in North Georgia." As more riverfront land is developed, the chance for conflict increases. "If the damn paddlers want to canoe, they ought to get out and buy them a piece to canoe on," said Lovell, whose late brother Earl was a landowner in the West Fork of the Chattooga case. Lovell says his major gripe

against paddlers and floaters involves cleanliness. The garbage and

human waste he feels would accompany the river traffic — he points

to the Chattahoochee near Helen as an example — would ruin the

trout stream he has cared for over the past 40 years. That's why he

cabled off his section of the Soquee nearly 20 years ago. "We really challenge people to look at the way we care for the river through that mile-and-a-half and compare that to the mile-and-a-half that is publicly accessible above us," said Dockery. "There's really no comparison." MacIntyre pointed out that the Georgia Canoeing Association organizes dozens of river clean-ups each year. "It may be we're going to spend a lot of time in federal court the next 20 or 30 years deciding this river by river," he said. "That's not something I look forward to. I'd much rather be out there paddling." Recreation limits fuel debate in state parksAway from the water, where the line between public and private is less blurred, conflicts arise over what forms of outdoor recreation are allowed on public lands.For example, Tallulah Gorge State Park is the only state park that allows rock climbing, a sport whose enthusiasts are still reeling from the 1995 closure of the private road to Yonah Mountain, then one of the state's most popular climbing areas. Tallulah Gorge, in Tallulah Falls, also offers mountain biking, hiking and whitewater paddling. Park manager Bill Tanner says one reason Tallulah is on the cutting edge in outdoor offerings is because the park, established in 1993, is relatively new. "We had a certain amount of time that we could really thoughtfully, and in some cases scientifically, look at what we had and develop our management plan, rather than being forced to do it really quickly or to immediately adopt an existing management plan," Tanner said. Bureaucracy, he said, can make it difficult to change management plans designed for a different era. Many climbers say Cloudland Canyon State Park on the western edge of Lookout Mountain would offer some of the state's best climbing. But climbing isn't allowed. "We just follow what our department tells us," park manager Stanley Hammock said. Chris Watford, southeastern representative of the Access Fund, a national climber's advocacy group, hopes to parlay the success of climbing at Tallulah Gorge into access at Cloudland Canyon. He realizes it may not be easy. "I think sometimes (the parks') reaction is to curtail activities instead of managing it," Watford said. "If you don't have any budget, the easiest thing for you to do is to eliminate (the activity)." Liability aside, stewardship is crucialPublic and private landowners also raise concerns about liability. But is a landowner liable? According to Allen Padgett, manager of the state's Crockford-Pigeon Mountain Wildlife Management Area, the answer is no. Georgia's little-known recreational liability law provides immunity for landowners who allow recreational use of their land for free. The climbing walls at Crockford-Pigeon, near Lafayette, attract thousands annually. "Because we allow folks to go rock climbing and we don't charge them anything to do that, if they want to sue us, have at it," Padgett said. "God made the cliff and God made gravity." But does God stop frivolous lawsuits? The Southeastern Cave Conservancy has begun leasing or buying caves and assuming all liability involved in their use. "It gives the (landowner) a multi-million dollar liability backup policy that covers them in case somebody manages to try to sue," said conservancy member Chris Hall, a caver from Buford. "Just because they can't win doesn't mean it can't cost you a lot on lawyer fees, and that's what we negate." Often, it's not a question of liability, Hall added: "It's more a question of they don't want them long-haired hippie people out there." Padgett said groups trying to gain access can help their cause by educating land administrators about their activities, being sensitive to environmental concerns and showing a willingness to work with managers. Dedication to stewardship is working for mountain bikers, according Tom Sauret, executive director of the Southern Off-Road Bicycle Association. SORBA has built relationships with federal, state and local public land managers throughout the Southeast, said Sauret, an English professor at Gainesville College in Oakwood. "We don't just walk in and use it and leave it," he said. "The U.S. Forest Service has told us that we ... put more hours of working in the forest than any other user group." The give-and-take is necessary, Padgett said. "It's a privilege, not a right," he said. "The Constitution doesn't say nothing about rock climbing." See also: Dan Washburn is a sports writer for The Times in Gainesville,

Ga. |