July 4, 2002 — As a kookaburra cackled in the distance, a wallaby wallowed in the shade of a tall tree. Nearby, a red kangaroo hopped, then stopped. She stared at me quizzically. Her baby joey — face, feet and tail all peering out of her pouch — stared, too.

July 4, 2002 — As a kookaburra cackled in the distance, a wallaby wallowed in the shade of a tall tree. Nearby, a red kangaroo hopped, then stopped. She stared at me quizzically. Her baby joey — face, feet and tail all peering out of her pouch — stared, too.

Ah, the sights and sounds of … wait a minute … Dawsonville?

Where were the ear-splitting engines, the checkered flags, the Bill Elliott Coke machines? After all, this is the birthplace of motorsports, not marsupials. Right?

Well, just down the road from Thunder Road — where during prohibition, moonshine runners out-raced police cars and paved the way for the NASCAR drivers of today — sits the Kangaroo Conservation Center, an unassuming 87-acre plot that just happens to house the largest collection of kangaroos outside of Australia.

No signs lead to the property. An 8-foot bamboo gate opens slowly when visitors buzz themselves in. Entry is granted by reservation only.

The center does very little advertising, and yet its tours are consistently booked. Word-of-mouth and unsolicited media coverage — of which there has been plenty recently — have provided the center with all the publicity it needs.

The New York Times, in fact, ran a feature on the center in late May.

The New York Times, in fact, ran a feature on the center in late May.

“The phones have been ringing off the hook since then,” said soft-spoken Debbie Nelson, who, with husband Roger Nelson, opened the center in 1998. “I think people are just fascinated by kangaroos.”

And if it’s kangaroos people want, North Georgia, believe it or not, is the place to be.

Sherri Donovan, from Brooklyn, N.Y., read the New York Times piece and booked her family a flight that very night.

“Kangaroos are addicting,” Donovan said after an afternoon at the center. “The information you get, and the close-up contact with the kangaroos, I don’t think you can get it anywhere else.”

Roger Nelson would agree.

“In what we call our outback, you’ll see more kangaroos in the next hour than you would see if you took a trip to Australia,” he said proudly.

More than 200 kangaroos live at the center, and about 95 percent of them were born there. Other unusual creatures also call the center home. Like the tiny African dik-dik antelope, for example. Extend a finger, and the male will “mark” you with a brown tar-like substance secreted from a large gland underneath his eye.

The Nelsons opened their property to safari-like tours in 2000. Last year, more than 3,000 visitors passed through Dawsonville’s version of Down Under.

But the center is far more than just a marsupial amusement park. It is a working zoological breeding facility. Australia rarely allows its native animals to be shipped to foreign countries. The Nelsons have filled that niche.

The center has supplied kangaroos to zoos on four continents, including more than 100 zoos in the United States alone. Sometimes, zoos will send sick kangaroos to the Nelsons, who have shown a knack for nursing them back to health.

Throw in the tours, and it’s quite a bit to tackle. The Nelsons only have four full-time employees.

Throw in the tours, and it’s quite a bit to tackle. The Nelsons only have four full-time employees.

“It keeps us hopping,” Debbie said. She then looked down and smiled. The pun was unintended.

The center seems less a farm and more a family. All the animals there have names. Several kangaroos spent their first months of their lives in the Nelsons’ parlor, not a pouch.

“We get very attached to them,” Debbie admitted. “It’s sort of like raising a baby. They are very affectionate animals.”

We were sitting in the Nelsons’ office prior to the start of my tour when Roger stood up from his stool and said, “I’ll bring in Emily.”

Roger returned with what looked to be a plush doll nestled in his arms. Emily is an 8-month-old red kangaroo. Emily weighed less than a pound when her mother died. The Nelsons are her parents now.

Emily shook slightly when Roger brought her closer to me. It was the only way I could tell that she was real.

“They’re very shy animals,” Roger said. “Their first instinct is to hop away from danger. They’re not at all aggressive like some people perceive them to be.”

The Nelsons started raising exotic animals 20 years ago when they lived in Alpharetta. They began working with kangaroos four years later, and decided to focus on the animals of Australia when they moved their operation to Dawsonville in 1998.

That’s when the media started calling. Soon the Nelsons and their kangaroos were appearing on ABC’s “Good Morning America” and “Jack Hanna’s Animal Adventures.”

It’s been quite a ride for the Nelsons. Back in college, Debbie was an art history major. Roger has a degree in engineering.

“That’s what keeps life interesting,” Roger said. “You never know where you’re going to end up.”

You know, Roger, you’re right. I never thought I’d learn to throw a boomerang in the Bible Belt. Never thought I’d stare a 200-pound kangaroo in the eye there, either. But I did.

The tour begins with the boomerang and moves on to the blue-winged kookaburras. There are only five such birds in North America, we were told. All of them live at the Kangaroo Conservation Center.

The tour begins with the boomerang and moves on to the blue-winged kookaburras. There are only five such birds in North America, we were told. All of them live at the Kangaroo Conservation Center.

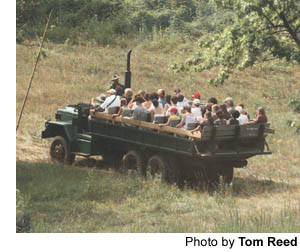

The highlight of the tour is the hour-long trip through the North Georgia “outback.” With Springer Mountain — the southern terminus of the 2,168-mile Appalachian Trail — looming in the distance, 35 of us squeezed into a converted 1968 Army truck that rumbled through 40 undulating acres.

Kangaroos, mobs of them, were everywhere. There were red kangaroos and gray kangaroos, both the eastern and western variety. Some hopped on by and paid us no mind. But most stopped and stared.

Kangaroos are curious creatures. Always looking, always listening. Their ears move independently. Their eyes are big and black and stare right through you. It’s like they’re trying to figure you out.

Kangaroos look rather lopsided, really. Their hind legs are huge, with long, floppy feet like clown shoes. Their tales are thick and sturdy. Their front limbs, however, are short and stunted. They dangle downward, as if carrying a small purse.

The largest kangaroo we saw was 7.5 feet from the tip of his tail to the top of his head. He weighed 220 pounds. His name was Red.

He stared at me. And I stared back.

I couldn’t figure him out.