January 31, 2002 — “GOT BEER??”

January 31, 2002 — “GOT BEER??”

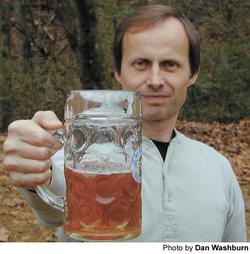

That was the question posed by Dennis Brown’s baseball cap. I’m assuming it was meant to be rhetorical. I was spending the day with the Chicken City Ale Raisers — Gainesville’s home brewing club — and they always “got beer.”

If they run out, they just make some more. But I think running out is against club rules.

We were in the Murrayville basement of Rick Foote, a longtime zymurgist (that’s baroque for brewer) and the club’s president. That’s a title he’ll hold for life, he often says, because nobody else wants it.

“Being here in the Bible Belt, it seems we must always fight the stereotype that we’re low-life drunks,” said Foote, 42, who moved to Gainesville from Pennsylvania, by way of Vermont, 10 years ago. “You mention beer or home brewing and people snicker. What’s the big deal? We’re all grown ups. I mean, beer is … beer.”

Well, perhaps not all beer is beer according to Chicken City Ale Raiser standards. There was quite a bit of Bud-bashing going on in the basement. Someone down there even referred to our nation’s self-proclaimed “King of Beers,” and its many imitations, as “American swill.”

And — at the risk of insulting 97 percent of Americans — I tend to agree. I prefer beer you can’t see through. The Ale Raisers were happy to hear this, and very eager to introduce me to their creations.

“Someone who drinks Budweiser — Joe Six Pack — isn’t going to appreciate this type of beer,” Lance Huthwaite, 32, a dentist from Clermont, said as he handed me a Classic American Pilsner that the club brewed “pre-Prohibition style.”

“Someone who drinks Budweiser — Joe Six Pack — isn’t going to appreciate this type of beer,” Lance Huthwaite, 32, a dentist from Clermont, said as he handed me a Classic American Pilsner that the club brewed “pre-Prohibition style.”

I looked at my watch. It was just after 10 a.m.

“I guess it’s never too early for a beer,” I said.

“Not if you’re brewing,” Richard Louise, a Gainesville stockbroker, said. “The rule is: if you brew beer, you can drink beer.”

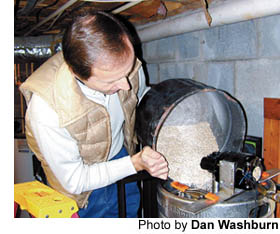

And we were brewing beer — from scratch. That’s what Foote’s basement was built for, it seems. It’s the laboratory of a mad zymurgist. Kegs and coolers, tubes and trinkets everywhere. Foote calls it the Whistle Pig Brewery.

It features two refrigerators. One for hops and yeast. The other for beer, lots of it. It flows freely from taps rigged to the fridge. (For those under 21, like Foote’s children, the tap to the far right serves homemade root beer).

Foote, recycling guru for Hall County, had the plumbing lines in his house re-routed for purposes of beer brewing. Turn a series of knobs on an intricate maze of pipes, and water flows pure from Foote’s well to an outdoor wood-burning heater. Then it travels into the basement through a spigot conveniently placed above Foote’s brewing contraption.

One catch: when filling the brewing kegs, the water to the rest of the Foote house runs dry.

“Are you turning off my water now?” Foote’s wife Carolyn called down from upstairs.

“Yes,” Foote replied. “Dishes and whatever else are going to have to wait for beer.”

“Yes,” Foote replied. “Dishes and whatever else are going to have to wait for beer.”

But this is nothing new for the Foote household. They were, after all, married on the first Saturday in May — National Homebrew Day — several years ago. (Foote claims that happened by accident.)

“Our second date was, ‘Come over to my apartment and see how we brew beer,'” Carolyn said. “But it’s fun. And it keeps him at home.”

Brewing kept Foote home Jan. 12. It kept five other Ale Raisers, and one newspaper reporter, at his home, as well. We brewed an ale — from barley to boil and points beyond — and the process lasted more than eight hours.

No one step is more important than the others, I was told. They all need to be done if anything’s going to be drinkable. But one thing is paramount for potability: cleanliness.

Thankfully, and with all due respect to the late Phil Hartman, Foote is fine fill-in for The Anal-Retentive Brewer.

“If you’re brewing at your house and Rick’s there,” said Brown, 52, of Cumming, whose “GOT BEER??” hat lights up, by the way, “you set a piece of equipment down and it’s cleaned and sterilized before you can pick it back up.”

That’s a good thing. It’s as much about the science as it is about the suds. We followed a strict recipe — with line graphs and everything — down to the degree, down to the second.

That’s a good thing. It’s as much about the science as it is about the suds. We followed a strict recipe — with line graphs and everything — down to the degree, down to the second.

“You can get as deep into it as you want. It involves a lot of different disciplines: engineering, physics, chemistry, biology,” said Foote, who in 1996 attended a weeklong course on microbrewery and pub brewery operations at the Siebel Institute of Technology in Chicago.

Now, science has never been my forte. Never will be. So, I could throw out a lot of mumbo-jumbo here about mashing, sparging, enzymes, wort and the like. But you’d know I was faking it. You’d know I was just in it for the beer.

And it’s good beer, too. On Monday, I tried some of the batch I helped brew — OK, I mostly just watched — and I was rather impressed. Last year, the Ale Raisers won eight ribbons at the Peach State Brew Off.

“The best part is drinking it,” said Brown, a carpenter at Gainesville College. “Even if it doesn’t come out perfectly, it’s still a decent beer.”

Added Foote, “The kick I get is that people go out and buy beer like this. And I can make it in my home.”

You don’t need a set-up like Foote’s to brew, either. Beginners can get started for less than $100. Club member Phil Farrell, an airline pilot from Cumming, brews on top of his wife’s stove. The most he can make at once is five gallons, which is about one-third of what we brewed at Foote’s place.

“I really can’t do much bigger than that,” Farrell said. “The burners wouldn’t be able to handle it. Plus, my wife would kick me out of the house.”

Man has brewed beer, in some form or another, for around 5,000 years now, but not until 1993 could you legally do it in your home in Georgia. Interestingly, it was Georgian Jimmy Carter who passed the federal legislation that legalized home brewing in 1978.

The beer we made was a clone of Sierra Nevada’s Celebration Ale, which the San Francisco Chronicle once dubbed the “best beer ever made in America.” Sierra Nevada actually lists all of the specs and ingredients for its beers on the Internet.

The beer we made was a clone of Sierra Nevada’s Celebration Ale, which the San Francisco Chronicle once dubbed the “best beer ever made in America.” Sierra Nevada actually lists all of the specs and ingredients for its beers on the Internet.

“I’m sure they’re flattered that home brewers would want to emulate one of their favorite beers,” Foote said. “I mean, who’d want to clone a Budweiser?”

By that time, most of our day of brewing was finished. All we had left to do was add the yeast and let our concoction ferment for two weeks.

It was after 5 p.m. I knew because I looked at Foote’s … hey, wait a minute. Is that a Budweiser clock?

Foote looked a little ashamed. Then he said, “It was free.”

For more information on the Chicken City Ale Raisers, email them.