December 12, 2001 — Ranger Mitch Oliver looked tired. His eyes already showed the wear of a full day’s work. And we still had a long night ahead of us.

“There are days when you might work four or five hours,” said Oliver, 26, of Buford. “And there are days you’ll work 16 hours. Today is going to be one of those.”

Oliver’s job title is a mouthful. He is the Gwinnett County conservation ranger for the law enforcement section of the Georgia Department of Natural Resources Wildlife Resources Division.

Most people just call him the game warden.

Like the 250 or so other rangers in Georgia, one of Oliver’s primary responsibilities during the fall is known as the night hunting detail.

It’s a stakeout of sorts. Following leads, rangers hide in the forest for hours, and wait — wait for someone to shine a spotlight or shoot a gun.

“It is kind of long and boring,” admitted Sgt. Rick Godfrey, of the DNR’s Gainesville office, who has worked night hunting details for more than 15 years. “It can be cold. It can be wet. It’s tough. And you spend a lot of time away from your family.”

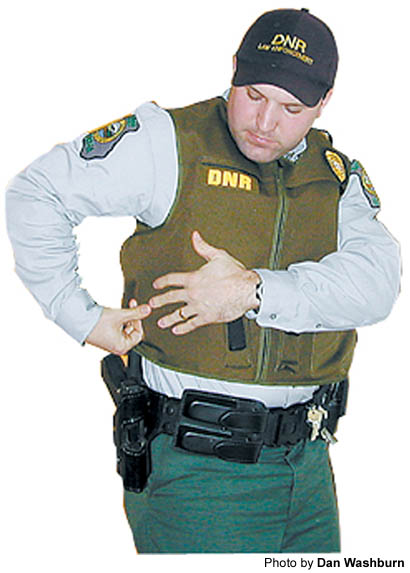

It can be dangerous, too. This is one time when the police can be pretty certain the people they are after are armed. Oliver and I both wore bullet-proof vests for our venture on Saturday night.

Hunting deer at night has been a problem ever since man has had shotguns and spotlights. Basically, it’s considered cheating. You’re taking the hunt out of hunting.

“Hunting is a sport where the animal has somewhat of an advantage,” Godfrey explained. “By going and spotlighting them at night, you have taken away their natural advantage in the daytime hunt. That’s just not an ethical way to hunt. It’s like shooting a dove off of a power line.”

Deer use the supposedly safe cover of darkness to feed and roam. Bright lights blind deer, and they become easy targets.

Some night hunters are looking for a trophy. They will shoot a buck, cut off its head and leave the body to rot.

Others moonlight in the murder business. Armed with high-tech night-vision equipment, they can take out several deer each evening and sell the carcasses for cash.

“These guys are not hunters, they are poachers,” Oliver said. “And it could deplete the resource real quick. You’re taking away from the sportsman that does it the legal way. It’s very unethical.”

It’s also very illegal. In Georgia, a first-time night-hunting offense carries a minimum fine of $500, up to 12 months in prison and a two-year suspension of hunting privileges.

Even spotlighting deer, considered “blinding wildlife,” is against the law.

And it is the job of the DNR rangers to see that these laws are enforced, even if it means sitting in a truck alone in the woods for hours at a time.

Occasionally, it’s the job a of a journalist to join them. I think Ranger Oliver was just happy to have someone to talk to.

“We get a lot of time to think about things, that’s for sure,” said Oliver, his can of Copenhagen and bottle of Mountain Dew nearby for the long night. He had been out on a night hunting detail until 2 a.m. the previous day and was back on his regular rounds by 6 a.m.

Later that night, we were following a lead in Jackson County. Oliver and other rangers had been staking out this particular plot off and on for two months. Catching poachers can be a slow process.

“It’s all guess work,” said Godfrey, who has made several night hunting arrests over the years. “You hope you’re thinking like the poachers, but you never know.”

Oliver is approaching his one-year anniversary with the force. He has yet to catch a poacher.

“I don’t know if I’m just unlucky or what,” said Oliver. “If we’re out here, we’re wanting to see business. But you’re not going to catch them every night. Catching one or two per deer season is pretty good.”

And those one or two arrests, Oliver has been told, make all the lonely weekend nights in the woods worthwhile.

“It can be the most exciting part of the job,” Oliver said. “Especially if you’ve got shots, the adrenaline gets to going. And then other times, the majority of the time, you might never see a vehicle.”

Most of the shining and the shooting comes from inside automobiles. Poachers tend to be lazy in addition to unlawful.

At roughly 9 p.m., we positioned Oliver’s truck in the trees near a field adjacent to a backwoods road. Two other ranger trucks were hidden in other areas of the acreage.

“Hang on,” Oliver said as we backed into the brush. “This may get a little bumpy.”

It was a mild night for December. Where we were, hay bales outnumbered homes. And the stars in the cloudless sky outnumbered all.

We cut the engine off and sat there. No radio. No reading. Just watching and waiting for the random car to pass by.

Each time one did, my heart raced. Imagination can run wild in the woods. For each automobile, I painted a scenario of skullduggery and subterfuge.

They were likely just folks heading home, but the manufactured excitement made the hours pass faster.

The poachers appeared to be elsewhere on this day. And after four hours, and very little action, the rangers decided to call it a night.

Shortly after 1 a.m., Oliver rubbed his eyes and started up his truck. He had to be back at work in six hours.

“Well, if nothing else, you can write that we’re dedicated,” Oliver said. “Dedicated or stupid, one.”