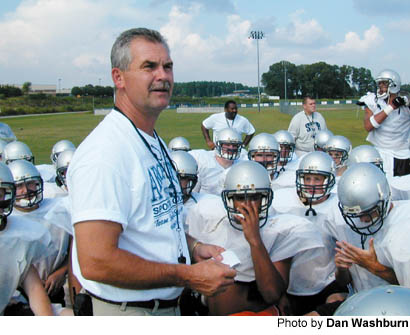

“You gotta love it,” West Hall High head football coach Tim Marchman says of his job. “It’s just a way of life around here.” Coaching high school football is a year-round job, filled with long hours and sacrifice. Sporting Life columnist Dan Washburn caught a glimpse of the life of a coach when he followed Marchman and his staff around for one day in early August.

August 26, 2001 — Tim Marchman looks like a football coach.

He is dressed in a T-shirt, shorts and running shoes. A whistle hangs around his neck. So do a pair of eyeglasses.

And it’s those spectacles — and the rather large specs of gray taking over his full head of hair — that reveal the fact that Marchman has been at this football coaching thing for the past 26 years of his life.

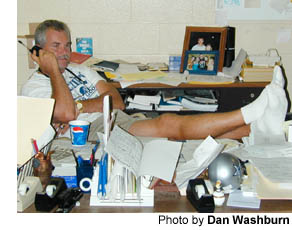

But Marchman, head coach at West Hall High, remains spry and sprightly. In his cluttered coach’s office — which he prefers to call “a dang workroom” — he rushes around like a rookie in need of some Ritalin in the hours leading up to the Spartans’ practice.

Marchman is bouncy and alert, and obsessed with football. He has been thinking about football since the moment he woke up. Football, and the oppressive summer heatwave that has Georgia, and the rest of the nation, in a suffocating headlock.

It’s Aug. 8, and by now heat stroke has already claimed the lives of several football players across the country. Marchman is worried, and he can’t stop talking about it.

It’s Aug. 8, and by now heat stroke has already claimed the lives of several football players across the country. Marchman is worried, and he can’t stop talking about it.

“Yesterday, we practiced in the heat and it was very, very ugly,” says Marchman, whose voice has been hoarse and gravelly — like he’s just gotten done reaming out a receiver who ran the wrong route — since I met him three preseasons ago.

“It’s going to be ugly again today. I’m very aware and very stressed out about this situation.”

Marchman springs up from his chair and hustles over to his desk. I stand up to follow, but Marchman holds up his hand — similar to a running back stiff-arming a defender — and says, “I’m coming back.”

He shuffles through the papers on his desk, grabs the ones he wants, and returns to his seat.

“This morning, the first thing on my mind was this,” Marchman says, presenting me with a photocopy of his morning notes, which are directed at his coaches, and pertain specifically to handling the heat:

“1. We are the leaders! Be prepared — keep the players 1st. Consider their well-being first & foremost. If there is any question of players, water them down, get them out of drill, cool them off, and watch them carefully.”

There are seven points in all, handwritten on a piece of legal paper.

“I am very, very, very stressed out about how we’re going to handle this heat,” Marchman says again.

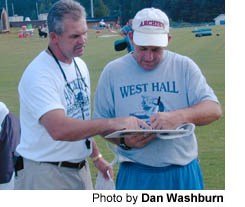

He has other papers in his hand, as well. He hands one of them off to me. It’s his practice schedule, which he also scripted before breakfast.

“And then I did this one,” Marchman says, laying another piece of paper, the practice schedule for the following day, on my lap, “to stay a day ahead of myself.”

“And then I did this one,” Marchman says, laying another piece of paper, the practice schedule for the following day, on my lap, “to stay a day ahead of myself.”

Marchman is meticulous, to be sure. On the weekends, he plans his week. During the summer, he plans his entire preseason. I don’t think to ask when he finds time to plan his planning.

“We do planning constantly,” Marchman says. “It takes hours of planning.”

Even during the supposed non-football hours of Marchman’s day, he’s thinking about football. Even during the academic meetings that sometimes fill his school day.

He leans forward and whispers to me: “Yesterday, I made out a practice schedule during one of those meetings. Now I listened, but my time is valuable. You’re fixin’ to find out. This place is a bees’ nest for the next hour.”

Sure enough, as players and coaches arrive, the Spartans’ fieldhouse is abuzz.

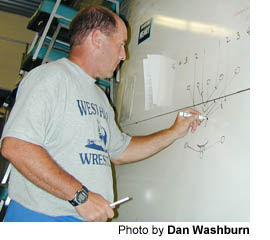

For West Hall’s 10-man coaching staff, it’s nonstop work — starting more than an hour before practice and sometimes not ending until after midnight. And a rather small percentage of it, surprisingly, has to do with Xs and Os or punts and passes.

For West Hall’s 10-man coaching staff, it’s nonstop work — starting more than an hour before practice and sometimes not ending until after midnight. And a rather small percentage of it, surprisingly, has to do with Xs and Os or punts and passes.

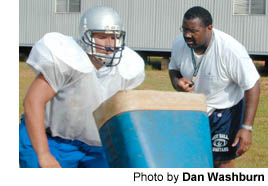

It is less than an hour before the 4:30 p.m. practice time. Defensive line coach Tyrone Lucas is in the locker room taping ankles. Offensive coordinator Paul Alexander and offensive line coach Brad Whitfield are in the equipment room handing out shorts and T-shirts. Running backs coach Robbie Bailey is in the shower, filling up cooler after cooler of ice water.

Meanwhile, Marchman does his best Don Corleone. Anyone with a problem approaches him.

One player has blood in his urine, and Marchman sends him to see the trainer. Other players come armed with their mothers and notes from their doctors.

One put his arm in a sling with a dirt bike accident. One can’t practice because he has to see his chiropractor.

Marchman wishes them well and sends them on their way.

By 4:21 p.m., most players are suited up, already on the field. Marchman is a stickler for punctuality.

By 4:21 p.m., most players are suited up, already on the field. Marchman is a stickler for punctuality.

“Those that come in late will be,” Marchman says, pausing to take a bite out of an apple, the only thing I see him eat all day. “Well, they’ll wish they didn’t.”

Minutes before practice is set to begin, coach Alexander is on the phone, trying to make sure the team’s cleats arrive before its season opener against Gainesville. Evidently, there was some sort of mix-up.

I’ve heard of kickers going barefoot, but not entire teams. Perhaps the Spartans will be the Zola Budds of Region 8-AAAA this season, I wonder to myself.

“We’re fixin’ to hit the field,” Marchman says.

The headcount starts immediately. It’s still summer. School’s not in yet. And some players are unaccounted for.

This happens throughout the summer. Some players go on mission trips for their churches. Some must attend summer school to be eligible to play. Some come from split homes and live part-time out of the area. Some go on family vacations scheduled, much to Marchman’s dismay, during his practice weeks.

And other players would just rather not run around in the summer heat.

“How do you make it fair to everybody?” Marchman asks, unable to find an answer. “That’s something that’s going on all the time.”

Later on in this day, one player waits until practice is more than halfway finished to tell Marchman he must leave early. The reason? He’s going to be late for his baptism. How do you say no to that?

Later on in this day, one player waits until practice is more than halfway finished to tell Marchman he must leave early. The reason? He’s going to be late for his baptism. How do you say no to that?

There are folks, however, whose attendance at practice is rarely in doubt. They are the spectators, many of them parents of players, who surround the field with their cars and set up lawn chairs on the sidelines. Sometimes they do more than just watch.

“I’ve had parents in my drills before,” Marchman says. “It’s the strangest thing I’ve ever seen. Some of them come all the way out here. Some are very critical. Some are very supportive. Who knows?

“But my practices are open. I don’t have anything to hide. I just hope they don’t get hit.”

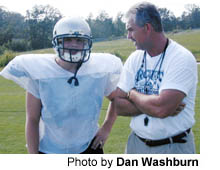

Marchman never stops being a coach. As we walk onto the practice field, players proceed with their specialty drills. And no one escapes Marchman’s gaze as he makes his way from one end of the field to the other. He sees all, and never passes on an opportunity to teach.

“I want you catching facing forward with a basket catch,” Marchman says to a player, not stopping his stride. “I want it caught facing the punter, you hear me?”

“Yes, sir” is always the answer.

Marchman grew up in Rabun County and played defensive back for Carson-Newman College, in Jefferson City, Tenn., in the early 1970s. He was on the Eagles team that played for the NAIA national championship in 1972.

Marchman grew up in Rabun County and played defensive back for Carson-Newman College, in Jefferson City, Tenn., in the early 1970s. He was on the Eagles team that played for the NAIA national championship in 1972.

Like many high school coaches, Marchman has bumped around from place to place. Gilmer County. Lafayette. Bremen. He was defensive coordinator on the West Rome team that won the Class AA state title in 1984.

But Marchman, entering his ninth year as the Spartans’ head coach, has made West Hall the longest stop on his coaching carousel.

“I’m real proud of that,” Marchman says. “I’m real happy to be in this area.”

Practice, actually, ends up being a rather small portion of a coach’s day, when all the hours are tallied up. Still, most of the day’s work, in one way or another, leads up to practice. And the work after practice leads up to the next one.

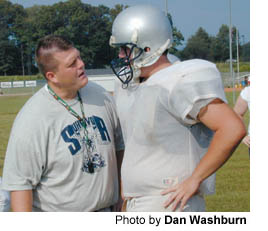

Now, don’t get me wrong. Practice is still work. Some of the coaches appear to sweat as much as the players. These preseason practices are labor intensive, full of teaching and technique.

Marchman says repeatedly, “I’m not worried about Gainesville at this point. I’m worried about the West Hall Spartans.”

And Marchman admits the Spartans have a bit to work on. They did, after all, lose 21 seniors from last year’s team that advanced to the second round of the Class AAAA state playoffs, West Hall’s first trip to the postseason since 1995.

I assume, midway through practice, that the Spartans are getting more out of the coaches’ instruction than I am. I, to be honest, am a little bit lost. Back in high school, I was a basketball and baseball man. This football stuff is complicated.

I assume, midway through practice, that the Spartans are getting more out of the coaches’ instruction than I am. I, to be honest, am a little bit lost. Back in high school, I was a basketball and baseball man. This football stuff is complicated.

For me, practice is a haze of traps and timing, schemes and stunts. Perhaps I can blame some of my confusion on the heat. But I doubt it.

“I might be overbearing you,” says Marchman, who would often turn to me and try to explain what was going on. “But I’m trying to give you all the info I can. When you’re through here, I think it will almost be like going to a college.”

One part of practice I understand, and readily participate in: the drink breaks. There were many of them. Often, Marchman and his coaches force the players to drink, telling them they can’t stop drinking until a coach says so. There is so much drinking of water going on, that members of the old guard — Bear Bryant and the “water is for wussies” brethren — are likely tossing in their graves.

But, on this day, the heat is hot, as they say, even for someone like me who is simply observing.

Speaking of observing, as the practice grinds on, there are plenty of people doing just that.

“I told you they’d show up,” Marchman says with a grin. Spectators line the field like they’re preparing for a parade.

After nearly three hours under a searing sun, the last drink is drunk, the last drill is run. The Spartans gather at midfield and bow their heads in prayer. They survived the heat to practice another day.

After nearly three hours under a searing sun, the last drink is drunk, the last drill is run. The Spartans gather at midfield and bow their heads in prayer. They survived the heat to practice another day.

As the players shower and head home for supper, the coaches prepare for the next phase of their day.

Coach Whitfield starts loading the team’s practice clothing — that’s 75 players’ worth — into washing machines. Yes, coaches get laundry duty, too.

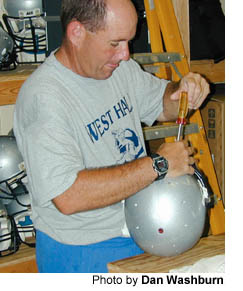

Coach Alexander fixes broken helmets in the equipment room. Coach Lucas prepares a list of players absent from practice — Marchman will telephone each one that night.

The rest of the staff sweeps up the fieldhouse, gathers equipment and prepares for the next practice, which begins at 8 a.m. the following day.

After the chores are done, or at least begun, the coaches gather in the “dang workroom” to discuss personnel matters: what players looked good, what players didn’t, what players didn’t show up, and why. This can take hours.

Then, it’s time to go over the schedule for the next day’s practice.

These are long days, indeed. One night at the fieldhouse — one that eventually turned to morning — Whitfield figured it out: He was being paid about a nickel an hour to coach high school football.

These are long days, indeed. One night at the fieldhouse — one that eventually turned to morning — Whitfield figured it out: He was being paid about a nickel an hour to coach high school football.

But the coaches love the game. They love the kids. They’re obviously not in it for the money.

“I’m trying to make a difference in kids’ lives, that’s the biggest reason I do it,” Lucas says. “I had high school coaches that made a big impact on my life. I always wanted to try to do the same.”

It’s now after 9 p.m., and Lucas is helping Whitfield move some of the practice uniforms into the dryer.

He continues, “We’re also here to be a father figure. I’d bet over half of the boys that we coach, they don’t have daddies at home.”

But many of the coaches are daddies themselves. They have children waiting at home. They have wives. And they admit that the job can sometimes put a strain on the family.

But many of the coaches are daddies themselves. They have children waiting at home. They have wives. And they admit that the job can sometimes put a strain on the family.

“Well,” Marchman pauses before answering my question: What does his wife think about his 100-plus-hour-a-week profession? “She’s a coach’s wife. And she’s not real happy about it at all. But she’s learned to live with it, because this is my passion. This is my love. And I love kids. And she loves kids. She teaches kindergarten.”

At 9:42 p.m., Marchman calls his wife to let her know that he’s heading home.

It’s an early night for him. But he’ll be back at the field house in just over nine hours to do it all again.

And he’ll love every minute of it.