“We said there warn’t no home like a raft, after all. Other places do seem so cramped up and smothery, but a raft don’t. You feel mighty free and easy on a raft.”

— Huckleberry Finn

August 14, 2001 — Marshmallow Island. That’s what we called it, at least.

It’s an overgrown oasis, a small sanctuary stuck in the center of the Susquehanna River, the waterway that flows through my hometown of Bloomsburg, Pa.

On many a prosaic summer night, my high school friends and I would find ourselves sitting around the poker table, dealing out dozens of ideas: How would we get to the island? What would we find when we got there? And does a full house beat a flush?

Marshmallow Island symbolized, to us, the opposite of everything ordinary, humdrum and repetitive about teenage life in Smalltown, U.S.A. But, for whatever reason, we never made it out there. Well, one of us did — but about that story, I am forever sworn to secrecy.

The Bloomsburg Police Department might be able to answer your questions, however.

No, the rest of us never made it out to that island. Never gave it a serious try, really. Most grown men, I’ve found, have similar unrealized pipe dreams, leftovers from our youthful halcyon days — when anything seemed possible.

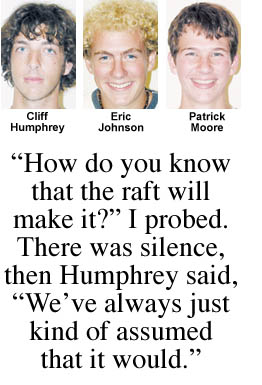

Naturally then, I was intrigued by the story of Cliff Humphrey, Eric Johnson and Patrick Moore, three local teenagers who planned on sailing a homemade raft the length of the largest lake in Georgia.

Naturally then, I was intrigued by the story of Cliff Humphrey, Eric Johnson and Patrick Moore, three local teenagers who planned on sailing a homemade raft the length of the largest lake in Georgia.

“I think the word is passion,” Humphrey said to me over the phone on the eve of their July 29 departure. “We’ve never seen the other part of the lake. We’ve only seen our own little cove. It’s just kind of a dream of ours.”

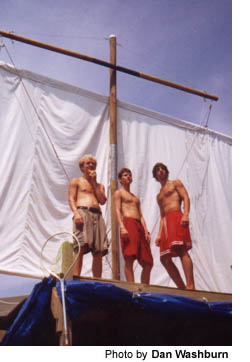

Their intended Lake Lanier course was more than 20 miles, south from Thompson Bridge Park to Buford Dam. And their intended vessel — 20 feet long, 10 feet wide, and 22.5 feet tall — was still under construction, still blocking Humphrey’s parents’ garage, as it had been for most of the summer.

“You’ve tested the raft out, right?” I asked.

“Not exactly,” replied Johnson, also on the phone at the time. “We’re taking it down to the lake tomorrow.”

“How do you know that the raft will make it?” I probed.

There was silence, then Humphrey said, “We’ve always just kind of assumed that it would.”

Now, that assumption was based on some experience. These boys, after all, had been building rafts together since middle school.

Their early rafts were rudimentary, with small log-and-styrofoam decks and sails made out of old shower curtains. They tried short day trips on the north end of Lanier, and were surprised by their success.

“When we first made a little raft with a sail and it was moving by itself,” Humphrey explained, “we were like, ‘Wow. We made this. And we’re going places.'”

This fall, the rafters will all be seniors in high school — Humphrey at Heritage Academy, Johnson at Lakeview Academy and Moore at North Hall. They saw this summer as a last hurrah, of sorts — and a final chance to make their dream come true.

Just one day before these three boys and their boat named “Evening Dawn” were scheduled to set sail, the weather report on the lake was calling for scattered thunderstorms over the next several days. Thunderstorms mean wind. And wind fills sails.

“We originally thought it would take a week,” Humphrey said at the time. “But, who knows? We might get there a lot faster than we thought.”

It wouldn’t be long before the boys would begin to doubt whether they would make it to Buford Dam at all.

Sailing a homemade raft is far from an exact science. So meeting up with the rafters on Day 2 of their journey was not easy. We couldn’t set a specific place to meet. Rather, I needed to be where the raft was when it happened to be there.

Thankfully, modern-day Huck Finns carry cell phones.

After some trial and error, we pinpointed their location — and I realized it wasn’t very far from their starting point at Thompson Bridge Park.

So I sneaked out onto a private pier and scaled a rocky shoreline to where the raft was grounded, motionless … huge! I suppose when they quoted the raft’s dimensions to me over the phone, it didn’t quite register. This wasn’t a raft. It was a floating dock.

“This is impressive,” I said.

“Yeah, I know,” Humphrey said. “It’s like a house boat. Let me take you upstairs.”

Yes, he said “upstairs.” The raft also has a long rudder, two adjustable keels, and an 18-foot-by-12-foot sail attached to its 16-foot-tall mast.

Yes, he said “upstairs.” The raft also has a long rudder, two adjustable keels, and an 18-foot-by-12-foot sail attached to its 16-foot-tall mast.

The raft’s pontoons are made of 10 55-gallon plastic oil drums the boys secured last fall, when planning for the voyage began. A frame made of iron supports the lower deck which, like the rest of the raft, was built with treated lumber and hundreds and hundreds of screws.

Such a project requires a little help. The rafters, all Eagle Scouts, received advice, funding and donations from West Marine, Regions Bank and Home Depot. They called on Steve Humphrey — Cliff’s father, the rafters’ Scoutmaster, and a longtime do-it-yourselfer — to do the bulk of the handiwork.

The boys refer to Mr. Humphrey as “Skipper.” They took to calling me “Lieutenant Dan.”

Yes, the raft was a site to behold. But it wasn’t moving. It was stuck in a cove, still hundreds of yards north of Thompson Bridge.

“Oh, there’s plenty of wind,” Johnson said. “It’s just blowing the wrong way.”

He then tossed into the lake a life preserver roped to the raft’s bow. He jumped into the water, and like a human tug boat, swam the raft away from the shore. It was a tactic that worked surprisingly well.

But once Johnson stopped paddling, we stood still. The rafters were prepared for such downtime, however. They would take turns reading from such heady tomes as “La Morte D’Arthur,” “King Lear” and “Heart of Darkenss” — some of which was required summer reading for school. More obvious choices — “The Raft” and “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” — made the trip, as well.

They even have their own raft music, albums full of old Irish sea chanteys, that they listen to only when out on the water. But they forgot the batteries to their CD player, and instead broke into song:

“As I walked down on Broadway one evening in July,

I met a maid who asked me my trade, and ‘Sailor John,’ said I.

And away, you santee, my dear Annie.

Oh, you New York girls, can’t you dance the Polka?”

Thompson Bridge came into view, and remained there for the remainder of my stay on the raft. We crept toward it gradually — sometimes aided by the sail, often aided by our arms and the paddles they held — and I decided I wasn’t going to leave until we floated underneath that bridge.

That finish line was realistic, I thought. But Buford Dam was a different story. To get there, it seemed, the rafters would need another month. And that wasn’t good. Moore’s first day of school was 12 days away.

“Maybe they’ll postpone school if we’re not done yet,” Moore chuckled.

The boys thought about changing their plans. Perhaps they’d just see how far they could go in a week. The following day, they actually considered getting towed to the dam and starting their trip from down there — all the wind appeared to be blowing north.

A car horn honked from atop Thompson Bridge. Then another. The rafters made the front page of that day’s issue of The Times, and they were getting noticed. Their plans were public — there was no turning back now.

We eventually did drift under Thompson Bridge … slowly. There was minor celebration when the raft cleared the bridge, and major consternation when we started heading back toward it.