May 1, 2001 — I have studied the videotape, stared at the photos.

I have done so repeatedly. And each time, I cock my head to the side and squint skeptically.

Is that really me? Did I really do that?

Then I snicker and release a wide satisfied smile. Because each time, the answer is yes.

I jumped out of an airplane 14,000 feet in the sky. I really did. And I think I might do it again.

It’s been only 11 days since I fell 10,000 feet at 120 mph with a guy named Wild Willie strapped to my back. Just 11 days since we floated the final 4,000 feet under a nylon canopy of yellow, red and green.

But from the moment my feet returned to Earth and touched down on a runway of grass, I have felt a dubious sense of detachment from the whole endeavor.

A 50-second freefall through clouds and cold thin air satiates the senses. It’s incomparable. It’s incomprehensible.

A 50-second freefall through clouds and cold thin air satiates the senses. It’s incomparable. It’s incomprehensible.

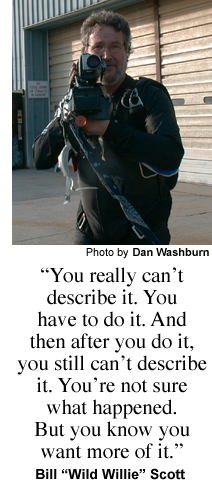

“You really can’t describe it,” said Bill Scott, the 51-year-old owner of Skydive Monroe, who with more than 6,400 jumps to his credit has well earned the Wild Willie moniker. “You have to do it. And then after you do it, you still can’t describe it. You’re not sure what happened, but you know you want more of it.”

Some skydivers told me about “blackouts” — large portions of their first jumps missing from their memory banks. Their minds short-ircuited. The sensation was too abstract.

Humans aren’t supposed to jump out of perfectly good airplanes, thus the body rejects the notion.

I believe I remember most of my first jump. I close my eyes and mental snapshots fill my mind.

But that’s all they are — snapshots. I can’t play them back continuously. I can’t even put them in the proper sequence.

It’s kind of like waking up and trying to piece together a dream. You’ve got many of the parts. But somehow they never add up to anything manageable.

Now when I look back on those 10 most exhilarating minutes of my life, I’m not sure if I am doing so based upon the experience viewed through my own eyes or through the lens of a video camera attached to another jumper’s head.

They say it takes a few jumps before the feeling of falling flees — then you start to fly. And the search for that sensation is what will likely send me back to the sky.

There were several times back on April 20 that I thought my first skydive would never even get off the ground. Wind made the Skydive Monroe hangar rattle most of the afternoon. My 1 p.m. jump time came and went. The empty hours of anticipation that followed didn’t do much to calm my nerves.

My ever-anxious mother called me at 2:14 p.m. from Pennsylvania to make sure everything went OK. She seemed happy to hear my voice — and then I told her I hadn’t jumped yet.

My anxiety first arrived during the drive to Monroe, located about an hour due south of Gainesville. I was almost at the airport. I saw the “SKYDIVING” sign along the side of the road. I made the turn, and my stomach turned.

From the moment you set foot in the hangar, it is made abundantly clear that the act of skydiving can be hazardous to your health. The “assumption of risk agreement” warns those semi-sane souls who choose to jump out of airplanes that they can be “SERIOUSLY AND PERMANENTLY INJURED OR EVEN KILLED.”

I took a deep breath and signed my name below.

It didn’t end there. I signed my name a total of 49 times. After a while, I stopped reading the statements I was agreeing to. They were too depressing.

It didn’t end there. I signed my name a total of 49 times. After a while, I stopped reading the statements I was agreeing to. They were too depressing.

“I HAVE FOREVER GIVEN UP IMPORTANT LEGAL RIGHTS.” So read one of my favorite passages. I also enjoyed the one that told me even though I might not have initialed every paragraph on the document, it would be assumed that I did.

In all, there were six pages of waivers to be signed. The words “injury” and “death” often appeared in bold type, capital letters — or both.

I visited the hangar restroom several times.

While we waited for the winds to settle, I sat down with ol’ Wild Willie as he worked on an airplane engine (not the one we’d be relying on, I was assured). Talking to him put me at ease.

He told me about reserve chutes, automatic activation devices, emergency procedures. He took me through the whole process, step-by-step. And he said it all with a smile.

“I’m a little conservative, I guess,” Scott said. “But I’ve got sixty-four hundred jumps for a reason. And I hope to make another sixty-four hundred.

“It’s absolutely the most phenomenal thing you can do for yourself. It’s the best thing in the world.”

Scott’s been skydiving for 25 years, teaching for 23. He opened his drop zone in Monroe eight years ago. Each year, Skydive Monroe takes clients on more than 2,000 tandem jumps — the simplest way to experience skydiving.

That is if the wind cooperates. I was beginning to doubt that it would. But at 4:49 p.m., Scott’s voice sounded over the intercom: “Let’s bring it in, and get ready to go skydiving.”

I visited the restroom, again.

The group suited up and sauntered over to our small dual propeller plane.

Skydivers walk with a strut. They have to. Those harnesses can be quite constricting.

Twelve of us squeezed inside that plane. In a matter of minutes, only two would remain: the pilot and Times sports editor Rob Joesbury. I’ll get to them soon.

The plane took off, and that was that. There was no turning back now.

I watched the altimeter on Scott’s wrist read higher and higher. I looked at the clouds outside the airplane window and realized I would soon be among them.

Someone remarked how cold it was in the plane. I couldn’t stop sweating, remembering fondly the feeling of solid ground.

“Take a deep breath,” Scott said. “You’re nervous. I can tell. I can feel your heart beating through the back of your chest.”

Everything was happening so quickly. From hangar to plane to midair, it was all a blur.

“Are we hooked together yet?” I asked Scott, whose chest was my backrest on the plane.

“Yes, Dan,” he chuckled. “Don’t worry.”

We had reached our desired altitude, nearly 14,000 feet. The other, more experienced jumpers smiled and waved as they filed out of the airplane. The scene was surreal. Kind of like the old clowns-in-the-Volkswagen-Bug routine, but reversed.

We had reached our desired altitude, nearly 14,000 feet. The other, more experienced jumpers smiled and waved as they filed out of the airplane. The scene was surreal. Kind of like the old clowns-in-the-Volkswagen-Bug routine, but reversed.

The others had already disappeared, literally into thin air, by the time Scott and I knelt inside the open airplane door. I leaned out, and my head hit the sky. The wind was hard and cold and uninviting. Clouds blocked my view of the Earth below.

It was time. Scott and I rocked back and forth as he yelled in my ear: “Ready, set, JUMP!”

This is my favorite part of the video — the moment right before we exit the plane — because unexpectedly, unexplainably, I am smiling.

Fear evolved into fun. Wild Willie and I floated somewhere between reality and Georgia.

I screamed instinctively and never stopped. Air occupied my mouth and made it dry. Then the plane nose-dived right before my eyes.

The pilot had asked Joesbury whether he wanted the “regular” or the “special.” Joesbury didn’t know what he was talking about, but said he wanted the special anyway.

The pilot had asked Joesbury whether he wanted the “regular” or the “special.” Joesbury didn’t know what he was talking about, but said he wanted the special anyway.

(“Your buddy got kind of surprised,” the pilot told me later. “When you ask for the special, you get it.”)

At that moment, I was happy to be outside the plane, plummeting toward our planet at 120 mph. But that’s not what it felt like.

In my mind, I was hovering on the hard air beneath me. And the horizon, the clouds, the green fields below bolted upward. My own world stood still.

Then Joe Bennett, the in-air photographer, drifted toward me, tapped me on the shoulder and woke me from my dream.

I lost track of time. Fifty seconds seems longer when you’re carrying on in the clouds. Scott pulled the rip cord and our canopy filled with air.

“Oh man! Oh man! Woooo!” I couldn’t think of anything else to say.

“Well, what do you think?” Scott asked as he guided our chute over the countryside.

“Amazing!” I shouted.

Then I paused, and stared back up at the sky.

“This is going to be hard to write about.”