September 26, 2000 — The fishermen stared at us. That’s about all they could do.

Their once tranquil fishing hole on Lake Lanier suddenly became Atlanta Motor Speedway.

A large flash of purple and orange is likely all they saw. But they could feel the wakes. And they could hear the engine. Oh yes, they could most definitely hear the engine.

I thought about offering the anglers a friendly wave. A blurry olive branch of sorts.

But I couldn’t. I was too busy working the throttle of Brian Hollis‘ pleasure boat. And it’s a behemoth: 28 feet, two tons, 500 horsepower. That’s a lot of pleasure.

The once-glassy water just off of Gainesville’s Holly Park was our racetrack this Sunday afternoon. Hollis invited me along while he tested his big boat for this weekend’s American Power Boat Association offshore race in Islamorada, Fla.

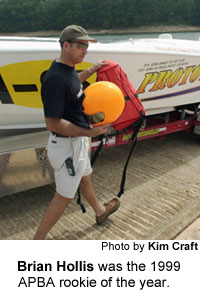

This is not the same boat Hollis drove to the APBA southeastern high points championship last year. It is not the boat on which he became the circuit’s driver and rookie of the year. No, he ditched that boat in March, two weeks before the 2000 racing season began.

This is a brand new boat, with less than 24 hours of running time under its hood. The purple and orange detailing on its shiny white hull looks as if it were painted yesterday.

This is a brand new boat, with less than 24 hours of running time under its hood. The purple and orange detailing on its shiny white hull looks as if it were painted yesterday.

Hollis not only owns this boat, he owns the company that built it — prototypeboats.com, based in Gainesville. He now sells to the public the very same boats he races, with the motto, “Race on Sunday, sell on Monday.”

The switch from driver to manufacturer/driver has made it impossible for Hollis to repeat the remarkable success of his rookie racing season. He began the season with no boat, and is still working the kinks out of his new one.

“But you watch in 2001,” warned Hollis, 36. “We’re going to kick (butt).”

I believed him. Of course, at that moment I would have agreed with anything Hollis told me. My life was in his hands. He sat behind the wheel of his Prototype Factory 1 offshore racer. And I sat beside him.

The bucket seats are a tight fit … with good reason.

“Yeah, you want to stay in them,” Hollis said knowingly. “I’ve been thrown out a couple times.”

Hollis’ most recent ejection came last November at the world championships in St. Petersburg, Fla. As luck would have it, it was the first race attended by Hollis’ parents, who were already quite wary of their son’s new profession.

“We hooked the turn,” Hollis remembered. “We did a complete 180 degrees.”

No seat belts in these boats. It would be too unsafe if the boat were to flip.

No brakes, either. That’s why the throttle man is so important. That’s why I wasn’t sure if I should be the throttle man. But I was.

“OK, whenever you’re ready, Dan,” I heard in my ear. Hollis and I communicated through speakers in our helmets.

With my right hand, I nudged the throttle forward slightly. The boat turned up its nose and began to move faster. But not fast enough.

“Open her up,” Hollis instructed. “All the way.”

I paused, and then pushed the throttle forward — all the way. The boat jumped, and picked up speed quickly. Soon we were traveling at nearly 75 mph.

Now, I know what you’re thinking. Bass boats can hit 75 mph, so what’s the big deal? Well, bass boats aren’t pulling 4,000 pounds like these Factory 1 racers are.

I could feel the power. It was all in my right hand.

And the wind was directly in my face. My head, made heavier by the helmet, became difficult to turn from side to side. The rest of my body was tense.

Beside me, his hands stuck tight to the wheel, it was all Hollis could do to keep the boat going straight. At high speeds, a very small portion of the hull actually occupies water, therefore the driver must constantly counter-steer and adjust to keep the craft from veering off course.

Now, imagine doing all of this in a race, with boats so close beside you that you can touch them. Imagine not knowing how many of the 20 boats that started the race will make it through the first turn 3.5 miles ahead. Imagine traveling in excess of 80 mph, seven laps around a 10-mile course, all the while dodging freighters, sea turtles and six-foot swells.

That’s offshore power boat racing.

“It’s just like NASCAR, only we play on the water,” said 38-year-old Pat Bihary, one of several locals that Hollis has gotten hooked on offshore racing.

“It’s the need for speed. And the water is constantly changing. When we make a lap, the next lap is gonna be different. It’s you against the water.”

By the way, if it’s Bihary against the water, I’m betting on Bihary. I took a ride in his 38-foot, 1,000-horsepower twin-engine monster. And, wow!

The APBA promotes offshore racing as “America’s next great motorsport.” While the sport has a dedicated fan base, including the occasional groupie, it’s a few laps behind some of its land-based counterparts. Even the driver of the year has trouble finding sponsors, Hollis said.

So offshore racing continues to be a labor of love, and money. Hollis scrapped plans to build a Lake Lanier home when he decided to get into the sport. He sold some of his possessions. He dipped into his savings.

“You’ve got to give up something if you’re going to do it,” Hollis said. “You can’t have it all. But I just love boats, man.”