August 1, 2000 — First came the idea. Then the plan.

Training followed. Equipment was purchased along the way.

And now, finally, the time has come.

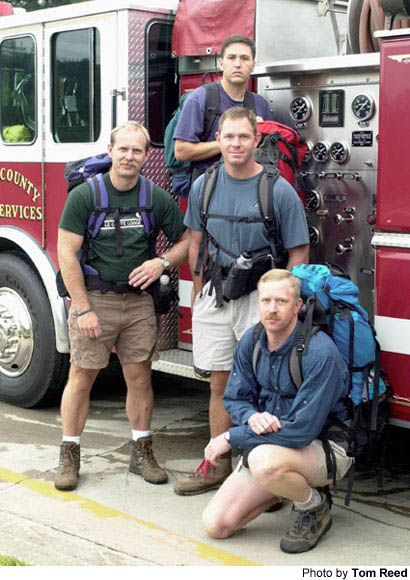

It was more than a year ago when Hall County firefighters Bryan Cash, Tyler Dorsey, Todd Folger and Milton Keller decided they wanted to climb Mount Rainier in Washington.

The nerve was summoned long ago. But the nerves never went away.

“It’s starting to worry me a little bit, to be honest with you,” Cash said to me over the phone late last week.

He was sitting in his station house, reading and re-reading a printout from the Rainier Mountaineering, Inc. website.

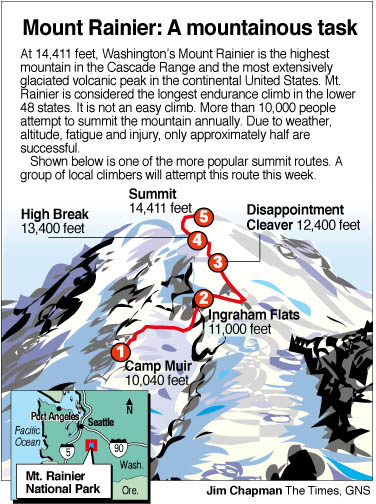

“Mt. Rainier is considered the longest endurance climb in the lower 48 states,” Cash read to me. “It is imperative to undertake a rigorous conditioning program …”

He scanned ahead to the last sentence: “You simply cannot over-train for this trip.”

Cash, like the rest of his climbing crew, began training for Rainier in March. He’s hiked and jogged. He’s climbed stairs and lifted weights. He’s shed 53 pounds.

“I don’t know if I’ve really done enough,” said Cash, 29, who now weighs 165 pounds. “But I’m ready. We’ll try it. That’s all you can do, I guess.”

Monday night the group flew into Seattle. And sometime after daybreak today, they likely got their first glimpse of Rainier. It’s always there, off in the distance, watching over the Emerald City. For adventure seekers, its lure is inescapable.

At 14,411 feet, Mt. Rainier is the highest mountain in the Cascade Range. It is surrounded by the largest single-mountain glacier system in the continental United States. It is also a dormant volcano.

To many, Rainier is the closest they will ever come to climbing a Himalayan peak. By Friday, four Hall County firefighters hope to be standing atop it.

But it won’t be easy. Every year, more than 10,000 people try to reach Rainier’s summit. Approximately half of them fail.

Weather is severe on the mountain. Avalanches can occur at any time. And air is thin. At 12,000 feet, bodies receive roughly half the oxygen they do at sea level.

Fatalities are statistically rare, but not uncommon. Since 1855, an estimated 88 people have died on the mountain. Forty-seven of the deaths occurred in the last 20 years.

But firefighters risk their lives for a living.

I met up with Dorsey, Folger and Keller 10 days ago for one of their final training hikes before the big trip. We hiked along the Appalachian Trail, from Unicoi Gap to Rocky Mountain, and talked about Rainier.

“I think cardiovascularly we’ll be fine,” said Dorsey, 30. “The elevation is the only thing we don’t know about. That’s going to be the unknown.”

No one in the group has hiked above Mount LeConte in the Great Smoky Mountains. At 6,593 feet, LeConte is only about 1,000 feet higher than the elevation of the Paradise Guide House on Rainier — the spot from which groups begin their ascent of the mountain.

With higher elevations come lower temperatures, another thing that’s hard to simulate in the Southeast. Temperatures below freezing are the norm on Rainier. We drove past thermometers reading 97 degrees on our way to Unicoi Gap.

“We try to come up here at least once a week,” said Folger, 30. “It’s pretty steep right from the highway to the top of the mountain.”

We began to sweat immediately on the trail, heat and heavy packs saw to that. A Rainier summit attempt requires a lot of gear. For months the firefighters have been adding weight to their packs to prepare for the load.

I filled mine with 40 pounds of barbell weights. Folger had a large sack of dog food in his. On Rainier he’ll have nearly $2,000 worth of equipment instead.

And on Rainier, the path of roots, rock and dirt will be replaced by ice, snow and crevasses 1,000 feet deep. But the group will be the same. And for these four firefighters that’s all that matters.

Keller is a captain, Dorsey a lieutenant, Folger a paramedic and Cash an engineer. They’re all trained emergency medical technicians. They’re all trained to save lives.

And they all used to work at the same station, 24 hours at a time.

“We’re like brothers,” said Keller, 40. “We know each other’s strengths and weaknesses as well as our closest family members. I think that gives us an advantage starting out.”

“And we know that none of us will quit,” Dorsey added. “We know that if somebody can’t make it, there’s a reason. They will have pushed themselves until they couldn’t go any further. We’ve been in some very close calls together.”

“Any specific close calls come to mind?” I asked.

“Basically everything we do is a close call,” Dorsey responded. “It’s a lot of skill and a lot of knowledge — and a lot of luck.”

They will need all three to get to the top of Mt. Rainier.