July 9, 2000 — It was a typical Friday morning.

I struck out Ken Griffey Jr., got struck out by Greg Maddux and received a knuckleball lesson from Phil Niekro.

Yep, pretty routine. Just another day at the Major League Baseball All-Star FanFest, which runs through Tuesday at the Georgia World Congress Center in Atlanta.

Granted, Junior and Maddux were mere images on a video screen. The real Greg Maddux wouldn’t have allowed my two foul tips. The real Ken Griffey Jr. would have tagged, not taken, my 60 mph “fastball.”

But Niekro was real. He always is.

Sure, the longtime Atlanta Brave is a Hall of Famer, the 14th winningest pitcher in Major League Baseball history. But Niekro, a 13-year resident of Flowery Branch, is always willing to stop and chat. Especially about baseball. Particularly about the knuckleball, the pitch that allowed him to last 24 years in the majors and win 318 games.

“If it wasn’t for the knuckleball, I’d probably be working in the coal mines somewhere back in Ohio,” Niekro said. He was serious.

At 61, Niekro is tanned, fit and trim — and far away from the Appalachian foothills of eastern Ohio. He fishes on Lake Lanier almost daily. He has been known to frequent Mountain Man Barbeque on Atlanta Highway. He says he still gets out and throws from time to time.

Not a bad post-retirement regimen.

But not this week. The All-Star Game is in Atlanta for the first time since 1972. And Niekro, the FanFest’s official spokesman, is playing a major role.

He was signing baseballs in a back room when I was ushered in to speak with him. Graciously, he put the pen down and stood up. He has a way of making you feel important — as if I was the only writer he would talk to that day, as if he’d never before fielded questions about the knuckleball.

The idea, I had discussed with several public relations contacts in the weeks leading up to this meeting, was to get a knuckleball lesson from old Knucksie himself. Niekro politely opted out.

“I don’t know how I could teach you in a day,” Niekro said. “You know, it took me years. I was in grade school when I started learning that pitch, and I was still learning when I quit playing.”

Niekro learned the knuckleball from his father, a coal miner who used the pitch successfully in the industrial leagues around Bridgeport, Ohio.

“When I was old enough to start playing catch and grip a ball, he showed me how to do it,” Niekro said. “And the rest is history.”

The then Milwaukee Braves signed Niekro and his knuckleball out of high school. He worked his way up through the minors and made the big leagues to stay in 1965. Soon he was the ace of the Braves staff. In 1969, he won 23 games and led Atlanta to the first National League West title.

In 1973, Niekro pitched a no-hitter, the first by a Braves pitcher since Warren Spahn recorded one in 1961. He was a five-time All-Star and Gold Glover and was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1997.

“Could you at least show me how you hold the ball?” I asked, having thrown my own bastardized knuckler to friends for years.

“I could show you how to hold it, yeah,” Niekro responded, reaching for a nearby ball. “Then you have to go home in the backyard and throw it and throw it, week after week, month after month, year after year.”

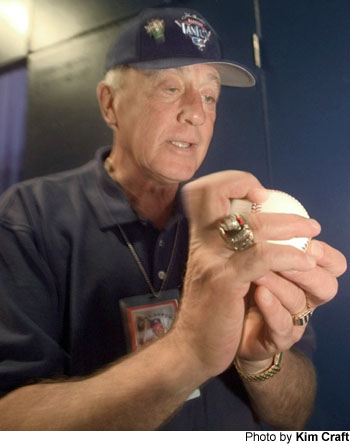

He took the ball in his right hand and dug the nails of his index and middle fingers into the white leather, as far away as possible from the red seams.

“That’s basically it, right there,” he said. “Grip it firm and tight and these two fingers come up and dig into the ball right here.”

The delivery, Niekro said, is where most people run into problems. Unlike other pitches, the wrist remains locked when throwing the knuckleball. Ideally, ball leaves hand with no spin at all.

“It never does the same thing twice,” said Niekro who, thanks to the knuckleball’s unpredictability, owns the National League record for wild pitches with 200. “I’m not making this thing do anything. It’s on its own. But it will do more than any other pitch you throw. And why it works like that, I have no idea.”

With a laugh, Niekro told me his knucklers approached the plate anywhere between 30 and 70 mph. I asked how that compared to his fastball.

“Wind behind me or in front of me?” Niekro asked with a wink. “I didn’t throw hard.”

And that is exactly why Niekro, who retired at the age of 48, stuck around so long. He never threw hard enough to get a sore arm. He was durable. He is tied with Cy Young for the most 200-plus inning seasons at 19. He won 121 games after age 40, the most in baseball history.

“I was able to go out there every five days for 23 years in the big leagues,” Niekro said. “When you can do that, you have a chance to win a lot of ballgames, which I did. I lost a lot of ballgames, too.”

Two hundred seventy-four to be exact. The most by a National League pitcher in the modern era. In 49 of those losses, Niekro’s team failed to score a single run. Playing for the Braves, perennial also-rans during the 1970s, helped Niekro achieve another dubious distinction. His 24 seasons without a World Series appearance is a major league record.

My conversation and clinic with Niekro ended abruptly. He was informed that he had official spokesman duties to attend to. A sincere smile and a handshake and Knucksie was off.

So was I. Back home, I broke out the old ball and glove, dug my fingernails in and started throwing.

I think I might have some good years left in me.