July 4, 2000 — Right now, somewhere in Lake Lanier, two gar are likely reminiscing about the species’ halcyon days: the 50 million or so years before Jack Barnett started fishing.

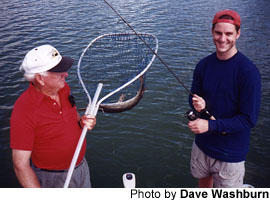

And right now, somewhere on Lake Lanier, Barnett is likely on his pontoon boat, reeling in one of these ponderous prehistoric predators, laughing.

Gar’s luck began to run out when Barnett first focused on the fish some 20 years ago. Along the Georgia coast’s Sapelo Sound, Barnett, then in his 50s, began angling for gar with a spear, and then a bow and arrow. A few years later, he heard of people landing gar using a simple braided nylon rope.

Gar’s luck began to run out when Barnett first focused on the fish some 20 years ago. Along the Georgia coast’s Sapelo Sound, Barnett, then in his 50s, began angling for gar with a spear, and then a bow and arrow. A few years later, he heard of people landing gar using a simple braided nylon rope.

He tried it, and it worked.

“I’ve been doing it ever since,” said Barnett, now 73, as he led me to the boat dock behind his lakeside home in northern Hall County. He stopped in mid-stride, turned around, smiled foxily and added, “I just kind of perfected it a little bit.”

The result is Jack Barnett’s Original Gar Lure. Perhaps you’ve spotted it in area sporting goods shops. Perhaps you’ve stared at it incredulously.

There are no hooks in Barnett’s gar lure, none at all. Just a small, painted lead fish head followed by a length of combed out nylon rope. That’s it.

Barnett often seems amused by the simplicity of his invention. He caught me inspecting a lure skeptically. “It looks good in the water,” he said with a quick chuckle.

The gar agree. I boated my first one in less than 20 minutes, and the only thing hooked was me.

The longnose gar’s already elongated body is stretched out even further by its protracted and pointy bill, which houses long rows of needlelike teeth.

The longnose gar’s already elongated body is stretched out even further by its protracted and pointy bill, which houses long rows of needlelike teeth.

Once a gar strikes the lure, there’s no escape.

“You don’t have to jerk it or anything,” said Barnett, who retired from the printing industry in 1988.

“Because there’s no hook to set. They either got it or they don’t.”

The result is a twist of teeth and twine almost impossible to untangle — unless you have another of Barnett’s inventions handy. The “gar-jack,” as Barnett likes to call it, is a doctored plank of wood that, along with a pair of pliers and a “tooth spreader,” makes the extrication process a relatively painless one.

Painless, of course, only if the gar’s sharp teeth don’t come in contact with your skin. That has happened to Barnett often, and he has the scars to prove it. He calls those marks “gar-bitis.”

Not even ten minutes passed before my rod tip doubled over again. The hit was unmistakable. This one was bigger. It was obvious.

I battled the fish to the surface. It glanced at me pugnaciously through a beady yellow eye. Then it disappeared. Line screamed off my open-face spinning rod.

I battled the fish to the surface. It glanced at me pugnaciously through a beady yellow eye. Then it disappeared. Line screamed off my open-face spinning rod.

I settled myself and smiled. The fight was on.

I won, of course. Barnett’s lure saw to that. But this gar didn’t seem familiar with Barnett’s work or of the inevitable outcome. He made me sweat for it.

Here’s the tale of the tape. My opponent measured about 3.5 feet long and weighed in at approximately nine pounds. Its body was encased in an armor of thick, diamond-shaped scales. Its teeth were several and sharp.

I, although not quite as intimidating, enjoyed a definite reach advantage. Gar don’t have arms.

Thus far, an overcast sky and a steady sprinkle of rain accompanied us on our trip.

“If this was a good hot day,” Barnett said, “we’d be catching the tar out of them.”

Two gar in 30 minutes is nothing during optimum conditions, according to Barnett. When the sun is high and the water still, you can see them basking in shallow, open water like logs.

“The ideal situation is to find a whole lot of them just under the surface,” explained Barnett, who said the best months for gar fishing are June through September. “You can see them, and you can just kind of pick out the one you want.”

Because of the cloudy skies and ripply water, we cast blind into Barnett’s favorite spots on Lanier last week. Often we’d see a gar create a boil on the water’s surface. Interestingly, these odd fish regularly take in gulps of atmospheric air.

Because of the cloudy skies and ripply water, we cast blind into Barnett’s favorite spots on Lanier last week. Often we’d see a gar create a boil on the water’s surface. Interestingly, these odd fish regularly take in gulps of atmospheric air.

Some call gar a nuisance. They have voracious appetites and are predators from birth. Some call gar trash. There are no size or keep limits for gar on Lanier.

“A lot of people say how ugly they are, but they’re neat to me,” said Barnett, who caught his biggest gar — 56 inches, 26 pounds — two years ago. “They hit hard, they pull hard, they jump, they fight and they’re good to eat. Now, what else do you want?”

Yes, Barnett said gar is good to eat. He grills it, fries it, even boils it.

“They don’t have any fish taste to them,” he said. “It’s unreal. I don’t know what they taste like.”

He laughed, then added, “Taste like chicken, I guess.”

Eventually the clouds broke, the rain ceased and the sun made its first appearance of the afternoon. This was drought season, after all.

I caught another one, but after that it was all Barnett, the lure man himself.

And he caught the tar out of them.