June 13, 2000 — Hiking up Trail 427 in Montana’s Gallatin National Forest is one colossal internal struggle.

The instinct toward self preservation demands that you watch your step. The trail can be rocky and wet, steep and snowy.

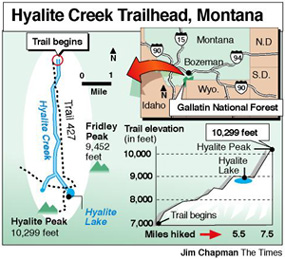

But a force more powerful draws your eyes upward. Eleven waterfalls line the 5.5-mile trail that bobs and weaves along Hyalite Creek, climbs more than 1,800 feet through the subalpine Hyalite Basin and eventually leads you to the wide mountainous bowl that holds Hyalite Lake some 8,900 feet above sea level.

But a force more powerful draws your eyes upward. Eleven waterfalls line the 5.5-mile trail that bobs and weaves along Hyalite Creek, climbs more than 1,800 feet through the subalpine Hyalite Basin and eventually leads you to the wide mountainous bowl that holds Hyalite Lake some 8,900 feet above sea level.

So there’s the trade-off. Risk the occasional stumble or fall and march face first into the living, breathing postcard that is the Rocky Mountains of southwest Montana. Or memorize the stitching in your climbing boots.

For me the decision was easy. My scrapes and bruises will go away. But the movies of Montana that play in my mind will be there for the rest of my life.

The guidebook warned that winter in the Hyalite Basin can last into July. But temperatures in nearby Bozeman, Mont. were hitting the mid-80s during this first week of June. So my friends — high school buddies Justin, of Bozeman, and Brian, of Atlanta — and I packed up our camping gear and headed south to the Gallatin Range of the Rockies.

Well, the guidebook was right. A mile into the hike, patches of snow began to dot the landscape of dirt, gravel and grass. Another mile, and patches of dirt, gravel and grass began to dot the landscape of snow.

Well, the guidebook was right. A mile into the hike, patches of snow began to dot the landscape of dirt, gravel and grass. Another mile, and patches of dirt, gravel and grass began to dot the landscape of snow.

Soon our path was a cushion of white, garnished with a forest of towering evergreens and surrounded by ridges of red-rocked, snow-capped mountains.

The weather was warm and sunny. And here we were sweating, wearing shorts and T-shirts, trudging through knee-high drifts of snow — in June.

“What do you think are the odds of us running into another person today?” Justin asked early in the hike.

“Zero would be just fine with me,” Brian responded.

To our surprise, there were a few scattered hikers along the trail. But as we got higher, as Hyalite Lake became nearer, there were fewer and fewer. Until there were none.

The final mile was the toughest. By that time we had lost the trail and were following the faint footprints previous hikers had left in the snow. Ours wasn’t the prescribed path, but we knew we were headed in the right direction — up.

The climb was long, slippery and steep. Air became thin. Breathing became difficult. Thirty-pound packs became heavier.

My head started to hurt. I needed a break — often. Water was never more welcome. Oranges never tasted so good.

After four hours of hiking, we were there. Fridley Peak stood tall to the east, Hyalite Peak to the west. Hyalite Lake sat before us. It was frozen.

Snow covered all. It was hard to keep our eyes open.

We dropped our packs and sat for a while, but Hyalite Peak — 1,400 more feet above — loomed large in our horizon. We knew we had to get to the top of that mountain.

For that we had no path, no footprints to follow. We scrambled up snow and loose rock, hoping that a bigger rock or the odd evergreen would stop us should we begin to slide down the mountainside.

My knee hurt. My hands were numb. But the view that awaited us soothed all. Green, red and white, the Hyalite Basin flowed north into forever.

We scampered, sometimes slid, back down the peak to where our gear lay. We scouted out a dry patch of land under a large pine tree and set up camp.

With the campfire burning, Hyalite Creek flowing in the distance and not another soul within miles, we sat there and watched the stars — one by one — fill the darkening sky above the very peak we climbed just hours earlier.

With the campfire burning, Hyalite Creek flowing in the distance and not another soul within miles, we sat there and watched the stars — one by one — fill the darkening sky above the very peak we climbed just hours earlier.

It was that image, that movie, that played in my mind on Saturday. I was standing in the crowded train at the Atlanta airport. The air was stale. The people were loud. Someone blocked the door and the train sat still for minutes.

I closed my eyes and dreamed about mountains.