February 29, 2000 — The scars tell the story of the toughest battle of David Monroe’s life.

They dot his abdomen. They serve as a constant reminder of the disease that wreaked havoc on the 56-year-old’s insides for eight long years.

Colitis cost Monroe his colon just over a year ago — it nearly cost him his life, too.

But the Gainesville martial arts instructor is a fighter. Always has been.

He clobbered colitis, and today looks younger and more fit than most men 20 years his junior.

Monroe didn’t do it alone, however. And he considers his practice of tai chi — the ancient Asian regimen known as “moving meditation” — to be a main reason why he was able to sustain through the toughest of times.

“It gave me focus,” Monroe told me. “It made me realize that I was still blessed, that I was still alive and well.”

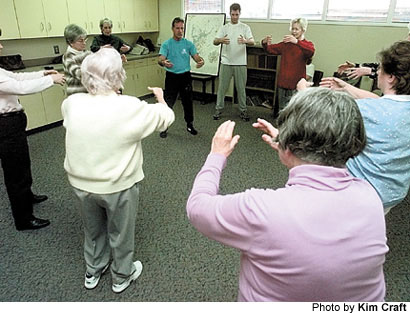

Every Monday morning, several middle-aged and elderly women — and occasionally the odd newspaper writer — arrive at Monroe’s tai chi class at the Hall County Senior Center looking for that same focus.

They want to soothe their aching knees and hips. They want to improve their balance and flexibility. They want to feel better about themselves, inside and out.

Sixty-two-year-old Patti Hallowell has taken the class for more than a year.

“It has improved my sense of balance greatly,” said Hallowell, of Gainesville, whose career as a flight attendant was cut short by an inner-ear problem that affected her sense of equilibrium.

“I’ve tried karate and yoga in the past. Now that I’m older, this is an easier exercise to do. It’s easy on the joints and I know that it’s very beneficial.”

According to several medical studies, tai chi’s most striking beneficial effects are on posture, strength and balance. Regular tai chi training by the elderly has also been shown to greatly reduce the risk of falling — one of the major causes of serious injury among older men and women.

“Every MD in the United States of America knows that this is true, and they are now prescribing tai chi to an awful lot of people,” Monroe said.

When done correctly, tai chi’s movements are so graceful and fluid it seems its beauty alone would be therapeutic. But there is much more to it than simple aesthetics.

Tai chi practitioners are in search of attaining a perfect balance between body, mind and soul. When everything comes together — each deep and cleansing breath, each slow and deliberate movement — a harmonious flow of energy is said to overtake the body.

“The more you do it,” said Hallowell, “the more you can feel it, and the more you can feel the benefits that you’re getting from it.

“It takes time. Because at first, you’re so concerned about what this foot is supposed to be doing or what this hand is supposed to be doing.”

That describes the boat that I believe many of us found ourselves in. As Monroe glided balletically across the floor before us — “waving hands like cloud” and “spreading wings like crane” — we tottered along rigidly, trying to follow suit.

I don’t think I ever got it.

So when Monroe would ask us to feel water coming out of our fingers, energy passing between our hands, or strings pulling at our arms, I would simply raise an eyebrow … and try to remember to breath.

Yes, tai chi takes time.

Monroe didn’t take up take up tai chi until seven years ago. Before then he dedicated his time to more brutal and intense martial arts. He continues to teach classes in what he calls “practical self defense,” which incorporates several different martial arts disciplines.

“But tai chi for me is the core,” said Monroe, quick to point out that tai chi itself is a deadly martial art. After class he spread his wings like crane at full speed and knocked me to the ground.

I doubt the women at the senior center are aware of tai chi’s pernicious possibilities. I doubt if they care. They just want their hips and knees to feel better. They are there for tai chi’s healing potential.

And who better to teach them about that than Monroe?

“It’s proven itself to me,” he said, placing his hand over his abdomen.