February 22, 2000 — The ball didn’t bounce.

It just stayed there, on the floor, and slowly dribbled away.

I scratched my head and thought, “Well, that’s weird.”

Ball is round. Floor is flat. Ball should bounce. Right?

Wrong. That would be too easy. And, as I learned last week at the Concourse Athletic Club in Atlanta, nothing is easy about squash.

My preconceived notions of the sport were wrong — as preconceived notions typically are.

I thought squash was an elitist sport, the fancy of Ivy League types with argyle socks, Saab convertibles and fake British accents. I thought it was simply racquetball with a smaller ball, a longer racket and a bigger ego.

True, the squash inner circle is still an exclusive club, especially in the U.S., where the sport has a way to go to match its popularity overseas. Outside of large metropolitan areas stateside, places to play are few — and often expensive. My 1990 Toyota Corolla stuck out sorely among the shiny new cars — a few Saab convertibles among them —Êparked at the pricey Concourse club.

But if squash players tend to be a bit on the wealthy side, they are very physically fit wealthy people.

My legs ached for days after my lesson.

“Racquetball is a woman’s sport,” said Concourse’s squash pro Andre Maur, not one to censor his thoughts. “That’s what it is. The better you play racquetball, the shorter your rallies are. You’re waiting, waiting, waiting. You can have a pint of Guinness in between rallies. That’s how slow it is.”

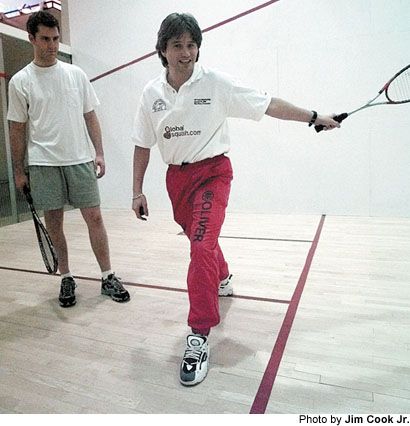

Maur’s Irish accent is very real. He spent his formative years in Dublin before embarking on a highly successful professional squash career that at times saw him ranked in the top-10 in Ireland and Germany.

Thirty-five and retired from the world circuit, Maur now focuses his energies on coaching and promoting tournaments around the globe. In April, Maur is bringing to the Concourse the Atlanta Open, which with more than 200 participants, is expected to be the biggest squash tournament ever in the Atlanta area.

The guy can still play, too. In tournaments last December, Maur won both the U.S. Masters and Irish Senior titles.

“In squash, you can’t afford to wait,” Maur continued. “You’re always constantly moving.”

And for that you can thank that darn little ball. No bigger than a Ping-Pong ball and made of a soft, malleable rubber, the ball doesn’t come to you. You have to come to it. Quickly. Constantly.

“Right-e-o. So you want to have a hit?” Maur said with a crooked smile.

Maur was intent on getting the never-say-stop pace of his sport across to me. I had planned on asking Maur to play a couple games, but after five minutes on the court I realized that wouldn’t have been much fun for either of us. So did Maur.

“You wouldn’t get anything out of it,” Maur said matter-of-factly. “It’s a terrible thing to say, but you would just be picking the ball up off of the ground most of the time. It’s best to start off with the basics.”

So we did. Backhands and forehands. That was it. That was enough.

Since squash is a sport of constant movement, Maur had me in constant motion. Running forward toward the side wall to strike the ball, and back to center court to await the next hit. Back and forth. Again and again.

Ideally, steps in squash are big and low to the ground. For right-handed players, the last step before a forehand is a long lunge with the left leg. Once the ball is struck, you push off with that same leg to send you back to mid-court. These are actions you feel the next morning … and the next.

Ideally, the forehand stroke is a sweeping one, with a long backswing and a pronounced follow-through. If hit soundly enough, that squishy little ball can zip around at quite a rapid pace.

Ideally, I would have caught on right away. Ideally.

“No chicken steps, Dan,” Maur would yell. My legs, he said, were “wooden.”

My body was not low enough. My lunges were not long enough. My backswing did not swing back far enough. And often after striking the ball, my momentum sent me crashing into the wall, not back toward the center of the court.

Perhaps my biggest fault — especially in the eyes of Maur — was my habit of resting my racket in my left hand in between strokes. You don’t use your off arm in squash.

“That’s your pint-of-Guinness arm,” said Maur, admittedly no stranger to the dark and creamy beverage. “Put your left arm behind your back. You don’t need your left arm.”

Yes, I was a mess, but a sweaty mess.

“You see how strenuous it is, Dan,” Maur said as I gasped for air. “I don’t know if the A/C is on or if you’re just breathing that hard.”

After the backhand part of my lesson — which was even less of an aesthetic success — I believe Maur must have felt he was inside a wind tunnel. I was breathing that hard.

Squash is definitely not the sport of the mollycoddled.

“Look, you’re sweating your you-know-what off,” Maur said after my 30-minute lesson. “And this was basically a warm-up session. But at least you were connecting with the ball. That is the main thing at the moment.”

The main thing, perhaps. But not the only thing.

I walked to the parking garage, past the Saabs and the Benzes, and squeezed my sore legs into my Corolla. I was headed home with one thing on my mind.

All this talk of beer made me thirsty.

I needed a pint of Guinness.