December 7, 1999 — “You’re in pretty bad shape there,” Jim Jennings said to me matter-of-factly.

He was describing the predicament that lay before me on the green felt of his pool table.

He could have just as easily been describing my somewhat larger problem at the time: I was playing pool with Jim Jennings, one of the best nine-ball players in Georgia, and I was playing him in the den of his Gainesville home on his own personal table — not that a neutral table would have had any impact on the ineveitable outcome.

“In the state of Georgia Jim is at least in the top four to five players,” said Andy Anderson, a local billiards junkie who is opening an upscale pool hall in Baldwin next month. “And in our immediate area he is the player.”

Jennings is the type of pool player you can’t afford to make mistakes against, the type of player I try to avoid. Because making mistakes is a big part of my game.

But my current plight, a jumble of little numbered balls atop a slate table, was not caused by an error on my part. Jennings had snookered me. He had snookered me good. And there was nothing I could do about it.

I needed to somehow knock the cue ball into the one, but the angles just weren’t there. Jennings made sure of that. He had played it safe, setting me up for failure.

Just three shots into the game, I was already on the verge of committing my second foul. One more and I would lose … again. I had only been in Jennings’ den about 20 minutes and I was already down three games to none.

My previous three losses, however, had been of the traditional variety: Jennings knocking all of the balls in in order. At least this time he was mixing things up, showing me there were other ways I could lose, as well.

I fouled the shot.

Jennings chalked up his cue and eyeballed the table. “Now, what we do here is,” Jennings said as he prepared to “three foul” me. “You’re not going to like this.”

He was right. Jennings stroked the cue ball in to the one. The one glanced against a side rail and the cue ball drifted the other way, settling behind a barricade of balls.

He cornered me. He snookered me. He hooked me. Call it what you like.

“You just lost the game,” Jennings said with a smile.

And just like that I was down 4-0.

Not that I expected anything else playing against a player of Jennings’ caliber. Jennings, 51, a paint contractor from Gainesville, has been a regular on the regional tournament scene for more than a decade. He’s won his fair share of titles and $1,000 purses, too.

In September, he traveled to Chesapeake, Virginia for the $30,000 U.S. Open, which with 256 competitiors is the biggest tournament in the world. He didn’t win, but he got to go up against the sport’s best. That alone was worth the $500 entry fee.

“Where else can you get to play all of these great players?” said Jennings, who had billiards in his blood from a young age — his father, Wallace, of Forest Park, once beat the legendary Minnesota Fats in a snooker tournament in Macon.

“And I have beaten some of the top players in tournaments. When I get in stroke, what you would call the zone, I run out just as good as they do. But I don’t hold it as long, and I’m going to make little mistakes that they don’t. That’s all it takes.”

I’m not sure if Jennings officially entered the zone while we were playing (frankly, he didn’t need to), but he’s the best I’ve ever seen in person.

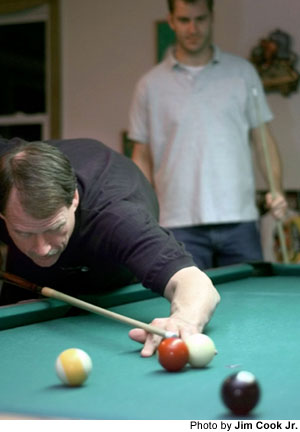

He’s a big guy, probably 6-foot-4 at least, and he spreads his long legs out wide when he bends down to shoot. His stroke is smooth and forceful; his strong forearm swings like a catapult beneath his still elbow.

And when Jennings is running the table, he is a machine. He shoots. He chalks. He walks. Shoot. Chalk. Walk. The numbered balls fall into the pockets in order. The cue ball, as if guided by a string, drifts into perfect position for the next shot.

And Jennings does this in a surprisingly quick, business-like manner. He doesn’t overthink his shots. The angles, the english, the draw, it’s all second-nature to him. He’s been in almost any situation before.

Now, I on the other hand, haven’t. Most of my pool experience is of the eight-ball variety, where, unlike nine ball, you usually have more than one ball you can shoot at.

So against Jennings I spent a good bit of time scratching my head, squinting and circling the table. And in the end, after all of my analysis, I realized I still had no idea how to attempt my impending shot.

“Gets your old brain a hurtin’, doesn’t it?” Jennings chuckled. “You know, good players think three balls ahead.”

I had enough trouble worrying about one ball. Early on I showed a knack for knocking in what Jennings called “slop,” a ball other than the one I was aiming for. And if the slop occurs after the cue ball collides with the proper ball, it counts.

Slop, however, doesn’t get you very far. I was now down 7-0.

Then Jennings’ wife Cathy offered some advice from the living room, “Make him play you left-handed, Dan. That’s a fairer game.”

By this point I had little pride left, so I took Cathy’s advice. And it wasn’t long before I was overanalyzing a possible game-winning shot. I sank it, knocked the nine ball right in. Of course, I knocked the cue ball in too. I lost … again.

“One more?” I asked.

Jim obliged.

I knocked one in on the break and slopped in some more after that. Soon I was staring at a familiar situation. Nothing else on the table but the cue ball, the nine ball and a chance for redemption.

I got down low and lined up the shot. Straight back. Follow through.

Nine ball, corner pocket. No scratch this time.

“Nice shot,” Jim said. “Wanna play again?”

“No thanks.”

A good slop player knows when it’s time to quit.