November 16, 1999 — Imagine teeing off with Tiger Woods, going one-on-one with Michael Jordan, shagging flies with Ken Griffey Jr.

Pretty cool, right?

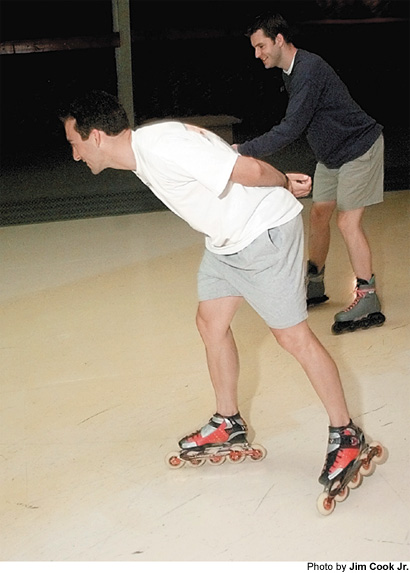

Well, I went inline roller skating with Derek Downing. And if you were from Bogota, Colombia you would be drooling right now. Trust me.

Derek, a 26-year-old Forsyth Central High graduate, has been one of the top two inline skaters in the world since turning pro in 1992.

Pro? Yes, pro. There are approximately 150 professional inline skaters worldwide, and in places like Colombia, Switzerland and Chile they are treated like heroes.

Derek — who competes in events ranging from 300-meter sprints to 84-kilometer double marathons — has nine world titles to his name. He won seven gold medals at the 1997 Pan Am Games in Ecuador. He has two gold medals from ESPN’s Extreme Games.

Those feats likely seemed easy compared to his task last week — getting me up and moving on skates.

“So you really have never skated before,” Derek said, looking at me, chuckling.

The moment I first stood up on my inline skates my ankles collapsed inward and my knees knocked into one another. No, I had never tried inline skating before. And now it was painfully obvious.

I had skated the old-fashioned way in my youth. We used the lace-up rental skates at our local rink, the ones with four big fluorescent orange wheels that made your feet look like monster trucks, the ones that skating people like Derek refer to as “quads.”

I was never any good using those skates, either. I could get going OK, but stopping was an issue. Instead of using the brakes on my skates I used the walls of the rink. Not very graceful.

I scoped out the walls of the Cumming Skate Center, owned by Derek’s family. Ouch.

But stopping didn’t seem like it was going to be a problem for me with inline skates, because I was having enough trouble getting moving.

My skates and the floor collided loudly with every step I took. Every muscle in my body was tense, concentrating on not falling down. I felt quite awkward.

“It’s really not that bad,” Derek said, trying to keep down with my plodding pace. “Just push side to side as if you were ice skating. Try to stay on top of the wheels and bend your legs a little.”

“Why don’t you show me how it’s done,” I said.

“OK.”

And Derek was off.

Derek’s speed sneaks up on you. His motions, fluid and methodical, seem incongruous with his accelerated pace. It is as though he is moving in place, while the rink itself whizzes around and around.

It’s easy to be hypnotized by Derek — foot over foot, arm passing back and forth — but then, before you know it, he’s speeding past you again.

A few more passes and Derek was back by my side, moving as deliberately as I. I’m sure he felt as if he were standing still.

Our pace gradually picked up, and as we skated around the rink we discussed how Derek came to be one of the highest-paid inline skaters (“very close” to six figures annually, Derek said) in the sport’s short history .

The process started early. Derek’s parents, David and Diane, third-generation skating people, had him in skates before he could walk. Soon he was traveling the country racing on quad skates.

Now he travels the world racing on inline skates (very expensive inline skates — Derek’s custom-made Verduccis are $1,500). Inlines, introduced to competition in the early 1990s, are much faster than quads — Derek has hit an amazing 64 mph on downhill races — and have allowed the sport to take off in popularity around the world, especially South America and Europe.

That keeps Derek a busy man. As a member of Team Verducci he is on the road about half the year. And when he’s not competing, he’s training. Derek skates more than 150-miles a week.

“That’s the sad part about it,” said Derek, who now lives in Suwanee. “You put all of this time into it and the sport’s just not very big in the U.S.”

That’s certainly not the case in other countries, where Derek’s image is plastered on vans, where Derek and his teammates have armed guards escort them from place to place.

The most recognition Derek got stateside came after he took the gold in the inaugural Extreme Games downhill competition in 1995.

“I think I got a couple free oil changes from people who recognized me, but that was it,” laughed Downing, who married his wife Emily in July. “It’s actually nice to come home and relax and not have to deal with anything …

“Hey, you’re doing pretty good on those things. Most people would have fallen several times by now. You picked up speed. You’re going twice as fast as you were when you started out.”

That’s not saying much.