October 5, 1999 — It’s an awkward, counterintuitive position.

Underwater. Upside-down. Sealed inside a kayak.

Down is up. Right and left are confused. Time is of the essence.

Any attempt to analyze the situation is swiftly drowned out by an intense urge to get above water — and breath again.

But breathing again is the hard part. Capsizing is easy.

“You can’t think it through,” Bruce Williams told me. “You have to feel it.”

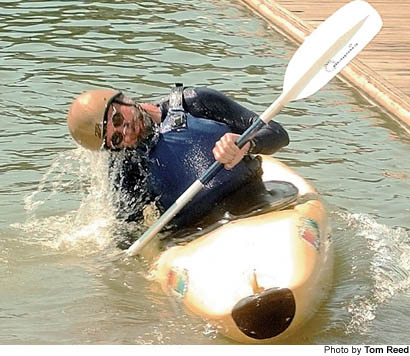

Williams, founder of the Atlanta-based White Water Learning Center of Georgia, had the unenviable task of teaching me how to roll a whitewater kayak. But, then again, that’s his job.

A certified whitewater kayak instructor since 1986, Williams fits the part. He wears shorts, sandals and a scraggly beard. He looks nothing like a man who used to work on Wall Street. But he did, until the mid-1970s, when a job with a bank brought him to Atlanta.

Here he discovered paddling. And it wasn’t long before he ditched his suit for a spray skirt and decided to ride the ups and downs of the rivers of the Southeast instead of the Dow Jones.

This past weekend he offered beginner classes on rolling at Paddlefest ’99, the Lanier Canoe and Kayak Club’s annual paddlesports extravaganza at Clark’s Bridge Park on Lake Lanier.

“I have a reputation of being patient,” said the 54-year-old Williams before we hit the water.

He has to be. The Eskimo roll, as the maneuver is commonly known, is complicated. Only a small percentage of students complete one unassisted during the first lesson.

Put simply, the roll is a technique used by paddlers to right themselves — without exiting the kayak — when they are turned bottom up in turbulent water.

Being able to stay inside the hard plastic shell of the boat in certain rough rocky rapids can be the difference between life and death.

Being able to do it during my lesson could have been the difference between a mouth full of air or one full of Lake Lanier were Williams not there to flip me before the latter ever occurred.

We began the lesson by outfitting my kayak, adjusting it to fit snuggly around my body. It is important to be able to make the boat respond to subtle movements of the hips and torso.

Then we outfitted ourselves, donning spray skirts, life jackets and helmets (with nose clips … very important!), and headed down to the water.

“Putting on the spray skirt can be the most frustrating part of kayaking for some people,” said Williams.

And fitting the neoprene skirt over the cockpit opening was indeed tricky. I have a fake Tupperware container at home that is similar. The lid shrank somehow and is now a chore to put on. I get one side clicked on, and the other pops off.

I now must contort my body over the container and hold one end down with my stomach while I fasten the other with my hands. It usually works.

You have to be smarter than a piece of plastic.

Williams first taught me the safe wet exit, which is always an option if you’re having trouble with a roll. You lean forward to protect your face — always the first step when a boat is flipped — release the spray skirt and do a somersault out of the kayak.

Then we went into the different stages of the roll, which require being taught one at a time.

“It’s a pretty complex move,” said Williams. “Most people just looking at it can’t figure it out.”

If it’s difficult to pick up visually, the roll is even harder to describe in words. But here it goes.

The basic roll has four steps: set up, sweep, hip snap and high brace. When done correctly it looks like one fluid motion.

In the set up, the now upside-down kayaker, still holding on to the paddle, reaches toward the surface and places the paddle parallel against the kayak, with both hands feeling air. A right-hand-control paddler will usually try to do this on the left side of the kayak.

The paddle is then swept perpendicular to the kayak. The left hand should be touching the boat with the paddle blade raised at a 45-degree angle above it. The right hand holds the other end of the paddle at the water’s surface. The body is arched sharply to the left, the head resting on the left shoulder near the water’s surface.

Next is the hip snap, the most important part of the maneuver. In one motion, the body coils up on the right side and propels itself to the surface. The paddler pushes up with the right leg, down with the left and throws the head to the right shoulder.

The head, still tilted toward the right shoulder, should be the last part of the body to exit the water. And, now upright, the paddler should be in the high brace position, ready to tackle the next rapid.

Should be. Instinct tells the paddling greenhorn to lead with the head and try to get a breath of air.

“That, as a result, tightens up the wrong side of the body,” said Williams.

I had the hip snap down early on, but when the paddle was added to the equation my hips no longer snapped. A common problem, I learned.

I went under dozens of times. And, dozens of times, Williams helped me back up.

I left the lake determined to try again. I told Williams to sign me up for another lesson.

Maybe leaving Wall Street wasn’t such a bad idea after all.