August 17, 1999 — “You know how to use a rotary phone?” C.W. Tate asked me as we walked through the stable. Tate pushed the front of his cowboy hat back on his head and chuckled slyly.

Things are a bit old fashioned at Mountain Creek Farms, home of C.W. Tate Cutting Horses — and Tate knows it. He wouldn’t have it any other way.

“Yeah, I think I’ll be able to figure it out,” I replied with a smile. This cowboy-for-a-day needed to make a call to the office, to the world of deadlines, computers and push-button phones.

That world seemed pleasantly out of reach from my current position: sitting in a stable on a farm in Clermont, Ga. My jeans were dusty. I had just gotten off the back of a cutting horse.

Tate’s livelihood is as old fashioned as his surroundings. Cutting has its roots in the Old West. Ranchers used horses to separate or “cut” individual cows from large herds for branding, doctoring or sorting.

A good cutting horse was an invaluable commodity, because if you didn’t brand a certain cow, your next-door neighbor surely would.

“That’s how your competition come about,” explained Tate, 56, himself a product of a ranch in Wichita Falls, Texas. “These cowboys would get together on Sunday and, hell, they didn’t have nothing to do but do the same thing they did all week. So they got to bettin’ on their horses.”

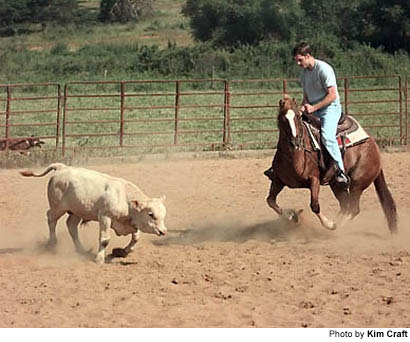

Cutting is now one of the fastest growing equine sports in the world. With a panel of judges looking on, a contestant cuts a single cow from the herd and guides it to the center of the arena. Instinct tells the cow to try and get back to the herd. Instinct should tell the well-trained cutting horse to stop the cow from doing so.

Cutting is big business these days, with millions and millions of dollars in prize money handed out each year. Tate has won his fair share of it. He had an addition built on the side of the stable to house all of his trophies.

Traveling to competitions keeps Tate busy on the weekends. Not that things aren’t busy enough for him during the week.

He trains cutting horses, 25 of them currently reside in the stables of Mountain Creek Farms. He trains riders, offering both private lessons and group classes. He’s also responsible for the care of 18 more horses out in the pasture and 100 head of cattle — not to mention anything else that needs attention on the 130-acre ranch. That makes for long 16-hour days.

“It’s a lot of work and it’s every day,” said Tate. “There’s no end to it. You get your breaks when you go to these shows. But, hell, you work twice as hard at the show. But it’s still a break from barn.”

Tate’s tanned, weathered face is softened by an easygoing smile. Everything, from his once-white cowboy hat to his fading Wrangler blue jeans to his worn leather boots, wears the dust of a hard day’s work.

He appears more comfortable on a horse than off.

I watched him as he trained a two-year-old quarter horse. He steered it into the herd of cattle, singling out a red cow on the far side of the group. They drove the cow out, and then horse and cow stood at a snout-to-snout standoff.

Tate seemed in total control.

The cow made a quick feint to the right, then the left. The horse, with a little help from Tate, mirrored its every move, keeping the cow at bay. It seemed as if this game of cat-and-mouse — or horse-and-cow, as it were — could go on forever.

“Mount up, Danny,” Tate yelled over to me. It was my turn.

“You see that yellow cow?” Tate asked me, now sitting atop Feelin’ Fancy, a 24-year-old mare. “Over there, that Charolais cow? I want you to cut it out.”

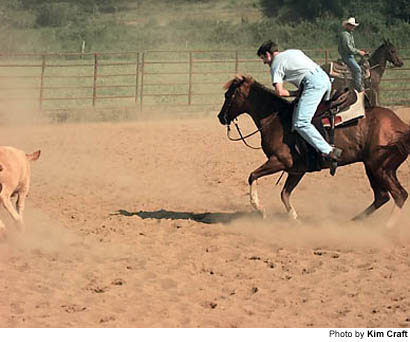

Now, the rider’s horsemanship is tested most at the beginning, during the initial cut. You need to steer your horse toward a single cow, aid the horse in chasing the cow away from the herd and then strategically place the horse in middle of the two.

So it took me a couple tries to cut out my first cow. But I eventually did. I’m not sure if it was the same cow Tate originally told me to go after. I’m not even sure if it was a Charolais. But I’m pretty sure it was a cow.

“There you go!” exclaimed my coach. “Now keep your feet out of her side. And put your hand down on her neck. Leave your reins down.”

In competition, once the cut is made, the rider is not allowed to use the reins. The horse must be given freedom to demonstrate its “cowsense.”

“Now relax on her,” continued Tate. “Just let her work that cow. You just watch that cow. That a boy. There ya go. Lookin’ good, lookin’ good!”

It’s amazing what a well-trained cutting horse can do. Sometimes it seemed to know what the cow was going to do before even the cow knew. Sometimes the moves were quick. Back and forth. Sometimes the two animals just stood there, staring at each other.

“Watch your cow, Danny. Cause she’ll trick ya. She’ll come back the other way.”

I cut a few more cows that morning. We called it quits when my horse made a sudden move and Tate said he saw “daylight” — between me and the saddle. That’s not supposed to happen. Ideally, the rider and the horse should move and think as one.

“See, you can’t think of nothing else when you’re out there,” said Tate as I dismounted my mare. “You can’t think of a late payment, a truck that broke down or a fence that needs fixin’. It’s just you, the horse and the cow.”

“So how much longer do you think you’ll be doing this,” I asked Tate as we headed back to the stable.

“I figure I’ve got about 25 more years in me,” he said straight-faced.

Shoot, maybe by then Tate will have one of those newfangled push-button phones.

Nah.