July 20, 1999 — The fly fisherman did a double take.

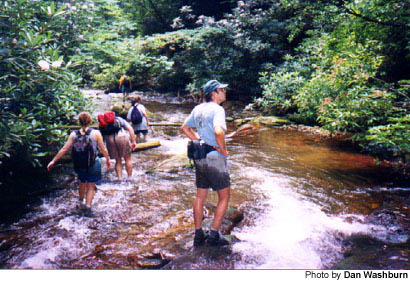

I imagine he selected this remote bend on the upper, upper Chattahoochee River expecting to encounter trout, not humans. And now eight of us were sloshing our way toward him — not one in the group carrying a rod or reel.

We crossed paths with this lone angler in the mountains of northern White County, a few miles south of Chattahoochee Gap, birthplace of the first trickles of the 436-mile river called the Chattahoochee. It was shortly after 10 a.m. and we had just set out on our day’s journey.

The angler opened his eyes wide and cocked his head to the side when we told him of our plans.

“You’re hiking all the way to the Game Checking Station?” he said, sounding half impressed, half doubtful. “Boy, you’ve got a walk ahead of you.”

We were aware of that, so we didn’t chat long. We said our good-byes and continued on.

The fisherman was the last person we saw the rest of the way.

“Not for the faint of heart!” read the description of this hike, one of the River Adventures offered by the environmental advocacy group Upper Chattahoochee Riverkeeper.

We soon realized why. Part of the Chattahoochee Wildlife Management Area in the Chattahoochee National Forest, this six-mile stretch of the ‘Hooch is wild and untamed, its banks lush with thickets of rhododendron and mountain laurel, its sky occluded by a canopy of tall hardwoods and hemlocks.

The only trail is the river itself. I was told to wear shoes I didn’t mind getting wet. Later, I wondered why I wasn’t told the same about my shorts and shirt.

“Be careful how you step and where you step,” advised our leader Joe Cook, of Rome, who warned us of the high cliff walls and waterfalls along the route. “Be real careful, because it can be real slick and you can fall a fair distance.”

He looked at his ragtag group. There were those who could possibly be of help on such a hike: Riverkeeper representatives Katherine Baer, of Gainesville, and Matt Kales, of Atlanta; Lydia Baldwin, Kales’ fiancee and a nurse; and Steve Moorman, an Atlanta nurse practitioner. Then there were three others: Ken Parkinson, a retirement planning specialist from Rome, Caroline Ball, an Atlanta teacher, and some writer from The Times who was busy trying to figure out how he was going to keep his camera and tape recorder dry.

Cook then added, “Not many people go in here.”

That wasn’t always the case. Before the Chattahoochee National Forest was officially established in 1936, many people called this portion of the headwaters home.

From Cherokee Indians to gold miners, homesteaders to lumberjacks, the Chattahoochee has seen its fair share of inhabitants. But now they are all gone.

Only the river remains.

And this portion of the Chattahoochee didn’t appear to mind its seclusion from the human race. In fact, it seemed to revel in it, providing us with myriad reminders that we were merely visitors in this primitive landscape.

Large, moss-covered fallen trees often blocked our path. The river water, at once ankle deep, would be at our waists sharply, suddenly, unannounced, slowing our already deliberate pace.

At one point we found ourselves in a long stretch of water that rose well above waist level. Single file, we waded like an army platoon sneaking up on the enemy, backpacks held above our heads like machine guns.

At least the deeper water made falling a non-issue — a pleasant change of pace from the rest of the hike, which saw us dropping like flies.

It has been said that Chattahoochee means “painted rock” and, indeed, the river’s clear waters revealed several large, bright, orange-hued stones dotting our path.

Painted rock. Beautiful to look at, slippery to tread upon. Must be a fresh coat, I thought.

One of the hikers called our adventure intoxicating … and at times I’m sure we appeared downright intoxicated. Like drunken gymnasts on a balance beam, we gingerly measured each uncertain step into the water before us, arms extended and waving to and fro in an effort to maintain our equilibrium.

Sometimes a weird contortion of the body, coupled with some rapid windmills of arms, would stop a fall. We got better at this as the day wore on. But in the early goings, it wasn’t uncommon for a hiker in front of me to suddenly disappear from sight, usually accompanied by a loud “kerplunk.”

I, too, experienced more than my share of falls. Instinctively, I would try to bounce right back up and take a quick look around to see if my spill went unnoticed. It didn’t matter. The soaked shirt was always a dead giveaway.

Sometimes we tried to avoid the hazards of the ‘Hooch and took to the land around it. When we weren’t fighting our way through rhododendron and mountain laurel, we often were avoiding — or trying to avoid — unsettled swarms of yellow jackets.

But this is the stuff of nature. For every bee there was a butterfly. For every fall in the water there was a waterfall.

And there were many moments of wonder.

“I didn’t know the Chattahoochee was that small,” said Ball. “I’ve always known it as the big river that runs through Atlanta.”

There was one point along our eight-hour hike where the Chattahoochee gushed through an opening no more than two feet wide. Two feet wide. And this tiny river becomes Lake Lanier!

This is the Chattahoochee few see. This is the Chattahoochee that Cook has grown to love.

In 1995, he and his wife Monica, both professional photographers, hiked and canoed the entire 540-mile course of the Chattahoochee, from its beginnings in the Appalachian Mountains, to the Florida state line where it becomes the Apalachicola River, to the Gulf of Mexico where it empties into the sea.

A book documenting their journey is due out next year.

“We found during our trip that, for people all the way from the headwaters to the Gulf, the river is kind of a sacred and sanctified place,” said Joe, 32. “That’s what it is for us. We grew up in the Atlanta suburbs where everything changes. Land is a place where you can put a strip mall or a subdivision. Nothing stays the same very long.

“But, for us, the Chattahoochee has never really changed. It’s always constant and always the same, regardless of what’s going on on the land around it.

“To me, it signifies home.”

And I think I know a ragtag group of seven people who now realizes why.