June 1, 1999 — Two lessons learned during my training session at the Gold Rush Boxing Club:

Always wrap your hands, and never expect to win a talking match with young Thomas Heaton.

The Gold Rush Club has the feel of a boxing gym. It is located in the heart of Gainesville, just south of Jesse Jewell Parkway, in an old feed store that occupies an odd dead-end corner where the streets of Gordon and Johnson collide.

The unassuming brick building almost looks abandoned, and five days of the week it is. But on Tuesday and Thursday evenings it is the definition of activity, a pugilistic paradise for as many as 80 youths in search of a brief escape from some of the city’s rougher neighborhoods.

“Make yourself at home,” said Danny Pridgen, the 49-year-old Gainesville barber who has governed the goings on at the Gold Rush since its beginnings in 1995. “I’ll be right with you.”

It was 6 p.m. and the Thursday-night crowd was beginning to pour in. They gravitated to different areas of the gym. The weights. The heavy bags. The speed bags. The jump ropes. The mirrors. The ring.

Some seemed on a mission. Others seemed to mill about, just happy to be off the streets and among friends.

Still less than five years old, the Gold Rush feels like an old-time boxing gym ought to. It is musty and lit sporadically. It smells like sweat, hard work.

To be heard, one must yell over the rumblings of the gym’s ambient sounds — the constant thud of leather hitting leather, the slap of jump ropes against creaky floorboards, the clang of iron weights falling atop one another, the machine-gun rat-a-tat-tat of somebody properly working the speed bag.

There is another sound at the Gold Rush — laughter. These kids are having fun.

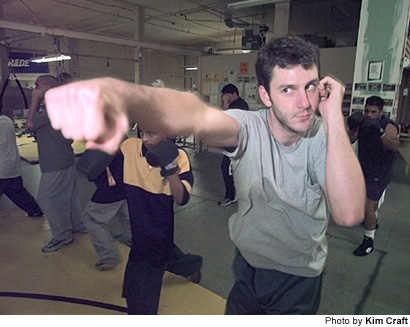

Pridgen gathered several of the crowd before a wall of mirrors for an introductory lesson on boxing’s basics. The stance. The left jab. The straight right. The left hook. The one-two combination. The one-two-three combination.

Pridgen brought out young Thomas Heaton to demonstrate some techniques. We’ll get back to him later.

We students formed an odd-looking line-up. My 6-foot-3 frame stood heads, shoulders and, in some cases, elbows above my classmates, mostly Hispanic youths — who regularly make up about 60 percent of the gym’s attendees.

Usage of the Gold Rush facility is free to all comers. Everything there is the product of donations. The building itself was provided by local philanthropist Alvin Gibson. Equipment and start-up costs were covered by a grant from the U.S. Olympic Committee in anticipation the 1996 Games in Atlanta.

Pridgen, his younger brother Johnny and the several other folks who keep the gym running are all volunteers.

After the lesson, it was time for me to start hitting things. I was put in the care of 30-year-old Junior Elizalde, who has been coming to the gym since it first opened.

As we headed over to the heavy bags, I asked Junior if I should first wrap-up my hands. He shook his head. The gym didn’t have any extra hand wraps — it is, after all, a non-profit operation, and sometimes the donation kitty runs low.

So I put gloves onto my bare hands and thought nothing of it. Elizalde put me through a half-hour workout on the heavy bags, calling out combinations for me to try. I eagerly obliged.

On top of being a deceivingly effective total-body workout, boxing is quite a stress releaser as well. Any problems you may have — an ex-girlfriend, or whatever — take them out on the heavy bag.

Elizalde cheered me on. “Remember now, turn those hips … Bend your knees a little bit, and you can really dig into it … There you go! You feel that power now, huh?”

My left hand hurt. I thought it was natural.

We headed over to the double-end speed bag, a round ball suspended between the ceiling and floor by two elastic bands. We didn’t stay long there. I had some problems hitting the ball. The heavy bags didn’t move much. This one did.

“The only way you’re going to learn to do that one is to practice, buddy,” laughed Elizalde. “It took me a while to learn it too.”

I was then passed on to the Reverend Rick Padgett, who donned the target mitts for the third phase of my workout.

First, however, I needed to inspect my hand. It was throbbing. When I took off my glove, I realized why. With the constant pounding and the friction inside the glove, I had ripped several layers of skin off two of my knuckles. They were raw and bloody.

The Reverend let me borrow his hand wraps. He’s a giving type of guy. Together he and his wife Sharron operate the Freedom and True Peace Ministry. They volunteer their time at the gym.

“It’s better to sweat in the gym than to bleed in the streets,” is their motto.

Rick works out with the kids — he had a long history in fighting sports before he got the call to preach seven years ago — and Sharron helps operate a program that provides food for the underprivileged children at the gym, which is many of them.

“The object of the mitts is not just for me to stand there and let you hit them,” explained the Reverend before our session. “The object is for me to simulate an actual opponent.”

While we circled each other, the Reverend flashed the mitts and I responded with the appropriate combinations. He gave me subtle reminders — in the form of a tap to the head or rib cage — when I began to let my guard down.

I was drenched in sweat once the Reverend was finished with me — and that is when young Thomas Heaton made his move.

He said the Times photographer at the gym told Thomas I wanted to interview him, and maybe that is true. But there was no way young Thomas Heaton was going to let the newspaper man get away without having his story heard.

For more than 20 minutes he talked to me. I barely got a word in edgewise.

I didn’t mind, either. I was tired, and I still had one more session to go with Pridgen.

It’s is a good story, too. And Heaton seemed experienced in telling it.

“I was born in Atlanta weighing 1-pound, 7-ounces at Greater Memorial Hospital and nobody game me a chance to live,” began Heaton, known as “Taz” around gym.

He grew up fighting in the streets of the Hancock Avenue Extension neighborhood on Gainesville’s southside. He didn’t think he had much of a future — until the Gold Rush Boxing Club opened.

“I got in here and I realized I wasn’t as tough as I thought I was,” said Heaton, 16, who just completed his freshman year at Johnson High. “I had to cool down and learn how to throw the basic punches.”

Now, disciplined and focused, Heaton does all of his fighting in the ring. When Gold Rush can secure the funds, he travels to boxing tournaments, and fares quite well. If someone approaches him on the street for a fight, he tells them to meet him at the Gold Rush.

“I’ve offered challenges to many people, and not many of them have showed up, but the ones who did found themselves staring at the ceiling,” boasted Heaton.

Heaton now looks toward the future. He wants to attend college on a boxing scholarship. He’s also an aspiring preacher, and will give a testimony tonight at the gym — which, I believe, should come easy for him.

“Without boxing I probably wouldn’t care about school, I probably wouldn’t care about what my mom thinks, about what my dad thinks,” said Heaton. “Boxing has brought me a long, long way physically, mentally and spiritually.”

It’s a good story. The Gold Rush Boxing Club is full of them.