May 25, 1999 — The following scene took place at convenience stores across America last week.

A family slowly approaches two men hurriedly refueling their 1987 Volvo 780. The car seems normal enough, save for the countless decals that adorn its body — cunningly disguised as a race car, someone once said.

The father, curious, begins to speak to the men. He has a series of questions.

What are you doing?

How fast do you go?

Then, after inquiring further about the car, its engine, the race, the father glances at his family, and turns back to the two men preparing to speed off, back onto the open road.

Are you guys married?, the father asks incredulously, almost in a whisper.

“That’s always their last question,” laughed Terry McLeod, of Dahlonega, whose wife Deborah, is nice enough to grant Terry one week per year to take part in the One Lap of America race, a sort of fantasy camp for serious car guys. “(Deborah) understands that it’s an illness. I’m lucky, because that’s not the attitude I hear from everybody else on the event.”

Understandably, many wives may not fully appreciate the lure of the One Lap. This year’s installment, the 16th running of the week-long race, began Sunday, May 16 and covered 4,200 miles of roads in the Central, Western and Eastern United States with stops at a different race track each day.

Nearly 250 participants driving 102 street-legal automobiles — everything from a 1998 Lamborghini Diablo to a 1994 Dodge Ram 1500 to a 1979 Buick Regal — competed in 14 high-speed, time trial and bracket drag racing events at seven of the U.S.’s top race tracks: Michigan Speedway, Heartland Park Topeka (Kan.), Pikes Peak International (Colo.), Texas World Speedway, Memphis Motorsports Park, Road Atlanta Raceway and Waterford Hills Race Course (Mich.).

On the tracks, drivers are limited only by the power of their engines and the caliber of their courage. On the roads, they are restricted to legal highway speed limits.

So erase the rash and reckless “Cannonball Run” images from your mind. Only the results from the tracks count in the race’s standings.

“Police are notified along the route in advance,” said McLeod, 52, chief information officer at North Georgia College when he’s not traversing the country in the ’87 Volvo, which falls into the race’s Vintage Foreign classification. “If you get a ticket, you’ve lost $100 or so and you’ve spent 20 minutes on the side of the road. It’s kind of stupid to do the extreme kinds of things.”

And 20 minutes spent on the side of the road are 20 minutes you could be sleeping in a bed somewhere — an extravagance not often enjoyed by One Lap participants.

“If you see that you’ve got two or three spare hours, you may dive into a motel and get a shower and a couple hours sleep and then you’re at the next track and you do it again,” explained McLeod. “The poor guys in the back of the pack tend to sleep most of the time in their cars.”

I caught up with McLeod and his teammate for the past four One Laps, Geoff Thornton of Lyme, N.H., at Road Atlanta. It was Friday, and they had already been on the road for six long days.

“I actually slept in my own bed,” smiled McLeod, whose Dahlonega residence is less than an hour away from Chestnut Mountain, home of Road Atlanta. “Had a nice leisurely shower this morning. Ate breakfast sitting at a table. It’s a luxury not many of these guys get on the trip.”

But McLeod and Thornton were tired. Very tired. They had already traveled 3,292 miles, some tougher than others.

Take night number one, for example. On the trip from Brooklyn, Mich. to Topeka, Kan. the state of Iowa presented the drivers with a slight problem — tornadoes.

“We could see transformers popping when the tornado came across in front of us,” recalled McLeod. “Plus the rain was going up, not down. That was a good sign that we were in for something severe.”

The duo made it through, however. They also made it through the 862 mile stretch, the event’s longest, between Pikes Peak and Texas. By the time they hit Road Atlanta, they were running in the top 20, and their road-weary bodies had managed to find a bed nearly every night. Things were going well.

Not so for all the race’s entrants. Going into Friday’s events a dozen cars had already been forced to drop out.

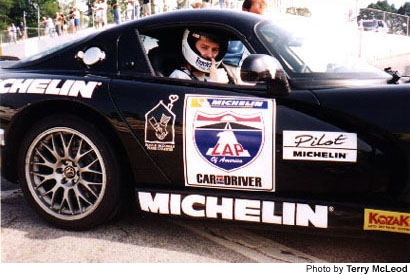

On Friday, the primary concern for Thornton, who does all of the team’s driving on the tracks, was to make sure the Volvo — which, by the way, has a 380-horsepower Corvette engine hidden under its family sedan exterior — didn’t join the ranks of the eliminated with just one more day to go. And that wouldn’t be difficult at Road Atlanta, the most challenging track on the One Lap circuit.

“I try to go slow,” said Thornton, 44, an architect, who got the Volvo up to about 130 mph that day (every race fan with a funny bone must see a boxy Volvo speed around a track at least once!). “It’s hard sometimes. You get the fever. But I’ve got three kids, a wife, a business. This is just entertainment.”

I caught the fever Friday — a mild case — in a Dodge Viper. The car slid around Road Atlanta’s twelve tricky turns and hit 140 mph on a straightaway. It was better than any roller coaster ride. My stomach is still working its way back down from my throat.

But I was well rested. And I was not driving. It was a mild case, indeed.

For McLeod and Thornton, however, the illness is severe. The $2,000 dollar entry fee, the more than $1,000 spent along the way, the tremendous exhaustion, it’s all worth it. These are serious car guys.

“We get to do something that a lot of people don’t ever get to do, and that’s to run on some of the greatest race tracks in the United States,” said McLeod. “It’s such a unique thing for us. It usually takes me about a week to recover from the fatigue factor. But it’s always a good time. And there’s nothing like it, nothing else like it in the world.”