February 16, 1999 — As Carl Kirkpatrick’s truck negotiated the roller-coaster drive to the top of Toccoa’s Currahee Mountain, I observed a dozen or so vultures hovering above the summit that lay ahead.

“The buzzards circle the mountain looking for dead climbers,” said a straight-faced Carl, as he drove me closer to my first date with the sport of rock climbing.

I swallowed hard and kept my eyes on the birds. They continued to brood over the bluff, which evidently was all out of dead climbers.

They must have known I was coming.

“I’m just kidding,” chuckled Carl, 39, of Gainesville, a climbing instructor at Appalachian Outfitters in Dahlonega. “This is going to be great fun.”

Still, there is no laughing off the dangers inherent to rock climbing.

This is a sport that has obituary sections in its magazines.

This is a sport that separates its participants not into bad or good, rather dead or alive.

But, this is a sport that is addictively intoxicating in spite of — or perhaps because of — its inherent dangers.

“There’s something about this sport that just clicks in some people,” said Michael Crowder, 35, also of Gainesville, who was waiting for us at the top of Currahee. “If it clicks in you, you might as well give up, because you’re going to do it until you die — or until it kills you.”

Rock climbing clicked early in Michael, a self-professed “adrenaline junkie” who has been climbing for nearly 20 years. He heads west regularly to tackle the large walls of the Rockies.

His mane of black hair pulled back into a pony tail, Michael exudes the semi-sane personality one would expect from a lifelong climber. His hobbies include “anything that involves speed and gravity.”

Michael has tried a lot things in his 35 years, but he keeps coming back to rock climbing.

“Rock climbing is the only thing that still kicks my hind end every time I go out,” said Michael. “Every day it’s got something to throw in my face. It’s a sport that’s unmasterful, and about the time you think you have it mastered, you usually crater and die.”

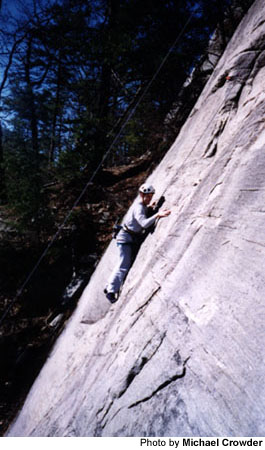

I never felt unsafe while scaling Currahee’s 100-foot granite “slab wall” — Carl and Michael, with nearly 40 years of climbing experience between them, made sure of that. But there were many times when I was scared, a common sensation among climbers, and part of the sport’s draw.

“I don’t want to say I climb to get scared,” said Carl, a free-spirit who has been climbing since the late 1970s. “But I like that feeling right after the scared leaves you. That’s the part that’s good.”

“I don’t want to say I climb to get scared,” said Carl, a free-spirit who has been climbing since the late 1970s. “But I like that feeling right after the scared leaves you. That’s the part that’s good.”

The scared didn’t completely leave me until I was back in Carl’s truck, heading home. But many of my fears died when I first learned to trust the climbing equipment specifically designed to keep me alive.

I was top-roping — probably the safest method of climbing around — where the 200-foot nylon rope is strung through an anchor at the top of the cliff, with one end tied to the climber’s harness, and the other attached to the belayer, the person at the base of the cliff applying tension to the rope.

I had climbed up about 15 feet, when Carl, my belayer, told me to fall.

“Just lean back and let go of the rock,” he said. “You’ll be alright.”

I made sure my helmet was securely fastened and did it — and I barely moved. I hung there, about 15 feet above the ground, and realized everything was going to be OK.

The bond between climber and belayer is a strong one. It has to be.

“Right now is where the complete trust comes into play,” said Michael, smiling up at me. “If he was a sick and sadistic kind of guy, he could just let go of the rope and let you bounce right now. When you think of it in that context it’s kind of a weird feeling.”

I was strangely comfortable with my life in Carl’s hands. And I was ready to tackle the granite mass before me, one step at a time.

“On belay?” I asked Carl.

“Belay is on,” he responded.

“Climbing.”

“Climb on.”

I took to the wall, examining it for each and every ledge, depression, or crack, anything that would support one or two of my fingers. In chess-like fashion, I tried to strategize my moves, remembering that every hand hold becomes a foot hold.

Foot holds are important. It is a lot easier to stand on the wall, than to hang from it. Good climbers always have their feet on the rock. Good climbing shoes — tight, with a sticky rubber sole — allow that to happen more easily.

With coaching and encouragement from Carl and Michael down below, I found a rhythm. A very slow rhythm. But a rhythm nonetheless.

And if a particularly challenging move put a halt to my rhythm, I would pause, reach into the pouch on my harness and chalk up my hands, acting as if I was in total control.

But some things were far beyond my control, like the constant shaking in my left leg.

“That’s a common phenomenon,” laughed a knowing Carl.

“We call that sewing machine leg,” added Michael. “Sometimes you call it the fear of death. That’s when both your legs are shaking and you’re crying.”

I eventually reached the top, exhilarated and exhausted, and with one of the truest feelings of accomplishment of my life.

I sat atop that 100-foot cliff and took in its majestic view. For that one moment, I felt invincible.

I looked up to the sky and thumbed my nose at the buzzards still circling above.

Then I paused, and looked to the ground 100 feet beneath me.

I still had to make it back down.