| Growth

marks rise of grass-roots league Hispanic-borne soccer association realizes dream with title bout in City Park |

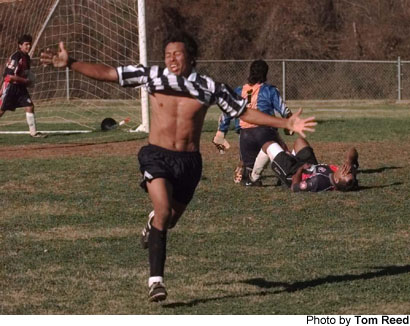

By Dan Washburn The Times December 5, 1999 — It's a Sunday ritual for thousands of Hall Countians — and it has nothing to do with church. One ball. Two goals. And several generations of tradition. This is the Gainesville Georgia Soccer Association, a tangible barometer of Hall County's ever-changing ethnic makeup. With 46 teams and almost 1,000 participants — the overwhelming majority of whom are Hispanic — the association is one of largest adult athletic leagues in the county. It is also one of the most unnoticed. Outside of Northeast Georgia's tightly knit Hispanic community, very few people have recognized the unprecedented growth and popularity the adult soccer league has experienced during its somewhat disjointed 12-year existence. On Dec. 12, however, the league will be hard to ignore. More than 3,000 screaming fans are expected to pack into City Park Stadium for the league's fall season championship match, its first-ever in a real stadium. The match will be the league's crowning achievement to date, and a sign that the Gainesville Georgia Soccer Association is here to stay. "We're talking 10 years, man," an excited league president Mario Mendez exclaimed upon hearing that Gainesville Parks and Recreation had accepted his City Park proposal. "Ten years and we have never played our final in a stadium. This is huge for us. This is a dream come true."

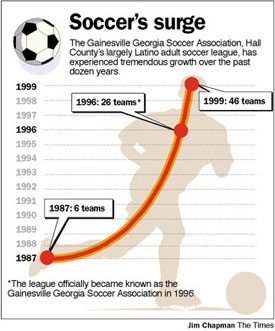

"It was just dirt," laughed the 36-year-old Mendez, shaking his head. "It was pitiful." Dirt fields were the least of the league's problems early on. Disorder was the norm for several years after the league began with just six teams in 1987 as an offshoot of another Latino league that played from the early to mid-1980s. "In the past we could not take our families to the games," said Fernando Sanchez, 29, who has been playing in the league since the early 1990s. "There was no organization. And there was a lot of fighting and bad language and things like that." Haydee Anderson, publisher of the Gainesville Spanish-language newspaper Mexico Lindo, noticed those concerns and began efforts to help the league secure playing fields — still a hot-button topic for today — in 1990. "Americans have rules of order," said Anderson, a native of Peru who moved to Gainesville in 1976. "Hispanics, well, work differently. One of the things that they wanted to have was a democratic group. And that's one of the things that we implemented." That happened in 1996 when Anderson and others established a constitution and a strict set of rules and regulations. The Gainesville Georgia Soccer Association was officially formed. Mendez took over as the organization's president in 1997. Under his watch, the league has grown from 26 teams to 46 and is hot on the heels of softball, still the dominant adult sport in the area with 148 teams this year, according to Gainesville Parks and Recreation. Rooted in cultureAnd no longer are players reluctant to bring their wives and children to games. Now every Sunday, game day, a true family atmosphere prevails. Women socialize in the shade. Children run about, kicking soccer balls back and forth. Vendors serve up traditional Mexican fare. And the many die-hards stand with eyes fixed upon the action on the playing field, often voicing their approval or disapproval — loudly.

There are two seasons which run from March to July and August to December. During each season, the top three teams from the second division swap places with the bottom three teams from the first division, giving every match added importance. Not that the players need any extra incentive to take soccer seriously. Most of them come from Central and South America, where soccer is the national pastime. "Soccer is a passionate game for them," said Mendez, from Belize, who plays for the Honduras team in addition to his presidential duties. "It's like a religion for most players. They talk about the league all week long. The poultry plants (where many of the players work), that's where the rivalry starts." And the rivalry carries over onto the field, where the quality of play, especially in the first division, is exceptional. "When you get into playoff time, it gets really intense," said 35-year-old Brad Puryear, one of the few Anglos in the league and a former member of the soccer team at Marshall University in West Virginia. "There are some big rivalries out there. And although it's intense, it's clean play. Just hard, aggressive play." That such a large, and serious, soccer league has sprouted so quickly — right in the heart of American football country — likely befuddles many longtime Northeast Georgians. But the region is changing, dramatically. Just look at the statistics. In 1990, the Census Bureau counted 4,558 Hispanics in Hall County. In 1998, the bureau increased the count 118 percent to an estimated 9,938 Hispanic residents. A report by the Center for Applied Research in Anthropology at Georgia State University in Atlanta, however, says more than 53,000 Hispanics live in Hall. The true figure is likely somewhere in between the two extremes. But the growth is unmistakable. The reasons for this migration are simple. There are jobs in Hall County, lots of them. And they pay much better than those available in Central or South America. Often workers can earn more money in a half-hour in one of Hall's poultry plants or another blue-collar job than they can in an entire day back home. It's only natural that these immigrants bring with them the traditions and customs of their respective homelands. And no sport is more ingrained into the Hispanic culture than soccer. "Soccer is like a tradition," explained Durango team member Eric Sanchez, 29, who grew up in Mexico City. "It is the main sport in Mexico. You can see it in the streets, you can see it in the playgrounds. We use any kind of structure just to play soccer. We like to play everyday, we play all year long. It can be cold, it can be hot. It doesn't matter for us." As long as the influx of Hispanics into Hall County continues at its current rapid pace, Mendez said the soccer league, likewise, will grow as rapidly. "If we started three years ago with 20 teams," he said, "and now we have almost 50, just imagine the next three years." Fields in demandOne major hurdle stands in the way of this future growth — field space. There just simply aren't enough fields to accommodate Hall's soccer-playing population. "Right now the biggest problem is finding a place to play," said Socorro Aguilar, 42, who coaches the River Plate team in the league's second division. "Every day the league is growing and there aren't even enough places to play now." Currently, the league plays games nearby at Gainesville College and Murrayville Park. Due to a lack of field space and the number of teams, games must also be held in Dahlonega, Buford and Jefferson. "Players get frustrated because most people here, they don't have cars," said Mendez. "So they always have to hitch a ride. They want to play so they go wherever we send them, but we need more fields. There's no other way."

Gainesville Parks and Recreation director Melvin Cooper admits that even with the nine new fields, "It's going to be a tight fit." In addition to the Gainesville adult league, Hall County is home to the Lanier Soccer Association youth leagues, which have more than 2,000 participants. "I think our first obligation is going to be to the youth leagues of our community," said Cooper. "But I think that there's going to be adequate space and adequate field time for adults to be worked into the mix." Anderson desperately hopes that is the case. "The children are first, and I understand that," Anderson said. "But we should not also forget the adults. Because you keep them off the streets, off the drugs, off the drinking." Sponsors ease costThe adult league uses some of its fields free of charge. Others it must pay for. Each year Mendez draws up a budget of league-related expenses, and the teams share in the costs evenly. Nothing more, nothing less. This season, that figure came out to about $20 per player. Players are also responsible for paying referees and buying their own equipment and uniforms — which can often be quite expensive. League uniforms often mimic those of popular Latin American professional soccer teams. "They prefer to have expensive uniforms rather than having insurance," chuckled Mendez, who said players easily spend more than $50 on their jerseys and shorts. Roughly half of the league's teams have sponsors. Hayes-Lammerz International, an aluminum wheel manufacturer with a factory in Gainesville, for example, purchased uniforms for Durango, which has several Hayes employees on its roster. "We have a basketball team as well as a softball team," said Lisa Milroy, human resources manager for Hayes, which has a number of Hispanic employees. "So we thought this would be a good addition to the extracurricular activities that we sponsor. And they take a lot of pride in it. They are good. They are very good." Fernando Sanchez, a shift supervisor at Hayes, said the gesture is appreciated and boosts employee morale. "(Lisa) helps us a lot," Sanchez said. "Everybody is happy over here working with Hayes because we get a lot of support from them." Alfredo Figueroa, manager of El Maguey restaurant on Brown's Bridge Road in Gainesville, said he hopes to set a precedent by sponsoring the second division Maguey team. "If I sponsor a team, I hope that somebody else will sponsor another one, too," said Figueroa, 39. "Right now soccer is getting bigger here in the United States and I hope more people from businesses can get interested and sponsor more teams. When told of the thousands of soccer fans expected at City Park for next Sunday's championship game, Figueroa displayed not a hint of wonderment. "For Hispanic familes (watching soccer) is one of the more attractive things that they do on the weekend," he said. "Sometimes they would rather go see a soccer game than eat. That's how important it is." See also: Dan Washburn is a sports writer for The Times in Gainesville,

Ga. |

City

Park Stadium must seem like Turner Field for Mendez, who remembers one

season several years ago when the league held its championship on a

rocky pitch of land adjacent to the Winn Dixie supermarket on Limestone

Parkway.

City

Park Stadium must seem like Turner Field for Mendez, who remembers one

season several years ago when the league held its championship on a

rocky pitch of land adjacent to the Winn Dixie supermarket on Limestone

Parkway.

The

league's teams are separated into two divisions. Upper-echelon teams

occupy the 14 coveted spots in the highly competitive first division.

The second division is split into two 16-team groups.

The

league's teams are separated into two divisions. Upper-echelon teams

occupy the 14 coveted spots in the highly competitive first division.

The second division is split into two 16-team groups.

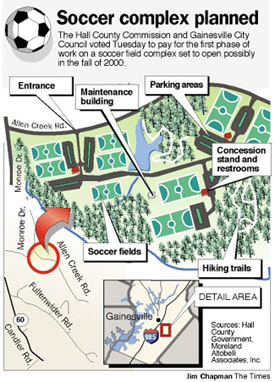

Construction

on the new Allen Creek Soccer Complex southeast of Gainesville, a $3.2

million venture funded jointly by Gainesville Parks and Recreation and

Hall County Parks and Leisure Services, is under way. The complex is

expected to be completed in late 2000 or early 2001, and will include

nine lighted playing fields, one with a 5,000-seat stadium.

Construction

on the new Allen Creek Soccer Complex southeast of Gainesville, a $3.2

million venture funded jointly by Gainesville Parks and Recreation and

Hall County Parks and Leisure Services, is under way. The complex is

expected to be completed in late 2000 or early 2001, and will include

nine lighted playing fields, one with a 5,000-seat stadium.