June 27, 2002

Soccer Watching: Late-night confessions of a World Cup junkie

In a current television commercial, the main character ends up flat on his back in the middle of a crowded sidewalk. He is motionless.

Another man takes the guy's arm and sees that he's wearing a bracelet, kind of like a medical I.D. tag. He flips it over and finds the image of a soccer ball.

"It's all right," the man announces to the growing crowd. "He just needs some football."

Lately, I can relate. I've been leading a double-life: journalist by day, junkie by night. I've been a World Cup fan in America.

It's been a lonely, nocturnal existence. Japan and South Korea are the tournament hosts this year. And while you are reading this story today, it is probably already tomorrow in Tokyo.

Game times in Georgia have been 2:30 a.m., 5 a.m. and 7:30 a.m. Not exactly prime time.

But I've tried to stay up, or wake up, for many of them. During daylight hours, I walk around like a zombie, my eyes glazed over like soccer balls.

I know there are others out there like me. Friends of mine in New York, and even Atlanta, tell me about late-night and early-morning trips to bars for World Cup watching. Throngs of fans have gathered to watch matches at Major League Soccer stadiums throughout the country. And despite their early-morning starts, the games are drawing a record amount of viewers on television.

But in Gainesville, I often feel like I'm going at this all alone. Bars close before game time. And if they didn't, I doubt crowds would gather for the games, anyway. Gainesville is the Poultry Capital of the World. I'm not sure where the soccer capital is, but I have a feeling it's a long way from here.

Tuesday in South Korea, millions and millions of soccer fans took to the streets to watch their countrymen play. I watch matches in my living room, joined only by a bottle of beer and a box of Golden Grahams. At halftime, I step onto my porch -- and get serenaded by a chorus of crickets.

I thought about turning my house into an after-hours speak-easy for local soccer fans. But I couldn't figure out how to advertise it without getting arrested. Maybe I'll start a self-help group to help those afflicted deal with their World Cup addictions.

There are sure to be some withdrawal symptoms after Sunday morning's championship match between Brazil and Germany.

It's nice to know, though, that there are others who have it worse than me. Franklin McIntosh, director of the Lanier Soccer Association, has not missed a match. That means since May 31, he's seen 62.

"To me, it's something very special," said McIntosh, 38, a former professional soccer player originally from football-friendly West Bromwich, England. "But I'm extremely tired right now. It only happens once every four years, so I like to experience it live."

Often, McIntosh would watch the matches straight through the morning -- from 2:30 a.m. to 9:30 a.m. -- and then head off to work, not to return home again until after 10 p.m. Then it's a quick nap before another night tuned in to ESPN.

"It just depends on how good the middle (5 a.m.) game is," explained McIntosh. "If the middle game is a real good game, I will watch it. If it's not, I will tape it and watch it later on in the evening. I'll watch the 2:30 game, go take a quick nap, and get up for the 7:30 game."

For most matches, McIntosh, like me, watched alone at home. But when England played, he headed down to the Rose & Crown pub in Buckhead.

"They stayed open extra late," McIntosh said. "The atmosphere was just unreal. But it only happened for England."

I have a confession to make. I've been a bad, bad American. Last Friday, I stayed up to watch the quarterfinal match between England and Brazil. After England was eliminated, I went to bed at 4:30 a.m. ... and set my alarm to sound 2Ç hours later.

I needed to be up in time for the U.S.-Germany match at 7:30 a.m. This was a history-making match and there was no way I was going to miss it. The Americans hadn't been in the final eight since 1930. They have never made it to a final four.

Now, one of the perks of my profession is that I rarely have to wake up to an alarm. A sports writer's workday starts late, and ends much later. So sleeping in is not a problem.

Perhaps, then, my lack of practice in clock-programming explains why on Friday I set my alarm for 7 p.m. instead of 7 a.m. Perhaps it explains why I slept through the entire dadgum match.

The U.S. lost 1-0, but that didn't ease my pain. Now I must wait -- at least four more years -- to watch the Americans play in the World Cup again.

Maybe in 2006 I won't feel like such a loner. Maybe this year's U.S. run has brought some more fans into the World Cup fold.

Last Friday, after I finally woke up, I was pleased to find soccer a topic of discussion on the basketball courts at the Family Life Center. That hadn't happened before. It hasn't happened since, either. And likely won't for at least four more years.

But I'm still talking about the World Cup. I was talking about it Tuesday morning after I watched Germany defeat South Korea. I was talking about it Wednesday morning after I watched Brazil take down Turkey.

And now, I know at least one other person whom I can talk about it with. But even McIntosh is growing weary late in this late-night World Cup.

"I still had a good time watching the matches, but it just seemed more of a job to get up and watch the games," McIntosh said. "I am so tired right now, it's unbelievable. I don't want the Cup to end, but at the same time, I'm ready for it to end."

Just two more matches to go, Franklin.

I'll be up for both of them. Right now, though, I need a nap.

June 20, 2002

Mississippi Handgrabbing (Part Two): Finger food

Hands are bait when grabbing giant catfish

Forget about forethought -- or any other type of thought, really -- when you stick your hand in front of a 40-pound catfish, hoping that the monster mistakes your fingers for food. Thinking can only cause problems. It's best to do such things with your brain on blank.

Forget about forethought -- or any other type of thought, really -- when you stick your hand in front of a 40-pound catfish, hoping that the monster mistakes your fingers for food. Thinking can only cause problems. It's best to do such things with your brain on blank.

So, when I first reached my hand into a wooden box occupied by a big, bad blue catfish, the only thing weighing on my mind was the muddy water of the Big Black River -- and the words of Mississippi handgrabber Ricky Liles.

"You've got to get your hand in the fish's mouth," he said. "Because that's the onlyest way you're going to catch him."

The folks I met the following day along the banks of the Ross Barnett Reservoir spillway outside of Jackson, Miss., would beg to differ. They were fishing for catfish the regular way, with rods and reels.

I told them about handgrabbing, and that I had tried it. When they were done eyeing me as if I was an escapee from the Mississippi State Insane Asylum, they offered their opinions:

• "Man, I'm not sticking my hand up in nothing in no water," Cortez Green, 33, said. "I don't care if there's tons of fish in there."

• "That's why they made these," said Kevin Primus, 35, pointing to his pole.

• "I know the Big Black. Alligators. Snakes," said Ruth Usry, 56, shaking her head. "There's alligators all in the Big Black. And water moccasins."

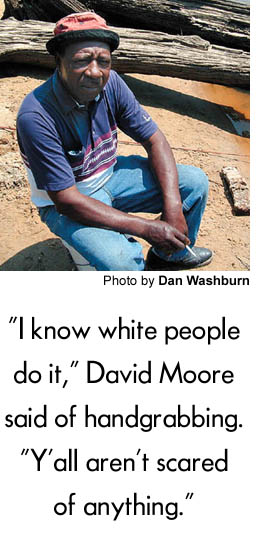

• "I know white people do it," David Moore, 63, said. "Y'all aren't scared of anything."

• "I know white people do it," David Moore, 63, said. "Y'all aren't scared of anything."

Handgrabbing is not for everybody. It's an activity practiced by men many believe to be either half drunk or half crazy. But it's also an activity that has been around for hundreds of years.

In 1775, trader-historian James Adair first documented "a surprising method of fishing under the edges of rocks" performed by American Indians in the South. Today, the idea is still the same. Handgrabbers have just perfected the process a bit.

Wooden boxes, dozens of them, lie on the bottoms of the Big Black River and Ross Barnett Reservoir. A large number of these custom-made catfish cabins come courtesy of Liles, Keith Lane, Gerald Moore and Mike Willoughby -- the guys from mississippihandgrabbing.com.

The boxes, often made of durable cypress wood, are the size of coffins. They are placed flat on the river and reservoir floors. An opening, big enough for a giant catfish to fit through, is cut into the end of the box that faces downstream.

During spawning season, male and female catfish seek the shelter of the boxes -- in pairs, of course. Once the female lays the eggs, the male chases her off and guards the eggs viciously until his fingerlings are hatched ... or until some redneck reaches in the box and puts a halt to the whole process.

Many states, in fact, have banned handgrabbing, saying it's not a sporting way to catch fish.

"I think the ones who say that," said Liles, 43, of Canton, Miss., "is the ones, really honestly, who don't have the nerve to do it."

Liles and his crew contend that they raise far more catfish than they catch, saying that they purposefully leave several of their boxes untouched each season.

I asked Ron Garavelli, Mississippi's chief of fisheries, for his thoughts on the matter. He's been on the job for 27 years, and handgrabbing has been legal for all of them.

"Let's just say I don't think the catfish population is hurting because of handgrabbing," said Garavelli, whose response to my next question -- Are you a handgrabber? -- came rather quickly. "No," he said. "I'm not the type of person that puts my hands in places that I can't see."

Not many people are. If any species is at risk of endangerment, Garavelli said, it is the handgrabber.

"It's a dying art," Garavelli said. "I don't think there will be a whole bunch left after this generation. You don't see many young handgrabbers out there."

When 56-year-old Gerald Moore was a "young 'un" in Smith County, Miss., he handgrabbed on the Leaf River.

"Back then, we didn't know about no damn box," Moore said. "We'd find an old cypress log underwater. We done it for the food."

And still today, Moore and his cadre of catfish wranglers do it as much for the food as for the fun. But, Moore will tell you emphatically, they "ain't after the damn blue cat."

And still today, Moore and his cadre of catfish wranglers do it as much for the food as for the fun. But, Moore will tell you emphatically, they "ain't after the damn blue cat."

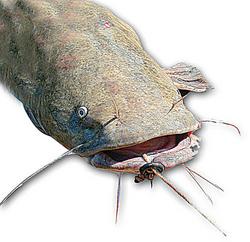

"We're after the flathead," said Moore, who estimates that each season his group catches more than 3,000 pounds of flatheads, yielding more than 1,000 pounds of meat. "Because, as far as we're concerned, the flathead is the best fish you can put in a frying pan. We don't even keep the blues."

Blue cats are harder to skin, and often even harder to swallow. Unlike the flathead, which prefers its meals to be on the move, blue cats often dine on the dead ... or anything else that floats in front of its mouth.

"Your blue cat has got probably twice stronger jaws than a flathead, kindly like an alligator," Liles said. "When they bite down on something, they can hold that grip."

So, when you are submerged in several feet of water and a blue cat swallows your entire hand, you don't have long to meditate on your next move. You'd be surprised how expendable extremities become when your only other option is drowning.

In one such situation, Liles -- who, by the way, can't even swim -- remembers sitting at the bottom of the river, running out of air. His right arm was stuck halfway inside a blue cat in a box.

In desperation, Liles placed his feet on either side of the box's opening, and with one powerful push, forced his hand out of the fish's mouth -- through the vise-like jaw and thousands of tiny teeth. Imagine running your knuckles against a cheese grater.

"You're going to lose some skin," Liles said. "But, hey, you've got to breathe."

In an early-morning haze three Saturdays ago, we traveled a lonely dirt road through cotton fields and backwoods to a steep and muddy put-in on the banks of the Big Black. We got in our johnboats and journeyed 10 miles upstream. Recent rains made the river rise. A white froth had settled on the surface, making the Big Black look like a giant root beer float.

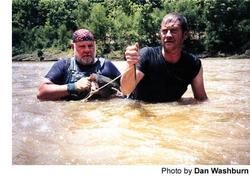

Using Lane's mental map as our guide, we made our way back downstream and checked the sunken boxes in our path. The 55-year-old Lane -- handgrabbing for 30 years -- would wade, sometimes neck deep, through the swift water, holding a silver pole like a scepter. When he'd arrive at a box, he'd stick his feet and the pole into the opening.

Using Lane's mental map as our guide, we made our way back downstream and checked the sunken boxes in our path. The 55-year-old Lane -- handgrabbing for 30 years -- would wade, sometimes neck deep, through the swift water, holding a silver pole like a scepter. When he'd arrive at a box, he'd stick his feet and the pole into the opening.

Sometimes the boxes were clean and empty, a sign that the catfish, in Moore's words, had already "done spawned and gone."

If a box is occupied, it's often easy to tell. The catfish go crazy. They make their surroundings shake like a subway car.

"You can hear it underwater," Liles said. "It sounds like thunder."

At that point, the checker becomes the blocker and seals the opening with his feet until the grabber can get his gloves on.

Grabbing can be grueling. It is an often time-consuming task performed primarily underwater. And my companions were already short of breath from smoking cigarettes.

The grabber wedges his arm past the blocker's legs and into the opening. (It's best to stick your arm in up to the shoulder, so the fish trapped inside have no room to make a run for it.) Then, it's a matter of poking around until you find something that feels like a fish head. Often, the fish head finds you.

Ideally, the fish bites down on your fingers and leaves your thumb alone. That way, you can grab on tightly to the cat's lower lip. That's when you've got him. Although, to be honest, it often felt like the fish had me.

It's an odd feeling when a known predator puts its mouth on you. It's a sensation that's hard to put into sentences.

"Well, it's ... it's, uh ... well, I really don't know how to describe it," said Lane, of Waynesboro, Miss. "It's just something biting you."

If it's a small fish -- and in the world of handgrabbing, that means about 30 pounds or less -- the grabber will pull it out of the box and come to the surface with the fish in a headlock.

For the big ones, the ones that would likely fight their way out of a simple wrestling hold, grabbers carry a brass spike attached to a long piece of rope. The spike goes through the fish's lower lip and out its mouth. With the rope looped around the lip and wrapped around the grabber's hand, escape is almost impossible.

"This is the golden rule," warned nationally known outdoorsman and novice handgrabber Preston Pittman, who came along on our adventure to film footage for a new outdoors television show. "It's a long walk home, if you let one get away."

"This is the golden rule," warned nationally known outdoorsman and novice handgrabber Preston Pittman, who came along on our adventure to film footage for a new outdoors television show. "It's a long walk home, if you let one get away."

The first nine boxes we checked that morning furnished us with four flatheads, including the 53-pounder Willoughby pulled out on our first stop of the day. Box No. 10, I would soon find out, had my name on it.

"Just stick your arm in there and see if you can feel him," Lane said.

I took the plunge, but the cupboard was bare. Mr. Catfish was holed up in the far end of the box. That's when Lane's pole came into play. A couple pokes, and the catfish had changed its position.

"He's up there now, over my foot," Lane shouted. "He's over my right foot right now."

I went under again and felt the fish's head right away. It was kind of like coming across a ripe melon at the grocery store. At that moment, I was thankful that the water was so muddy. I had no desire to stare into the mouth of whatever was now attached to my arm.

I was in relatively shallow water, so I could bring my head up for air. "I've got it," I gasped.

Liles stuck his hand down to feel the fish. He paused, and then announced to the group gravely, "It's a blue."

Willoughby looked concerned, which didn't help me much: This blue was biting my hand.

"Don't have him string it if it's a blue," Willoughby said. "Just let him come out with it."

I went under again, prepared to do my best Sergeant Slaughter impression and put the damn blue cat in a "death grip" like Moore told me to.

"Are you sure it's a blue?" Lane asked Liles. There was so much worry in his voice, I likely would have polluted the river had I not been underwater when he said it.

"Are you sure it's a blue?" Lane asked Liles. There was so much worry in his voice, I likely would have polluted the river had I not been underwater when he said it.

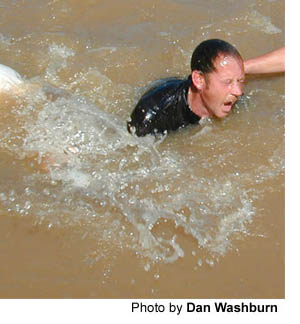

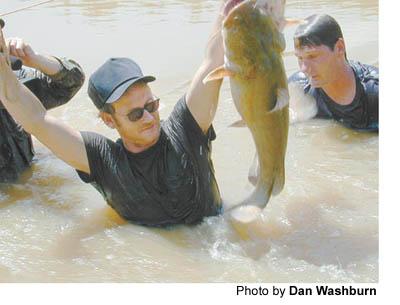

After a short underwater struggle, I shot out of the Big Black with a big blue in tow, my left arm wrapped tight around its repugnant mug.

Soon, I was laughing. And so was everyone else. I was accepted. I was part of the group. My rite of passage weighed 25 pounds and was still trying to eat my right hand.

"My man!" Willoughby exclaimed. "Got him a blue!"

Later on, another box had my name on it. It housed two flatheads, a male and a female who weren't happy that I interrupted their party. The second, and larger one, bit me hard. I uttered some words that Pittman will have to edit out of his TV show.

Near the end of the afternoon, a man yelled to us from the only other boat we passed that day.

"How did y'all do?" he asked.

Moore remained poker-faced. We sat on coolers that contained 14 fish, a catch that weighed close to 350 pounds.

"Just some small ones," Moore said. "Nothing big."

As we drove off, Moore turned to me and cracked a sly smile. With the slime of a 30-pound flathead still glistening on my T-shirt, I smiled back.

I was finally in on the joke.

Part One: Man vs. Fish

June 13, 2002

Mississippi Handgrabbing (Part One): Man vs. fish

Mississippi 'masters' lure lunkers ... using only their hands as bait

Mike Willoughby emerged from the mud-brown Mississippi water as if he were part of a river baptism, as if the very spirit of the Holy Ghost had taken possession of his being.

Mike Willoughby emerged from the mud-brown Mississippi water as if he were part of a river baptism, as if the very spirit of the Holy Ghost had taken possession of his being.

But Willoughby didn't come up from the Big Black River singing. He didn't say, "Hallelujah."

Instead, Willoughby grimaced and grunted. He appeared to be in pain.

"He come up and bit me and twisted off," the 33-year-old paint contractor from Jackson, Miss., said before groaning again. "Felt like a good fish."

Then, Willoughby took a deep breath and disappeared into the water again. He was trying to coax a giant flathead catfish into biting his hand.

After his third dunk into the drink, Willoughby spit water, gasped for air and warned us again that the fish was "a good 'un."

"Alright, I'm fixin' to come out with him," Willoughby announced before going under a final time.

I suppose I shouldn't have reacted with so much shock when Willoughby struggled to the surface with a 53-pound creature in his arms. I mean, I had seen photos and read accounts of men fishing for colossal catfish using only their bare hands. But I always remained skeptical.

Even after Willoughby lugged his leviathan to the boat and placed its still spasmodic body into a cooler, part of me -- the logical and rational part -- questioned the validity of the whole venture. To the uninitiated onlooker, what goes on under the cover of muddy water is a mystery.

Perhaps it was a trick, I thought. Willoughby was the magician and the Big Black River was his big black hat.

Perhaps it was a trick, I thought. Willoughby was the magician and the Big Black River was his big black hat.

But the monstrosity Willoughby removed from the river was far from cute and cuddly. It was slimy and prehistoric and ugly as sin. It looked like Edward G. Robinson ... hit in the face with a shovel.

I stared, and the fish stared right back. Its wicked-looking whiskers wiggled with each dying breath.

This was most definitely real. And, I realized with mounting misgivings, I soon would be asked to stick my hand in the mouth of one of this catfish's cousins.

For nearly three years, I have tried to pin down a story on the fishy type of fishing known as handgrabbing, noodling, grabbling, grappling, stumping, hogging or dogging, depending on what part of the country you're in.

Two summers ago, a gentleman named Bubba said he'd help set up a handgrabbing trip for me on the Savannah River in eastern Georgia (which, like most states, considers fishing by hand illegal). But Bubba didn't come through.

Last summer, I thought I'd be grabbing in southern Tennessee, but my contact wasn't able to track down the grabbers along the river banks like he thought he'd be able to. And, he said, none of the grabbers had telephones.

I began to suspect handgrabbing was a myth, a colorful part of Southern folklore, the equivalent of snipe hunting -- a well-orchestrated hoax designed to make me look like a fool.

But that was before a reader e-mailed me the link to mississippihandgrabbing.com, before I spoke to Gerald Moore on the telephone, before I drove 450 miles just so a giant catfish -- or two, or three -- could bite down on my hand.

But that was before a reader e-mailed me the link to mississippihandgrabbing.com, before I spoke to Gerald Moore on the telephone, before I drove 450 miles just so a giant catfish -- or two, or three -- could bite down on my hand.

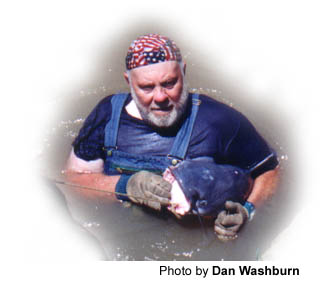

"Oh, it's for real. Trust me," said Moore, 56, known around Jackson as "the master," although he claims the nickname is more for his carpet-cleaning skills than his expertise as a handgrabber.

We were riding in Moore's truck on a back road west of Jackson, towing his johnboat to a remote private put-in along the Big Black, a tributary of the Mississippi River. In the backseat sat Preston Pittman, a world-champion turkey caller from nearby Canton, who was tagging along to videotape footage for an outdoors television show he hopes to launch in 2003.

Moore turned to me and, with the booming bass of a barker for a carnival freak show, said, "What you're going to see today will fascinate you."

Moore, of Madison, owns a carpet cleaning business now, but at various points in his life has been a police officer, a moonshine runner, a Harley-Davidson rider and a country singer. When I met him, he wore faded overalls and a faded blue T-shirt.

The American flag bandana he tied around his head drew attention away from his bright white beard. Moore could easily win an Uncle Jesse Duke lookalike contest, and I wouldn't be surprised if they still have that sort of thing in southern Mississippi.

When Moore showed up at my motel at 5:30 a.m. June 1, he told me he was up late the night before chasing after his three-legged dog. He caught him about a half-mile from the house.

Moore didn't look or act like a man who owned a computer, let alone a Web site. But it's at mississippihandgrabbing.com where you can buy "A Rare Breed ... The Masters of Handgrabbing," the video Moore made with friends Willoughby, Keith Lane and Ricky Liles.

Mississippi is the world's leading producer of farm-raised catfish. And Moore believes the state is likely the world's leading producer of handgrabbers, as well.

Mississippi is the world's leading producer of farm-raised catfish. And Moore believes the state is likely the world's leading producer of handgrabbers, as well.

"Of course you have to bear in mind, we're a bunch of rednecks here," Moore said.

The weekend before I arrived, a crew from CNN came out to go handgrabbing with the self-proclaimed masters.

"We've had all kinds of national attention," Moore said. "We've been on the NBC 'Today Show.' Turner South plays it about near every week. CNN? You can't get no bigger than that."

Folks are just plumb fascinated by handgrabbing which, by my count, is only legal in five states: Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana, Oklahoma and Tennessee. But I doubt people in the other 46 states really care. Handgrabbing isn't at the top of many to-do lists.

"It takes a special person to go in there and do it," Moore said. "Not that I'm a bad Joe or anything like that, but you've got to have that certain ..."

Moore finished his thought with a powerful grunt that, to me at least, made him sound very much like a bad Joe.

"You're basically fishing today and your hand is bait," Moore continued. "There ain't no rod and reel. There ain't no pole. It's man against fish."

Or water moccasin. Or snapping turtle. Or alligator. The Big Black River has them all. But usually, Moore assured me, handgrabbers only run into fish.

Or water moccasin. Or snapping turtle. Or alligator. The Big Black River has them all. But usually, Moore assured me, handgrabbers only run into fish.

And the fish can be feisty. You would be, too, if someone tried to interrupt your mating season. In Mississippi, it is legal to grab catfish from May 1 to July 15, the weeks when flatheads, and the more ornery blue cats, head to hollowed-out logs -- or, better yet, the cypress boxes placed throughout waterways by handgrabbers -- to spawn, a process that lasts a couple of days.

That's the time when grabbers like to shove their hands in muddy holes most people would never think of. And that's the time when catfish are more than happy to bite, which is ultimately the goal of the grabber.

Moore and his crew wear nylon gloves, the ones used for filleting fish, but they often don't stop the scrapes that leave scars. Catfish have thousands of tiny teeth that can rip off your hide like sandpaper.

"You catch one of them blue cats, and he can tear your (behind) up," Willoughby said. "People think we're crazy as hell."

I dug my foot into the floorboard of Moore's truck as we approached our put-in. I was thinking that those people might be right.

Part Two: Finger Food

June 6, 2002

Hawaii Spearfishing: To spear a fish, you must act like one

He is a predator of the sea, lurking deep beneath the surface, hiding inside cracks in the coral reef, waiting for dinner to swim by.

He is a predator of the sea, lurking deep beneath the surface, hiding inside cracks in the coral reef, waiting for dinner to swim by.

But Wendell Ko does not have gills. He cannot breath underwater. Although, at times it seems like he can.

Ko is a Hawaiian spearfisherman. He is also a freediver, which means when Ko plummets 100 feet into the Pacific to hunt a 100-pound fish, he does so with no scuba gear strapped to his back. The only oxygen tanks he travels with are his lungs.

"When you grow up with it, it just becomes natural," said Ko, 41, of Pearl City, a suburb of Honolulu. "If I'm stressed out at home or work, I go in the water for a couple hours of diving. It just totally relaxes you. It's a different world. It's amazing what the ocean can do."

I saw just what the ocean can do May 19. Ko and his 16-year-old son Justin let me tag along as they competed in the Chop Suey Meet, a spearfishing tournament put on by Alii Holo Kai, one of the top freediving clubs in Hawaii.

We met at Haleiwa Beach Park on the North Shore of Oahu at 7 a.m. After the divers were split into teams, the pairs headed off in cars and trucks in search of the piece of the Pacific that would yield the most fish.

We were told to be back by 1 p.m. for the weigh-in. The meet works on the honor system. Divers are expected to head into the ocean for their catch, not across the street to the painted sign labeled "Fresh Fish and Fillets."

We were told to be back by 1 p.m. for the weigh-in. The meet works on the honor system. Divers are expected to head into the ocean for their catch, not across the street to the painted sign labeled "Fresh Fish and Fillets."

The Kos and I traveled west and ended up setting off from the sandy shoreline behind a YMCA camp close to the northwestern point of the island.

Wendell Ko knows all the hot spots. He's been spearfishing the islands for 30 years. In middle school, he went without lunch for a month and used his meal money to purchase his first snorkel. His first spear gun was fashioned out of a cue stick.

Ko started spearfishing competitively in the 1980s and in 1999 he captained the Hawaiian team that won the U.S. national championship in Islamorada, Fla.

The fish caught in the Chop Suey Meet were sold in Honolulu the next day. The funds raised will help send this year's Hawaiian spearfishing team to nationals in California.

Ko outfitted me with everything for my maiden voyage. Wetsuit and gloves. Snorkel, mask and fins. He even handed me a spear gun and showed me how to load and reload the shaft. That was a skill that ended up going largely unused.

No use holding a gun if you can't hold your breath.

On our way to the water, we passed a sign that read, "No Swimming: Dangerous Current." I was the only one who seemed to take notice.

Spearfishermen have other worries ... worries with sharp teeth. Ko said that he encounters sharks on every other dive -- they can smell the blood of recently speared fish from miles away.

Every other dive? I asked Ko whether he saw a shark his last time out. He had, but somehow that didn't ease my concern.

"I've never seen the movie 'Jaws.' If I did, that would probably mess me up," Ko said, adding that spear guns can come in handy when a shark is circling.

If a spearfisherman does die in the water, it's usually not due to a shark. A phenomenon called "shallow water blackouts" can strike even the most experienced freedivers.

It often happens less than 15 feet from the surface. Expanding, oxygen-starved lungs literally suck oxygen from the diver's blood. The result is unconsciousness, and typically death.

Ko came close during a competition in 1996. After several deep dives, he stayed under too long, trying to catch a particularly crafty fish.

"I came up and I was all tingly," Ko said. "Everything turned black and white. I didn't know which way was shore and which way was out. I literally had to talk to myself."

We swam roughly 300 yards from shore, through the breaking waves to where the water was slightly less choppy. Because this was a competition designed for novices, we stayed in the shallows. The water was only 20 feet deep.

Out there, I could make it to the bottom OK. But by the time I did, my lungs were telling me that it was time to leave. But not Wendell and Justin.

Out there, I could make it to the bottom OK. But by the time I did, my lungs were telling me that it was time to leave. But not Wendell and Justin.

No, they stayed down there and made themselves at home, for minutes at a time. I suppose the best way to catch a fish is to act like one.

Spearfishermen are truly underwater hunters, using coral boulders as cover, tracking their prey. Sometimes divers make grunting noises to call in fish. Most kills happen at close range.

"The guy who knows the fish better, will catch more fish," said 58-year-old Alii Holo Kai member Dennis Okada, noting that many fishing "secrets" are kept within the ohana, or family.

"I feel it's the most selective method of fishing there is. Because you see what you are getting. You are not catching something you don't want to catch. You don't go out and shoot everything in sight."

Ko "selects" most of his fish at 60 feet or below. The deepest he has gone is 130 feet, the mere thought of which makes my eardrums bleed.

The first time you sink to 60 feet, Ko said, all the pressure feels like a simultaneous choke and Heimlich maneuver.

"But as you continue to dive those depths, your body gets used to it," said Ko, who has speared several fish that weighed more than 100 pounds. "So you don't feel the pressure any more. It's amazing what the human body can do."

I shot my spear gun once. And it was not a graceful attempt. It was a sloppy afterthought, a pull of the trigger on my way back up for a breath of air. The target was no fish in particular, just a school way out of range.

The sharp shaft, which is tethered to the rest of the gun, struck some coral and stuck there. At the surface, I tried to hold on, but the gun kept pulling me back under. I eventually had to let go. Justin went back down and got the gun for me.

Still, with two first place finishes, the Ko-Washburn team fared fairly well. We killed 10 fish between us. Wendell had five. Justin had five.

And I speared the rest.

Contact Wendell Ko by e-mail or visit www.freedivehawaii.com.