April 25, 2002

Clogging: A toe-tappin' good time

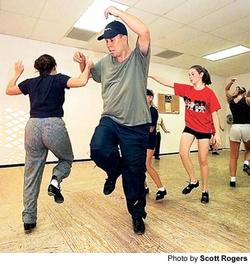

Keith Brady's feet went off like firecrackers. His knees were loose hinges -- swinging back and forth, up and around. Everything below was a blur.

Keith Brady's feet went off like firecrackers. His knees were loose hinges -- swinging back and forth, up and around. Everything below was a blur.

Perhaps Brady was a marionette, I thought. Perhaps someone, or something, was pulling at the strings from up above.

He made the unnatural appear natural. He made music with his feet. And then it was my turn.

"The good thing about clogging," said Brady, 35, instructor at the Storm Dancers studio in Oakwood, "there's no wrong step."

Brady, obviously, hadn't seen my steps yet.

Let's get one thing straight. Clogging has nothing to do with wooden shoes or windmills. It's a down-home dance, uniquely American.

But like most things born in Appalachia, clogging's roots reach back across the Atlantic. A little Irish. A little Scottish. Throw in some English. Some German, too.

It was the 1700s, and all the different folk dances fused into one. Unchoreographed. Free-flowing. Much like the lives of the South's early settlers.

"Clogging basically started as buck dancing," Brady explained.

"Buck dancing?" I responded.

"Buck dancing is," Brady began, "you go to a bar and see a bunch of guys that are, um, well lit. It has no structure to it. Just whatever they can stomp out."

Clogging eventually found its way to the flatlands, where it met with other influences, Native American and African-American dance among them.

Clogging continues to evolve today.

"People are making up new steps all the time," Brady said. "They take like half of an Irish step, half of a tap step and half of a Canadian step, put the three together and come up with something totally new."

"People are making up new steps all the time," Brady said. "They take like half of an Irish step, half of a tap step and half of a Canadian step, put the three together and come up with something totally new."

Several years ago, Brady himself helped invent a step during a particularly productive early morning at a bar in Pigeon Forge, Tenn.

It's called a "double-double." It sounds like a musical machine gun. And, I quickly realized, there was no way I was going to come close to accomplishing it.

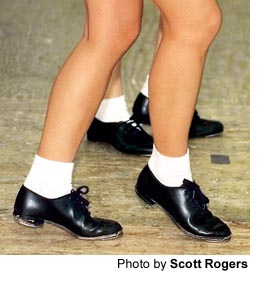

Clogging draws its name from the Gaelic word for "time." And the clog dancer, wearing shoes very similar to those worn in tap, is supposed to hit the floor on the downbeat.

I was just plain offbeat.

Brady and I were trying to boogie to the Doobie Brothers' "Steamer Lane Breakdown," and I stopped in mid-song. It just didn't feel right.

"That's one good thing about him," Brady said to the growing crowd at the studio (the presence of which likely played a factor in my faulty footwork). "He knows when he's not on beat."

Brady hasn't had that problem in some time. A Hall County native, Brady's family moved to Arcade when he was a young boy. When Brady was 12, he attended a clogging class at the town hall. He hasn't stopped stomping since.

"It was the thing to do," Brady said -- and for anyone who has ever driven through Arcade on the way to Athens, that statement is easy to believe. "It was the only thing you had to do in a little town."

By the mid-1980s, Brady, who performed locally with a group known as the Foot Stompin' Heel Clickers, was the best clogger in the world. Five years straight, he beat out 1,500 competitors to win the "Hee Haw" world championship at the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville, Tenn.

Now he spends his time teaching. At Storm Dancers, he has around 70 students from age 4 to 60. And they clog to anything from bluegrass to country to rock to hip-hop and pop.

"We do routines to all of it," said Brady, a land surveyor when he's not clogging. "When you start clogging to Britney Spears, that's when all the little girls come running saying, 'I want to dance like that.'"

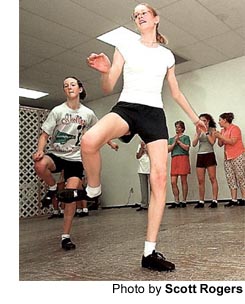

Thirteen-year-old clogger Taylor Soucie, an eighth-grader at West Hall Middle, remembers catching her first glimpse of clogging at the age of 5.

Thirteen-year-old clogger Taylor Soucie, an eighth-grader at West Hall Middle, remembers catching her first glimpse of clogging at the age of 5.

"It was fast," Soucie said. "I thought it was cool."

Kristi Pirkle, 16, who like Soucie is on Brady's performance squad, has been clogging for nearly two-thirds of her life.

"I don't play sports," the West Hall High junior said, "but I thought this was interesting. And it's good exercise."

Brady claims that 15 minutes of clogging is equal to seven miles of running. And if I had been able to last 15 minutes, I'd be able to tell you if he's telling the truth. You'll have to take Brady's word on this one.

I started out strong. I ended up shaky. The more steps Brady taught me, the less I felt I learned.

"I'm thinking too much," I said after realizing I had been sticking out my tongue in contemplation for the lesson's duration.

"Yep," Brady said. "You've got to relax and go with it. You can't think about it a lot."

I watched Brady's top class practice. I watched them relax and release. With the most experienced cloggers, it's as if the beat moves the body, not the other way around.

I liked it best when the music was off and the sound of shoes filled the room like a symphonic factory. Everyone was in step.

The worn wooden floor sagged with each collective stomp.

April 21, 2002

Garbage Collection: Are you 'garbage man material'?

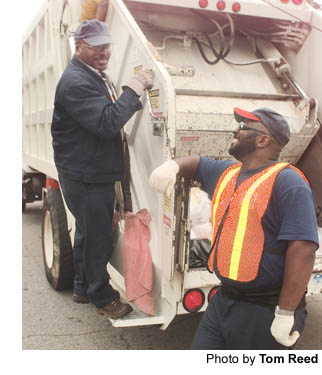

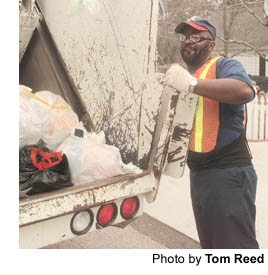

When Gainesville solid waste superintendent Adrian Niles explained it, the job description seemed simple enough. Get garbage out of can. Put lid back on can. Carry garbage to truck and throw it in the back.

When Gainesville solid waste superintendent Adrian Niles explained it, the job description seemed simple enough. Get garbage out of can. Put lid back on can. Carry garbage to truck and throw it in the back.

Repeat, again and again.

So that's what I did. For one day, I was a Gainesville garbage collector. And, you know, it wasn't as bad as you might think.

Sure, it smelled a bit, and I soiled a pair of slacks. But at the end of the day, I knew my body had been through a day's work. Real work. Sweat work.

We white collar types tend to forget what that feels like.

"It's a good, honest paycheck," 50-year-old Frank Hood, a garbage collector for two decades, said to me as we sat in the lounge of the public works building on Alta Vista Road in the minutes leading up to the 7:30 a.m. start of our work day.

Hood reminded me to wear my gloves -- it's easy to get stuck by syringes or broken glass -- and recommended that I carry along eye protection, too. He closed with a statement that took me by surprise: "It's fun. It really is."

Hood continued, "You meet a lot of different people out there. People who stay in a lot, they miss it all. When you're out there, you know what's going on."

Want to learn a little about your neighborhood? Ask your garbage collectors. You can learn a lot about people by carrying their trash.

Just judging by the size -- and the smell -- of the load you can determine someone's age, someone's eating habits. Garbage men know when new babies arrive (dirty diapers are a dead giveaway) and when children head off to college (the load becomes a lot lighter).

Just judging by the size -- and the smell -- of the load you can determine someone's age, someone's eating habits. Garbage men know when new babies arrive (dirty diapers are a dead giveaway) and when children head off to college (the load becomes a lot lighter).

Garbage men know when families move away and when others move in. And they take special notice of any new dogs in the neighborhood. You see, dogs don't differentiate much between the people who pick up the trash and the people who deliver the mail. They don't like either one.

Gainesville is a city that doesn't appear to have been laid out in any particular pattern. Streets criss and cross at odd angles. A single road can be known by several different names.

But it all makes sense in the minds of the garbage men. They drive these streets every day.

It's not just the streets, either. If you live in Gainesville, Richard Trammell, the driver of the truck that I worked on, likely knows where you hide your trash.

"I know where all the hot spots are," Trammell, 45, said with a chuckle.

Gainesville residents aren't asked to bring their trash to the curb. They aren't even asked to bring it to the front of the house. Garbage collectors are expected to collect the garbage from wherever it is kept.

And that could be behind a big tree in the backyard or behind a fence next to the garage.

The level of service shocked Dick Young when he moved to Gainesville from Dekalb County last year. He made a point to say hello to Trammell and my truck's other "toter" Darrell Carter when we pulled up next to his house.

"These guys are great," Young, 67, said. "They are so helpful, too. I never heard them complain, and that's unusual. I wouldn't mind having to bring the trash up myself. I would do it if it came to that. But for them to go around back and pull it out, I think that's terrific."

It's a nice service. I agree. But after eight hours of tramping up driveways and through backyards in search of trash, my aching legs had a different opinion.

The average Gainesville garbage collector -- of whom there are 20, responsible for nearly 5,000 city residences -- walks six miles a day.

"It's just go, go, go," Niles said. "It keeps 20 busy. It's stop and go. It's uphill and downhill. It's hopping off the truck and hopping back on."

Some guys don't even make it through the first day. It's too hard, too smelly, too messy. They radio back to the office and ask to be picked up by the side of the road.

"Even with a garbage toter, it takes a special kind of person that wants to do this work," Niles said. "You would think anybody could do it, but it does take a special kind of person."

Riding on the back of a garbage truck is strangely liberating. Lean back a bit and the wind hits you in your face. It makes you feel like you're flying -- and neutralizes some of the truck's odor.

I also found pleasure in operating "the blade," the mechanical door that sweeps the trash inside the truck. In a matter of minutes, an overflowing load vanishes. All that is left is a foul soup -- milk, grease, blood and other liquids and juices whose expiration dates have come and gone. The vile brew drips down the blade and settles in a big black puddle.

I also found pleasure in operating "the blade," the mechanical door that sweeps the trash inside the truck. In a matter of minutes, an overflowing load vanishes. All that is left is a foul soup -- milk, grease, blood and other liquids and juices whose expiration dates have come and gone. The vile brew drips down the blade and settles in a big black puddle.

Oh, and then there's the smell. There's always the smell.

Trammell, Carter and I eventually settled into a rhythm.

"We've got to go get it," said Carter, 34, toting for a little more than a year. "No matter what, rain or snow, we got to go get it. It's our job. That's how we look at it. We work as a team to get this thing done."

When Trammell would stop the truck, I'd look to his face in the side-view mirror. A nod meant it was my turn.

"Go to that white house," Trammell said on one of our early stops. "It's going to be around back. He's got some white bags on his patio."

Sure enough, Trammell was right. And the old man who keeps white bags of trash on his patio was smoking an early-morning cigarette on his screened-in back porch.

"You're a new guy, ain't you?" he said to me.

"Yep," I responded. "It's my first day."

"Well, hang in there. You can retire in about 80 years." The old man laughed.

True, the job of garbage collector is not one people usually plan for themselves. It just kind of happens.

Garbage toters in Gainesville start out at $7.69 an hour. But there's room for advancement. Trammell has been doing it for 21 years, and he's moved from the back of the truck to the driver's seat.

"You would think that out of all the other jobs I had, that they would have been better for me than doing this here," Trammell said. "It's one of the worst jobs in the world, I guess, and I done stuck with it this long. It does have good benefits, though. That's one thing that kept me here this long. And the hours are really good."

We took our only break of the day at mid-morning. By that time, the gloves I wore were no longer white. We sat on the curb at a gas station and ate a snack. The break didn't last long.

Streets and houses ran together as the day wore on. It all started to look the same to me.

Streets and houses ran together as the day wore on. It all started to look the same to me.

Get garbage out of can. Put lid back on can. Carry garbage to truck and throw it in the back. Repeat, again and again.

Sometimes the monotony is broken. Perhaps you come upon a dead dog covered in maggots -- yep, some people throw those out with the trash -- or an appliance that is still in working condition.

Trammell remembers one time when a homeless man emerged from a Dumpster that was about to be emptied into the truck.

"We almost killed him," Trammell said.

Garbage men are blue-collar magicians. They make things disappear. We often bag up our trash, put it outside and then forget about it. It goes away twice a week. We take it for granted.

"Sometimes a customer will tell me I'm doing a good job," Carter said. "And I take that and say to myself, 'It's going to be all right.'"

I was worried that I might slow Trammell and Carter down, but we made good time. We finished our route and made it back to "the house" with minutes to spare.

"You're garbage man material," Carter said to me with a wide smile. "If you can hang for the day, you're garbage man material."

I took it as a compliment.

April 13, 2002

Remembering Nell: Someone to watch over me

My dear old next door neighbor, Nell Thompson, passed away Sunday. And I didn't even realize it until Wednesday afternoon. I've spent the long hours since trying to figure out how that could happen.

My dear old next door neighbor, Nell Thompson, passed away Sunday. And I didn't even realize it until Wednesday afternoon. I've spent the long hours since trying to figure out how that could happen.

I learned of the sad news while reading the newspaper. I saw Nell's name and face on the obituary page and threw down the paper in disbelief. Then I read further, and I threw down the paper in disgust.

I had missed Nell's funeral. I had been playing basketball instead.

I felt awful. I felt guilty. So I started to write. That's all I knew to do.

Nell and I didn't have much in common when I moved here in the fall of 1998. She was in her 80s, a lifelong resident of Hall County. I was in my mid-20s, a transplant from up north.

But we were neighbors. And in certain parts of the country, that still means something.

It's clear to me now that the neighborly relationship Nell and I shared was an important part of my existence here in Gainesville. It was a constant I could always count on. But I don't think I ever expressed the importance of our friendship to Nell.

Nell, who was 84 when she died following a sudden illness, lived alone in a home on Hillcrest Avenue just a few feet from mine, but our paths didn't cross as often you might think. Journalists and senior citizens don't keep the same hours.

When we did see each other, we'd always stop to chat.

I'd emerge from my house at midday to retrieve the newspaper from my steps and Nell would be raking leaves or pulling weeds -- she loved working in her yard, as much as her aged body would allow. Sometimes we'd go to our mailboxes at the same time.

Nell would always wave me over. Nell always wanted to talk.

"How's your mom and them?" she would ask.

We talked about the weather a lot. Nell was always worried that a bad storm was going to knock a tall tree through the roof of her tiny home.

On the surface, our conversations never had much substance. Nell just seemed happy to talk about anything.

Nell said she felt safe with me living next door. And she kept a watchful eye over me, as well. She noticed when my car was gone for long periods of time, and would always call me upon my return.

She'd never leave a message, though. Nell didn't care for answering machines.

Nell liked that I wrote for the newspaper. I interviewed her for a story I did during the ice storm in February 2000. Our street was without power for the better part of a week, and I found Nell wrapped in blankets in front of her gas-powered fireplace sipping coffee she had heated campfire-style in the flames.

The story appeared on the front page. Nell said I made her a celebrity over at the senior center.

Nell seemed to take comfort in the fact that she could see her neighbor's photograph in the paper each week, even if sometimes she couldn't remember what day my Sporting Life column appeared in The Times.

"I haven't seen your picture in the paper the last couple Mondays," Nell said to me last year.

"Nell, my column runs on Tuesdays," I replied.

Nell thought about it. "Always has?"

"Yes."

"Now you're not going to tell me I'm getting old, are you?" she said with a laugh and a pat on my arm.

Yes, Nell was getting old. She liked to remind me of her age and her assorted maladies. But she was very proud that she lived on her own, that she still worked in her yard, that she still drove herself to church and the grocery store.

Every day, Nell walked up and down our street. Doctor's orders.

I saw Nell walking last week. A surgical mask covered her face. I waved from my car. I'm pretty sure she saw me. I'm pretty sure that was the last time I saw her.

Nell rarely asked for help with anything. But when she did, I was happy to do what I could.

I remember last December, she asked me to carry her porcelain Christmas tree from her basement to her living room. She had made the tree several years ago and didn't trust herself with it.

Even for a small gesture like that, Nell was most appreciative. Now, I am left thinking I could have done much more for Nell while she was here.

But Nell was always thankful for anything. She'd often tell me she didn't know what she would do if I ever moved away. Now, I wonder what I am to do now that she is gone.

Nell's car is still parked in front of her house. Her rake is still propped up against the side wall.

I walked outside to fetch my mail Thursday and glanced toward Nell's house. Part of me expected her to emerge from her front door, too.

I waited. But it never happened.

April 11, 2002

Team Penning: Not just horsing around

John Hulsey remembers riding his horse down Green Street. He'd clip-clop on over to the old Royal Theater, which used to occupy the vacant lot next to Clore's Restaurant. He'd tie up his horse and take in a movie.

John Hulsey remembers riding his horse down Green Street. He'd clip-clop on over to the old Royal Theater, which used to occupy the vacant lot next to Clore's Restaurant. He'd tie up his horse and take in a movie.

This was the 1960s -- not too long ago, really. Back then, Gainesville was more Wild West and less Atlanta. Back then, Gainesville was horse country.

And now, Hulsey sees the area experiencing a rebirth in all things equine.

"It's really mushrooming again," Hulsey, 49, of Gainesville, said. "It kind of brings people back to older days."

The sport that brought Hulsey back to horses is team penning. He picked it up a little more than a year ago, and now he can't get enough.

Team penning is similar in several ways to the horse sport of cutting. But penning is pushy. It's more offense than defense.

And in penning, the cowboys -- and cowgirls -- make a heck of a lot more noise.

Here are the basics: A herd of 30 cattle, numbered "0" through "9" three times over, settles at one end of an arena. As a team of three people on horseback approaches the herd, the public address announcer calls out one of the numbers.

The three cattle wearing that number become the targets. The riders must separate them from the herd and get them into a small pen at the far end of the arena in less than 90 seconds. The fastest time wins.

"I've had just about every hobby there was in the history of the world," Hulsey said. "And I've had more fun doing this than anything I've ever done. It's a rush. It's wide open. It's fast."

Well, it's supposed to be fast. But two weeks ago, during my first penning lesson at Hulsey's farm in White County, I was more slowpoke than cowpoke.

"You're not from around here, are you?" asked Hulsey's penning pal Devin White. The 20-year-old Gainesville High graduate, a horseshoer by trade, insisted he was referring to my accent and not my riding style. That, he tried to blame on the horses.

Hobo. Leo. Rusty. I rode them all that morning. Sometimes, the horses wouldn't go the direction I thought I was directing them. Other times, they wouldn't go much at all. Hulsey remarked that he had never seen Rusty so reluctant to run.

I knew what the problem was. And I'm fairly certain Hulsey and White knew it, too -- they were just too nice to say it. The problem was the rider, not the ridee. But they still kept swapping out horses on me anyway.

No matter. Any horse can sense when a rider is tense.

And I had good reason to be. Penning is not intended for the novice rider. It involves sudden starts and stops and flat-out sprints. Even the most experienced riders can end up in a heap on the ground. That is part of the draw.

So are belt buckles.

Hulsey and White -- along with a few other local residents, including Hulsey's stepdaughter Crista Ragsdale -- are regulars at the weekly team penning jackpot contests at Mike "Curly" Phillipsâ Cherokee Rose Arena in Carnesville.

It's the only show for miles. Every Saturday, penners from across the Southeast -- Florida, Tennessee, Alabama, South Carolina, North Carolina and, of course, Georgia -- come to ride at Curly's.

"Curly's is a place the pros come to practice," White said. "It's people that run the circuit. This is where you're going to get to ride with the best around here in the Southeast. They all go to Curly's."

"Curly's is a place the pros come to practice," White said. "It's people that run the circuit. This is where you're going to get to ride with the best around here in the Southeast. They all go to Curly's."

"We just want to win," Hulsey added. "We're paying $10,000 to win a $175 belt buckle."

"But you won it," White said with a satisfied smile. "You didn't buy it."

The "Spring Fling" belt buckle series at Curly's is currently at its halfway point, and Hulsey and White are both running in the top-10 in the points standings.

I went and watched them a couple of weeks ago. I got there at about 6 p.m. and left at 11 p.m. The riders kept riding for several hours after that. There is money at stake, but not much. Each event pays out 60 percent to the winners. Entry fees max out at $15.

"They just love it," said Curly, who plays the role of announcer, herder, plowman and janitor for these rodeos he's been running for the past dozen years. "It's probably the most fun you can have with your clothes on."

It's not too bad for the spectators, either. At Curly's, the cattle are always "fresh" -- meaning frisky -- and successful runs are the exception rather than the rule.

You see, the riders have more than just the 90-second limit to deal with. There is a "foul line," too, typically the halfway point of the arena. Teams are disqualified if they let cattle of the wrong number break from the herd and cross the foul line. Same result if cattle chased toward the pen somehow sneak their way back across the foul line.

That makes for some desperate dashes ... and savage screams.

"Hey! Hey! Hey! Get back there, you darn cow!" the rider yells, body angled sharply forward, hands steering horse like a stock car.

It was chilly that night at Curly's. Steam rose from the heads of hot horses. But some hot cocoa and a quesadilla from Judy Brown's kitchen hit the spot. And riders know, cold doesn't last long in Georgia.

"In the summer, God it's dusty," Hulsey said as he waited for his next run. "It's hot and you'll be out here until 2 o'clock in the morning. And then you've got to drive all the way back. And then you've got to get up and go to church.

"It's rough. But it's fun."

And you can always use a new belt buckle, right?

Cherokee Rose Arena

Where: Carnesville

When: 6 p.m. Saturday

What: Year-round competition in team penning, sorting and one-on-one.

Entry fees: Range from $5-$15. Events pay out 60 percent to winners.

Contact: Mike "Curly" Phillips, (706) 335-7481

Directions: From Gainesville, take U.S. 129 south to I-85 north. Proceed 17 miles on I-85 to the Ga. 63/Martin Bridge Road exit, number 154. Turn right onto Martin Bridge for .2 miles and turn left onto Ga. 59. Travel 2.3 miles and turn right onto Bold Springs Road. After 5 miles, turn left onto an unnamed gravel road marked by a small "Cherokee Rose Arena" sign. Bear right at fork in road. Arena is on left.

April 4, 2002

Zamboni Drivers: The ice men cometh

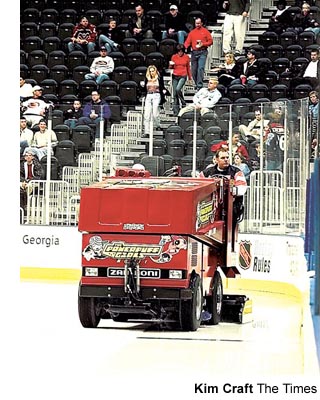

It is a movable throne. In it sits the king of the common man. He is the Zamboni driver.

It is a movable throne. In it sits the king of the common man. He is the Zamboni driver.

The Atlanta Thrashers won only 19 of their first 76 games this season. That's the worst record in the National Hockey League.

But the Zamboni drivers at Philips Arena can do no wrong. They are cheered every time they take the ice.

Perhaps this happens because Thrashers fans, like the followers of any franchise in its infancy, are in desperate need of something to get excited about. Or perhaps Americans just love anything with four wheels and a motor.

Either way, Matthew Krull isn't complaining.

"I'm the kind of person, I need my 15 minutes of fame every once in a while," said Krull, 28, of Crabapple, who has been one of the main Zamboni drivers at Philips since the Thrashers got their start in 1999. "I really get a thrill out of it."

He's not the only one. During Thrashers games at Philips, a lucky fan gets to ride shotgun for every Zamboni run around the rink. They wave to the crowd, pump their fists and give the Zamboni driver high-fives.

"Everybody wants a ride," said 28-year-old Javits Britt, who hitchhiked to Atlanta from Ann Arbor, Mich., three years ago to become a Zamboni driver for the Thrashers. "Or they want tickets. Or they want a puck."

"Everybody wants a ride," said 28-year-old Javits Britt, who hitchhiked to Atlanta from Ann Arbor, Mich., three years ago to become a Zamboni driver for the Thrashers. "Or they want tickets. Or they want a puck."

But mostly people ask about the Zamboni ... or whatever they choose to call it.

"So many of them butcher the name," said Chuck Robinson, 43, of Jefferson, known officially around Philips as the assistant director of building operations. Unofficially, people call him "the ice guy."

Stromboli. Zucchini. Cambodia. Robinson has heard people mangle the word Zamboni several ways in his 23 years working at ice rinks.

Whatever word they use, people seem mesmerized by the two massive machines that make rough ice glassy again between periods at a Thrashers game.

"We kind of feel like we're putting on our own little show out there," Robinson said.

But the performance is not without purpose.

"Fans don't really understand how important the ice is," Thrashers defenseman Brian Pothier said. "They just think that we go out there and ice is ice. But if you have a crew that takes care of the ice well, it's really important to the team.

"Here, it's great, especially for the southern climate. You would think that the humidity and the hot weather would kind of mess it up. But here, it's just as good as any sheet of ice up north."

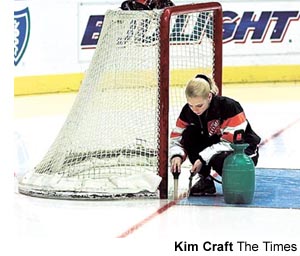

Robinson is an Atlanta native who has spent most of his adult life making ice, a warm-weather guy who spends most of his days in the freezing cold. He manages an ice crew of 10, mostly part-timers. They include Zamboni drivers, snow shovelers and the people who make sure the holes that hold the goals don't freeze over.

"Yeah, it's a novel job," Robinson said. "Certainly nobody else in the city does it. Not too many people in the state do it."

Robinson paid his dues in community rinks in Atlanta, Orlando, Cincinnati and Pittsburgh before landing his current gig, ice guru for his hometown hockey club.

"You can't go much higher than this, really," Robinson said. "Maybe if you were the Zamboni driver for the Toronto Maple Leafs, that might be a little more prestigious."

The NHL prefers the term "ice technician," because ice guys do much more than drive a Zamboni, especially on game days.

"It's an all-day job," Robinson said. "It's a 16-hour investment from start to finish."

"It's an all-day job," Robinson said. "It's a 16-hour investment from start to finish."

March 27, I tagged along with Robinson and his crew as they prepared Philips for the Thrashers' 7:30 p.m. game against the Minnesota Wild. When I arrived at 4 p.m., Krull had already been on the job for nine hours.

The ice was filthy when he got there. It had been covered up for nine days. Philips is a multipurpose arena. In addition to the Thrashers, it's home to the National Basketball Association's Atlanta Hawks, Arena Football's Georgia Force and several major music concerts.

Underneath it all, the ice remains. It's only cover, some pieces of plywood.

So step one is scraping the ice surface free of everything that shouldn't be there -- gum, beer and half-eaten hot dogs included.

Sometimes just scraping doesn't cut it. Robinson recalled a time when members of the rap-metal group Limp Bizkit spilled an entire bottle of something alcoholic that seeped deep within the hockey floor. A circular saw had to be used to remove the stained section of ice.

The ice, actually, is less than an inch thick for Thrashers games. The floor design is painted on top of two thin layers of ice and then encapsulated by more layers of ice, including the playing surface.

After clearing the floor of debris, Krull spent the rest of the morning rebuilding the ice with the Zamboni, which, by the way, got its name from the man who invented it. Frank Zamboni made his first self-propelled ice resurfacer in 1949. Prior to that, ice rinks relied on carts pulled by horses or tractors -- and a lot of guys with shovels.

The Zamboni is much more than just an ice polisher. It shaves the ice and picks up the snow. It washes the ice and smoothes the surface. Then it spreads a layer of clean hot water -- more than 160 degrees hot -- over the ice.

The hotter the water, the clearer it freezes. And in about four minutes, about the amount of time the Zambonis are allotted between periods, the ice is hard enough to skate upon. That's because of the concrete slab underneath, which features nine miles of pipes filled with chemicals that are constantly cooled to 17 degrees.

That makes for some cold working conditions. You feel it first in your feet (Robinson wears thermal socks to work), and then it spreads. It stays with you, too.

"You wake up and your bones are just cracking," Krull said.

But cold is part of the job description when you're working with frozen water. Robinson said his crew has a "passion for ice." And that usually starts with a passion for hockey.

"It makes me feel more a part of the sport," said Britt, whose favorite perk is his permanent front-row seat for the games. "If you're a hockey fan, it doesn't get any better than this."

"It makes me feel more a part of the sport," said Britt, whose favorite perk is his permanent front-row seat for the games. "If you're a hockey fan, it doesn't get any better than this."

The goal of the Zamboni driver is to create the perfect sheet of ice, smooth and safe, every time. When dealing with a liquid and ever-changing atmospheric conditions, even indoors, that's easier said than done.

"The reality of it is, ice is a tough situation to make perfect," Robinson said. "If they would give us 15 or 20 minutes, we could get awful close. But who wants to sit through 15 or 20 minutes of Zamboni driving?"

Robinson might be surprised.

"The Zamboni is the best part," said 13-year-old Thrashers fan Alex Shilling, of Alpharetta. "It's cool how they're so synchronized."

It can be rather hypnotizing, I found. I watched the Zamboni work from several vantage points last week -- the passenger seat, the front row, the upper deck -- and I found pleasure in each one.

With each pass, rough becomes smooth, old becomes new. The Zamboni has a way of erasing the past. And in the Thrashers' 4-2 loss to the Wild, there was plenty worth forgetting.

Seated in the press box, up near the roof, I watched the arena lights reflect in the Zamboni's shiny wake before the second period began. And then I watched players come out and scratch it all up again.

That's the part that makes Robinson smile.

"It's great," he said. "That's what it's there for."