February 28, 2002

Bingo: Trying to be chance's chosen one

When Bernie Olejnik took his seat behind the Bingo King Autotronic 7600, everybody shut up. Many in the crowd of nearly 100 at the Gainesville Elks Lodge on Sunday had been waiting more than an hour for this moment -- waiting patiently for that first bright numbered ball to separate itself from the pack, waiting for the bingo to begin.

When Bernie Olejnik took his seat behind the Bingo King Autotronic 7600, everybody shut up. Many in the crowd of nearly 100 at the Gainesville Elks Lodge on Sunday had been waiting more than an hour for this moment -- waiting patiently for that first bright numbered ball to separate itself from the pack, waiting for the bingo to begin.

They arrive early for a reason, I learned. There are lucky seats to be secured, lucky trinkets to arrange on the table. Bingo players are constantly trying to change the course of chance.

And each game, one or two of them do. There's always a winner in bingo. That's how the game sucks you in.

Olejnik didn't have to call out many numbers for me to remember why as a child I used to spend so much time in the bingo tents at the Bloomsburg Fair back in Pennsylvania.

I used to plunk my quarter down and play, anxious to win something, anything. Perhaps some plastic mixing bowls or a set of steak knives. I rarely had any use for the prizes, but I always found winning to be wonderful.

The bingo cards at the fair were thick and worn on the edges. We used peanuts as markers.

Compared to bingo at the Gainesville Elks, that old set-up seems like, well, peanuts.

Cards are slick sheets of paper and used only once. Plastic bottles full of ink, known as "dobbers," make the marks. Some players even tote their personal dobber collections around in hand-knit carrying cases.

Prizes given away every Sunday at the Elks made the steak knives of my youth seem rather silly.

Nine games pay out $1,100, $600 of which is for a single game known as the "jackpot." The Elks, actually, would like to offer more prize money, but Georgia law won't allow it.

"We can't do near what the Indians can do up in North Carolina," said Ron Harlan, former Elks exalted ruler and current chairman of the bingo committee. "That does cut into our business a bit. The real avid players will go up there."

Still, the Elks take in around $1,500 from bingo each weekend. That's enough to keep several charities happy.

And the stakes are high enough to keep a rather large crowd of regulars coming back each week.

And the stakes are high enough to keep a rather large crowd of regulars coming back each week.

Max and Marion Paton, who raise breeding chickens on their farm in Dawsonville, rarely miss a Sunday afternoon of bingo. Max is 82. Marion is 80. They'll be married 59 years in April.

"Oh yeah, we have a lot of fun," said Max, a World War II veteran. "We enjoy it. This is like entertainment."

"And," Marion offered, "they do as a whole have very nice people here."

Added Max, "You don't get a bunch of fibbers."

The Patons always try to grab the table that straddles the barrier between the smoking and non-smoking rooms. They don't care for the smoke -- and there is plenty (you should smell my clothes) -- but they also don't like to be out of view of the Bingo King Autotronic 7600, either.

And the Bingo King Autotronic 7600 sits in the smoking room, because that's where most of the bingo players sit. The two habits seem to go hand in hand.

The Bingo King Autotronic 7600 looks like something out of a 1960s sci-fi movie, like one of those handwriting analysis machines you find at local carnivals.

Through the machine's window, you can watch the bingo balls toss about, and get sucked to the top one by one. Where the balls pop out, a video camera awaits. The current ball is broadcast to several televisions positioned throughout the bingo room.

Then Olejnik makes the call. "Next number. Under the 'O.' Sixty-four. That's 'O' six-four." The number lights up on the big board behind Olejnik and the Bingo King Autotronic 7600.

This is definitely not the Bloomsburg Fair.

But the game still plays the same. You still need your numbers to be called. You still need them to occupy the right combination of squares on your card.

They didn't for Max. "I'll be a son of a gun," he said again and again. "They're all in the wrong places."

But they did for Marion. Olejnik called out "I 28" and Marion called out "Bingo!" So did several others. They each won $16.70.

You can tell when a game of bingo is coming to a close. The crowd senses it. With each number called, anticipation grows. You feel your time is running out. There is a murmur. Then there is a winner.

You can tell when a game of bingo is coming to a close. The crowd senses it. With each number called, anticipation grows. You feel your time is running out. There is a murmur. Then there is a winner.

"I get very excited when I win," said Joyce Head, 55, of Murrayville. "It's like a shot. I mean really, it's like one. It is."

Head "gave up smoking and took up bingo" several years ago. One can be as addictive as the other. On Saturday, Head headed up to Rock Hill, S.C., for some high stakes bingo. She didn't win, but said she knows she will again soon. She likes to think of her bingo card as half full, not half empty.

"I go expecting to win," Head said. "I mean you've got to be there. You can't win sitting at home."

How about sitting on a horseshoe? B.T. Hudgins does that.

"Anything to help out," the Gainesville resident said. Hudgins and friend Jean Bachelor also carry around buckeyes in their pockets for luck.

Others will place troll dolls, four-leaf clovers or other knickknacks before them for good fortune. Elephant figurines are supposed to work, too ... but only if the trunk is pointing up.

Some feel the only way to increase the chance of winning is to increase the number of bingo cards. I watched one lady play 39 at once. I had enough trouble with six.

Betty Ladewig, a 74-year-old from Murrayville, had 27 cards in front of her and nothing else. She doesn't believe in good luck charms.

And she won one of the $600 prizes last week.

"I think it's all dumb luck," she said. "But I like to gamble."

Perhaps I do, too, Betty. I'd think I got my 10 dollars' worth of excitement on Sunday.

One time I was a "B 2" and a "B 9" from winning $100. I felt a rush overtake my body.

Then again, maybe it was just the cigarette smoke.

February 21, 2002

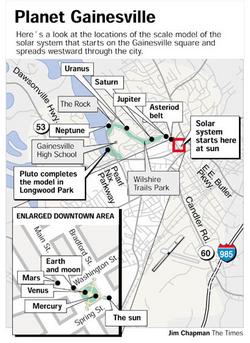

Solar System Walk: No telescope required

Robert Webb told me to meet him at the planet Earth. So I did. It was cold and windy there.

Robert Webb told me to meet him at the planet Earth. So I did. It was cold and windy there.

Turns out Earth is on the corner of Washington and Main.

You'll find the moon there, too. Look toward the courthouse, and you'll see the sun. It's a stainless steel ball 27.5 inches in diameter.

Gainesville is home to one of the United States' only walkable scale models of the solar system. It's 1.8 miles from the sun to Pluto, which is tucked away in a far corner of Longwood Park. The rest of the planets dot a path that meanders through Rock Creek Park, Ivey Terrace Park and the Wilshire Trails system.

This universe was created in less than two years. The process began during the total eclipse of the sun -- the real sun -- in February 1998. Members of the North Georgia Astronomers club brought telescopes to the Gainesville Square for the occasion.

They let passers-by have a look, too. And they tried to answer their questions.

On a day when the sun and moon appeared to be identical in size, it was difficult for many to comprehend that a hollow sun would actually hold more than 64 million moons. You see, the astronomers tried to explain, the moon is only 245,000 miles away from the Earth, while the sun is 93 million miles away.

All those zeros led to some blank stares.

"We tried to figure out something we could do to try and make all of these numbers seem a little more real," said Webb, president of the astronomy club.

So the idea for a scale model of the solar system was born.

And why not? Gainesville is already home to a bronze chicken monument and a statue of Old Joe, a Confederate soldier who really is a Rough Rider from the Spanish-American War. A few planets surely wouldn't make things any more peculiar.

The solar system plan went through a few revisions before it came to fruition, however. At first, Webb and his group considered painting the circle that surrounds Old Joe yellow, to signify the sun.

"It seemed like a good idea," Webb recalled. "But when we got home and got the calculator out, we found out that the next planet would be in Oakwood. Pluto would have been in Chattanooga."

So they shrank their sun and came up with a workable, and walkable, equation: one mile on Earth equals 2 billion miles in space. It fit perfectly, from the square to Lake Lanier.

After a brief squabble with members of the local chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, who didn't want Mars and Venus encroaching on Old Joe's personal space, the astronomers got approval for their plan. The 70-member club then became incorporated so it could accept tax-deductible donations to fund the $30,000 project.

"It was kind of a big step for our little club," said Webb, a boat mechanic with a bushy beard.

"It was kind of a big step for our little club," said Webb, a boat mechanic with a bushy beard.

The Earth and moon monument was put in place Dec. 31, 1999. Several more were erected two days later. The sun came February 2001. The project was complete by April 2001.

It was a nationwide endeavor. Elberton granite was used for the monuments. Plaques were made in Virginia. Ball bearings used for some of the planets came from Connecticut. Gemstones used for other planets were shipped in from California and Oregon.

An outfit in Ohio supplied the sun -- "That's the only place I could find that would do big stainless steel hemispheres," Webb said -- which was welded together by a guy who builds dragsters in South Carolina.

The sun is by far the most noticeable of the planets in the scale model. That's because it's also by far the biggest. In comparison, the Earth is a quarter-inch in diameter. Mercury is the size of a nail head. An asteroid on the monument near the Hall County Library is a barely-visible speck. But it's there. And it's made out of an 18-thousandth ball bearing.

The speed limit of the universe is the speed of light. Webb and I broke the law. We walked to Pluto and back in about two hours.

Our starting point was the sun, whose surface has been buffed. Turns out the reflection of the real sun was blinding.

Mercury is just a few paces away. After the "Old Joe eclipse," you'll find Venus and the Earth and moon. And so on and so forth. Just follow the comets painted on the ground that mark the path.

Most of the planets have sponsors, some more fitting than others. For example, Venus, the only planet named after a goddess, is sponsored by Brenau Academy, the city's private boarding school for girls. The sponsor for Mars, named for the Roman god of war, is Riverside Military Academy.

"We tried to do all the tie-ins we could," Webb said.

I learned a lot during my celestial stroll. Like the fact that our days of the week got their names from the planets, the sun and the moon. Some -- like Saturday, Sunday and Monday -- are more obvious than others.

I also learned that Saturn is located really close to my house.

"No matter what age you are or how much you know about it, you get a little bit out of it each time," Webb said. "The best feeling for me is actually seeing people use it."

Sure enough, right around Uranus, we happened upon Paul Johnson and Jason Martin, two North Georgia College & State University students doing the solar system walk for their astronomy class.

"You get a good feel for how big things actually are by walking it off," Johnson said.

It does really kind of put everything in perspective. We are small and insignificant, a small ball bearing floating in the vast cosmic toolbox.

When you arrive at Pluto in Longwood Park, another monument stands beside it. It directs you toward the star Alpha Centauri, the next thing you would encounter on your hike through a scale model of the universe.

But if you plan on going there, bring along your bathing suit. You won't hit Alpha Centauri until you're swimming in the Indian Ocean off the coast of Australia.

February 14, 2002

Surgery Room: Dunahoo's knee troubles double

Johnson High sophomore Megan Dunahoo was screaming. She lay on the basketball court clutching her right knee. Yes, Megan, again.

For the second time in less than a year -- almost a year to the day, in fact -- Dunahoo suffered a season-ending torn anterior cruciate ligament in her knee.

This year, it was her right knee. Last year, it was her left.

This year, it happened Jan. 18 in the second quarter of the Knights' junior varsity game against Fannin County. Last year, it happened Jan. 19 ... in the second quarter of the Knights' junior varsity game against Fannin County.

"The second time is a lot more frustrating," said Dunahoo, who was sidelined for six months by her first torn ACL. "Because you think why does it have to happen to you twice. But, I don't know, everything works for a reason in God's plan. I have faith and I know that I'll be OK."

Dunahoo is one of four Johnson players -- and one of eight high school girls in Hall County -- to tear an ACL this season.

Neither of Dunahoo's ACL injuries was caused by contact. She tore her left while making a cut for a pass. She tore her right while defending on the full-court press.

Neither of Dunahoo's ACL injuries was caused by contact. She tore her left while making a cut for a pass. She tore her right while defending on the full-court press.

"As I lunged, I felt it pop the other way," Dunahoo, 16, said.

Already a veteran of torn ACLs, Dunahoo knew that she had just done it again. And she knew well the long road to recovery she was set to travel.

"I'm not dreading it, just cause I've already been through it and I know what to expect," Dunahoo said Feb. 6, five days before her surgery. "I guess I'm ready to get it over with. I'm ready to be off crutches, walking around and doing the rehab and getting back."

Last Saturday, Dunahoo was a member of the sophomore court at Johnson's Sweetheart Dance. She danced on her injured knee -- in high heels, no less.

"It didn't hurt," Dunahoo said. Torn ACLs can be deceiving.

All in the family

At 6:45 a.m. Monday -- 45 minutes before Dunahoo's surgery -- Emory Dunahoo Jr. was at his daughter's bedside at the HealthSouth Gainesville Surgery Center. He knows a thing or two about bad knees.

Emory has had four knee surgeries and is awaiting a fifth, a total knee replacement. He blew out his left knee playing football for North Hall High in 1973. He's been paying for it ever since.

"I tore the ACL, the PCL (posterior cruciate ligament), everything in it," said Emory, who can barely bend his left leg. "Megan might decide to play next year, she might not. But 30 years from now, I don't want hers to be like mine where it hurts all the time."

The eldest Dunahoo daughter Lindsey, 18, has had her knee scoped, as well. Fourteen-year-old Josh, the youngest Dunahoo and a football player, has been surgery-free so far.

"Some of it is definitely genetic," Dunahoo's orthopedic surgeon, Robert Jennings Jr. of Gainesville, said. "Whether it is genetic as far as the way that they move or genetic as far as the way the knee is built and the ligament composition, I don't know."

Jennings, 40, is a Gainesville High graduate who studied at Duke University, the University of Virginia, the University of Wisconsin, and the American Sports Medicine Institute in Birmingham, Ala. He returned home to practice medicine and is now one of the area's most respected surgeons.

Jennings, 40, is a Gainesville High graduate who studied at Duke University, the University of Virginia, the University of Wisconsin, and the American Sports Medicine Institute in Birmingham, Ala. He returned home to practice medicine and is now one of the area's most respected surgeons.

He repaired more than 70 torn ACLs last year alone.

"We've done enough of them that it's pretty routine for us," Jennings said. "A lot of it is avoiding pitfalls. You never know exactly what you're going to find until you look in the knee."

Jennings was looking inside Dunahoo's knee by 7:57 a.m. He had her sewn back up in less than an hour.

Aside from its torn ACL, Dunahoo's right knee had no other damage. Last year, Dunahoo's left knee also had a tear in the meniscus, which makes for a more complicated procedure.

Twenty minutes before Jennings made his first incision, Dunahoo was anesthetized. Her body was totally covered with sheets and blankets except for her right leg, which had a tourniquet wrapped tight around its thigh.

Dunahoo's face was covered with plastic. Her eyes were taped shut. She had a tube in her mouth to help her breath.

She had drugs in her body to keep her asleep, other drugs to numb the pain, and still more drugs to fight off the nausea that the pain-killers might bring on. The constant beep that filled the room told everybody that Dunahoo was doing just fine.

The entire surgery was set to the blues, which played through a stereo against the wall.

The entire surgery was set to the blues, which played through a stereo against the wall.

Surgical technicians scrubbed Dunahoo's right leg clean and then wrapped it in a sterilizing betadine-treated plastic sleeve. She was ready for surgery.

Slice, scrape, drill

The entire ACL reconstruction can be done through one incision several inches long beneath the kneecap.

First, the central third of the patient's patellar tendon is harvested. That is what is used to replace the torn ACL.

The work area -- the inside of the patient's knee -- is then cleared of debris. The damaged ACL, and excess tissue fiber and cartilage, are scraped and burned away.

Then, holes are drilled in the tibia and femur bones. Those holes later house the reconstructed tendon, which is held in place with bioabsorbable screws.

The harvesting of the patellar tendon -- which involves tools that look, and sound, like everyday hand drills, hammers and chisels -- can get bloody, even with the tourniquet. Tiny bits of body go flying.

Once the slice of Dunahoo's tendon was removed, it was placed on a sterile table behind Jennings and looked similar to a chunk of fat that might end up on your butcher's floor.

Jennings conducted a good portion of the remainder of the procedure looking at a TV screen. Cameras at the end of his tools showed what he was doing and where he was doing it. With the room dark, the light at the end of the camera made Dunahoo's knee glow like a Christmas bulb.

"Here's the meniscus," Jennings said. "That's the torn ACL right there. There's another stump over there."

To the untrained eye, the images on the screen could just as well have been coming from a far-off planet or deep beneath the sea.

Much of what Jennings does, in fact, is underwater. Saline constantly pumps through the patient's body to irrigate the surgery area. At times, the clear liquid squirted out of the hole in Dunahoo's knee.

By the end of the surgery, Jennings was standing in a pink puddle on the floor. The room smelled of blood.

By the end of the surgery, Jennings was standing in a pink puddle on the floor. The room smelled of blood.

"That's why we wear waders," Jennings said.

Most of the workers in the surgery room wore plastic boots. Masks that cover noses and mouths are mandatory. You learn to recognize people by their eyes.

The insertion of the new tendon was ingenious. The harvested patellar tendon was tied to the end of a thin metal rod. The rod was inserted upward through the holes drilled in the tibia and femur. The rod was then pulled through a tiny hole in the bottom of Dunahoo's thigh, leaving the tendon in its new place.

It was like restringing a pair of sweatpants.

The entire surgery was complete in 53 minutes. Then the surgery room was wiped clean, and Jennings was off to do another operation.

"Hey Megan, open your eyes," anesthesiologist Bil Ragen said. "The operation is over with. You did real well."

Yes, the operation was over, but Dunahoo's struggle to strengthen her reconstructed leg was just beginning.

"She's a hard worker," Emory said while his daughter slept at the surgery center (that's what she did most of Monday). "She'll do everything she needs to do to get back."

And, sure enough, Dunahoo started her painful rehabilitation Wednesday at Pro Therapy in Oakwood while her mother Elaine looked on. Dunahoo wants to be better in time to play soccer this summer.

"I'm ready for the rehab," Dunahoo said. "I don't want to just sit here."

First thing's first, though. Dunahoo -- now with a scar on her right knee to match the one on her left -- must learn how to walk again.

February 7, 2002

Cheerleading: Three cheers for 'good facials'

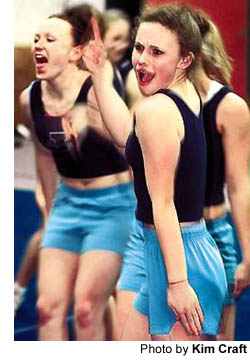

There was so much enthusiasm in the gym, I was surprised there was room for anything else. The Johnson High cheerleaders may be small, but their sound is decidedly big.

There was so much enthusiasm in the gym, I was surprised there was room for anything else. The Johnson High cheerleaders may be small, but their sound is decidedly big.

From the moment the Knights opened their collective mouth, they owned the room. They controlled everything inside of it. Including me.

Mighty blue and white! Get up off your feet!

OK. Sure. Whatever you say. I was blown away.

"That's a lot of spirit," I whispered to Johnson coach Karen Ellis.

"That's what we're shooting for," Ellis whispered back.

This was last Wednesday in Johnson's stuffy auxiliary gym, three days before the Knights were scheduled to compete for a state championship down in Columbus.

Johnson has long been considered one of Georgia's top competitive cheerleading schools, but has yet to win the state's top prize. The Knights have finished second in their classification seven times in the past nine years.

There was no second-place finish for Johnson on Saturday. Unfortunately, no first-place finish, either. The Knights placed third in Class AAA, 11 points behind state champion South Forsyth, the team that placed second to the Knights in the Region 7-AAA tournament the week before.

But last Wednesday, the Johnson cheerleaders filled their practice gym with high hopes. Their post-practice task of teaching a newspaper reporter how to do a side-hurdler jump likely seemed just as daunting as chasing after an elusive state title.

The Knights tumbled and jumped and cheered their way through practice while Johnson wrestlers trained in the distance. They were simply two sports teams preparing for the playoffs.

Just another sport. At Johnson, that's how competitive cheerleading was considered long before the Georgia High School Association began recognizing it as such in 1994. The Knights won three state championships in the Georgia Athletic Coaches Association prior to that.

Just another sport. At Johnson, that's how competitive cheerleading was considered long before the Georgia High School Association began recognizing it as such in 1994. The Knights won three state championships in the Georgia Athletic Coaches Association prior to that.

"At our school, our kids know we work hard," said Ellis, Johnson's coach since 1977. "Our faculty knows we work hard. The other athletic teams know we work hard. And we have respect here. At some schools, they're not as competitive as we are. And that's OK."

The Knights look like a sports team. They embody none of the "hair spray and hoop earrings" stereotype that tends to follow cheerleading around.

When I walked into the gym, they were doing push-ups.

"I was a cheerleader when cheerleading was just put on your little skirt and go out there," said Ellis, who went to Waycross High in the 1960s. "Cheerleading has changed tremendously. I've just learned along with it."

Yes, the Knights cheerleaders still lead cheers for Johnson's football and basketball teams, but their season is really geared toward the competition season that begins in December.

Johnson's 14-member team was whittled down from an original pool of more than 35 at tryouts in August. That's when they started piecing together the two-and-a-half-minute routine they would take to the tournaments.

It's a combination of gymnastics, dance and showmanship, all set to music. And they've been through it hundreds of times. Over and over again. It's got to be perfect.

You see, there are no second downs in competitive cheerleading, no next at-bat to redeem yourself. It's one shot and done, and hope the judges like you. That's a lot of pressure, and a lot of practice.

"Yeah, you kind of get tired of the music," said senior captain Rachel Burke. "But we could sing the whole thing because we know it by heart. We've heard it so many times."

Somehow, Burke and her crew manage to exhibit the enthusiasm of first-timers on each and every run through the routine.

"We really stress that more than other schools do, the energy and the excitement," Burke said. "I think that's what makes us so different. You have to put everything into it every time, all of your heart into it every time. Because otherwise it doesn't have that Johnson look."

And that "Johnson look" can be seen just as easily from the back row as the front. Expressions are exaggerated. Eyes and mouths open wide. Ponytails go flying, emphasizing every phrase.

And that "Johnson look" can be seen just as easily from the back row as the front. Expressions are exaggerated. Eyes and mouths open wide. Ponytails go flying, emphasizing every phrase.

Imagine the faces you make when you talk to a baby. On the judges' scoring sheets, these are called "Good Facials."

After practice, I asked sophomore Jennifer Cao whether her face gets sore from all the smiling.

"Yeah," Cao responded with yet another smile. "Sometimes our cheeks kind of tingle."

That's right, we're number one! Hold on to your seats, we've only just begun!

On the Knights' final run-through of their routine, they hit it almost perfectly. And they were out of breath."Very good y'all," Ellis said. "That's the best it's been."

Then came the hard part of practice. Teaching me.

"Do I have to do the expressions?" I asked.

"That's the most important part," Ellis replied with a chuckle.

So the Johnson cheerleaders taught me some of the basics. And the basics, I believe, were all I could be taught.There were the jumps: the tuck, the side-hurdler and the toe-touch (which was more of a "toe-reach" after I got done with it).

I butchered some of the dance routine before I moved on to the "stunts," which basically involved me lifting Cao up in the air (granted, she weighs less than 85 pounds).

I'm not sure whether judges would have classified my grimaces as "Good Facials" or not. But after each one of my awkward attempts at being a cheerleader, the real cheerleaders clapped and laughed.

Well, mostly they just laughed.